I would question what metrics would lead to such a conclusion. Consider, for example, the crucially important matter of cost and affordability. That super-tall bar over at the extreme right – that’s US per-capita health care cost compared to the rest of the world:

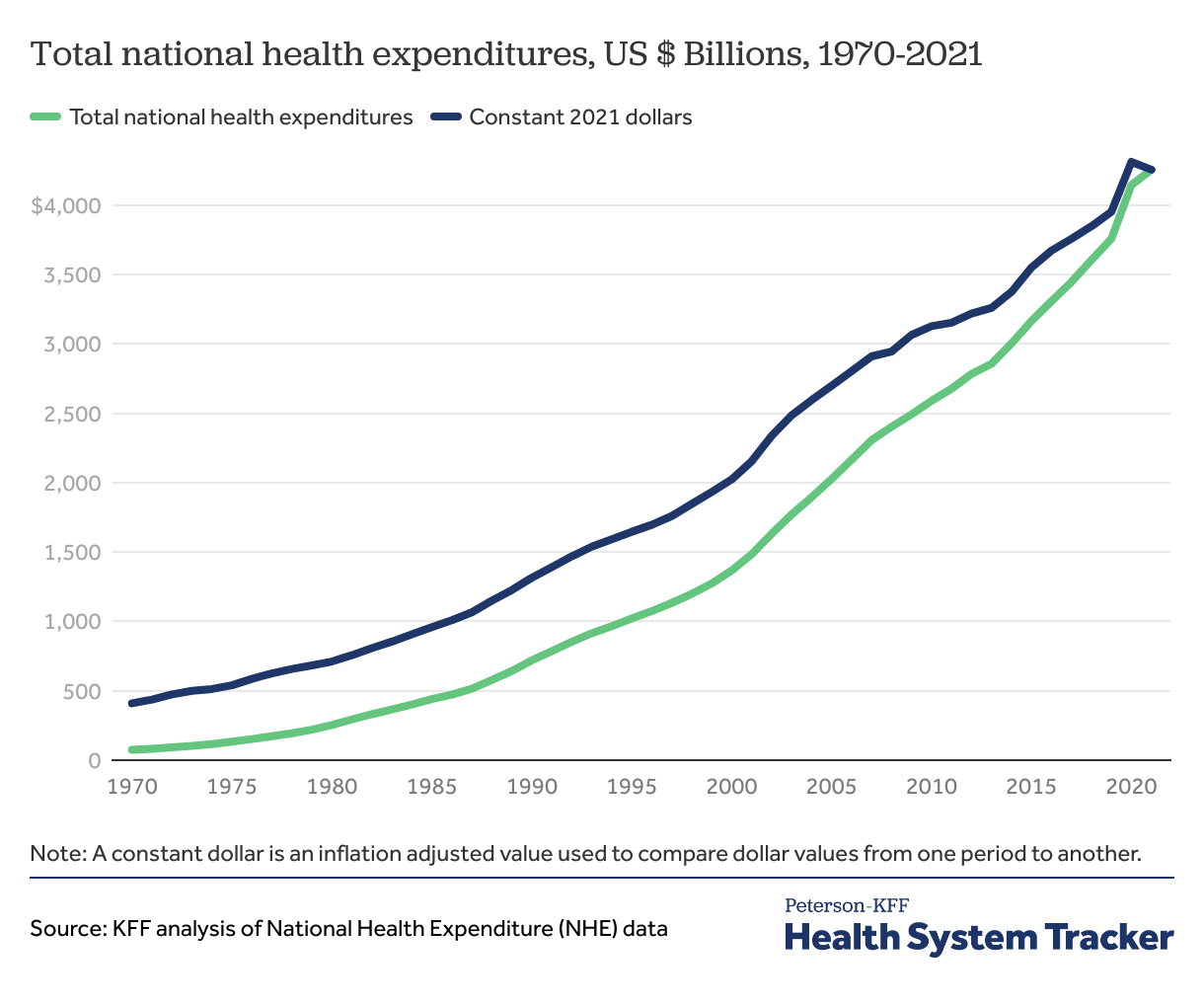

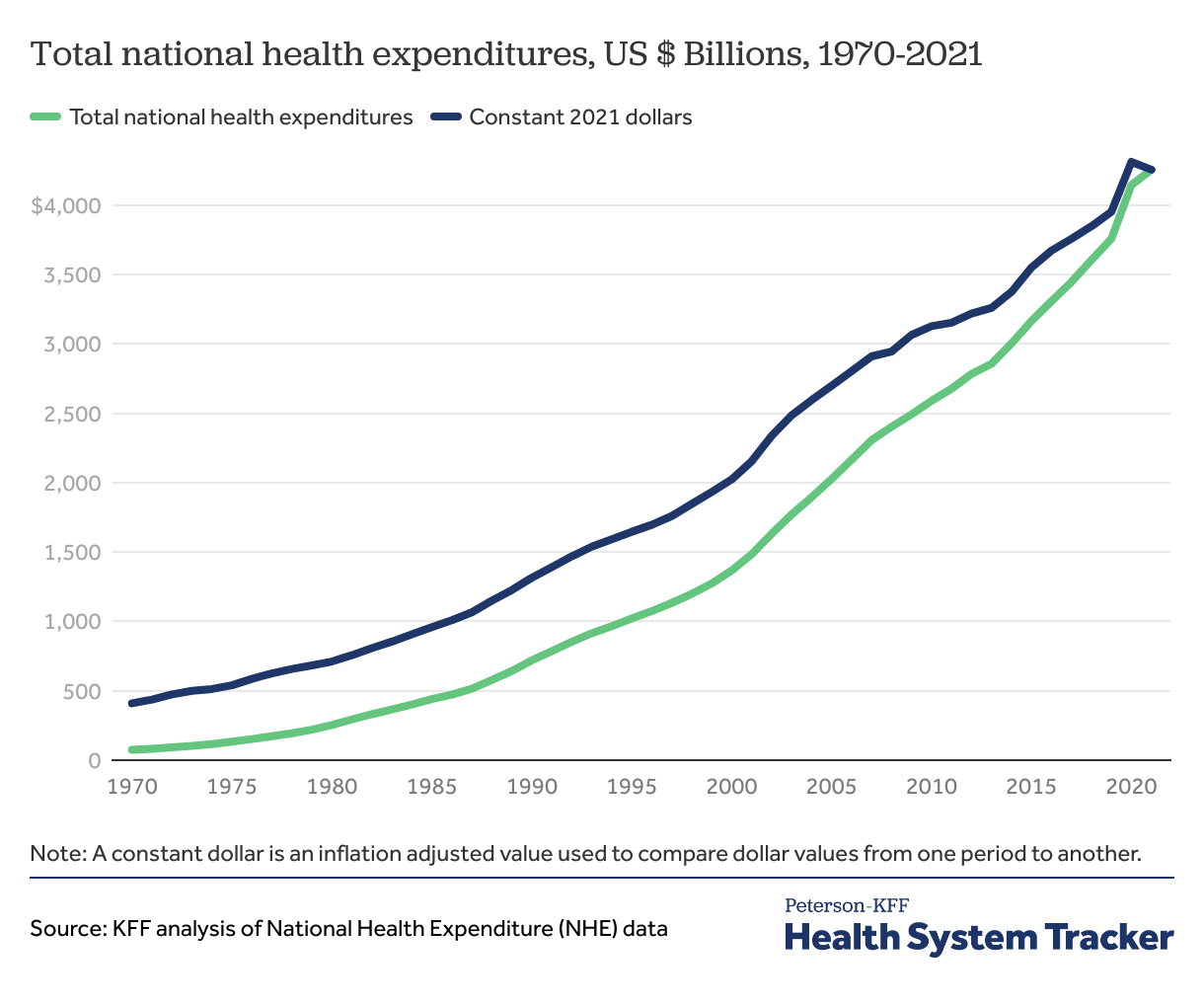

If you look at overall trends, cost growth continues unabated. The small downtick in the inflation-adjusted cost around 2020-2021 is attributed to decreased/delayed utilization due to the pandemic:

From the same source as the above graph:

The U.S. continues to have the highest health spending per capita among comparable countries. In 2021, the U.S.’s $12,914 per capita health spending was more than double the average for other comparably large and wealthy countries ($6,003). The country spending the second highest amount on health per capita was Germany, at $7,383.

As of second quarter 2022, health spending in the U.S. has rebounded since the beginning of the pandemic and spending on health services is growing at pre-pandemic levels.

The state of the U.S. health system in 2022 and the outlook for 2023 - Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker

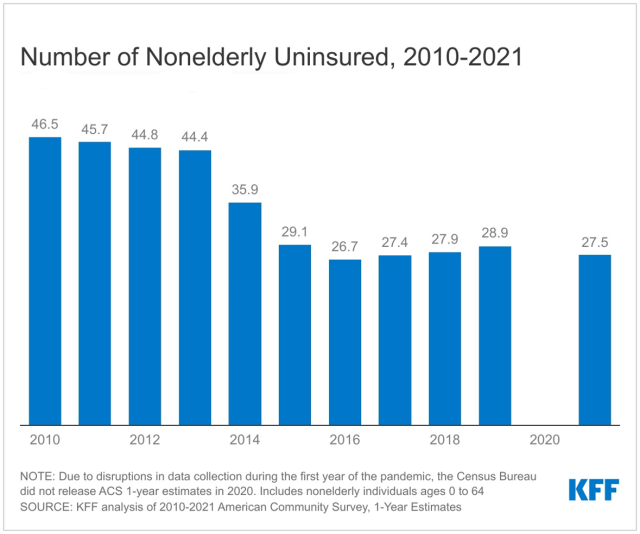

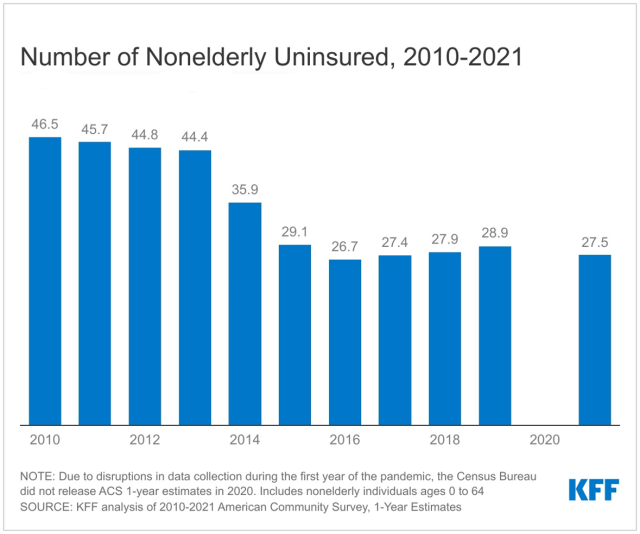

If you look at the uninsured rate, the ACA has indeed had an impact:

Does that mean that “the Affordable Care Act got us about halfway to where we need to be”? With all due respect to Obama’s signature accomplishment, it’s hard to see this.

How are you going to deal with the remaining 28 million uninsured? What sort of additional Rube Goldberg-like costly patchwork might be necessary to fix this? A public option would be a welcome advance, but it won’t eliminate structural problems any more than Medicare did. Structural problems like the incessant intrusion of private insurers between doctor and patient and their involvement in clinical decision-making.* Structural problems like the complete absence of a uniform, rationalized common fee schedule applicable across the entire medical profession. Structural problems like risk-rated premiums (whether rated by individual or by group demographics) and claims denials.

And ALL of those structural problems are playing out against a background of persistently rising costs that outpace inflation and that throw open the whole question of long-term affordability. And those rapidly rising costs will continue due to the dual problems of (a) no one in a position to control them, and (b) the high costs of dealing with a private-insurance funding model.

Furthermore, some of the most powerful lobbies in Washington will strenuously oppose the necessary reforms. The insurance lobby will pull all the stops to oppose any sort of public option, as they did during the formative stages of the ACA, because they see it as a stepping-stone to widespread public health insurance, which they’d never be able to compete with. And the medical lobby will pull all the stops to oppose any sort of fee regulation, even if you show them that they’ll make the same or even more money with lower fees due to much lower overhead and guaranteed reimbursement, because they’ve been brainwashed by the insurance lobby and by right-wing ideology to believe the delusion that a public insurance option implies government “oppression”, whereas they’ve actually been oppressed and financially shafted by private health insurers since forever.

* - I’ve given you cites for this pervasive insurance meddling in the doctor-patient relationship. You don’t seem to have acknowledged them and I’m not sure if you’ve even read them. It’s a fundamental problem intrinsic to the nature of health insurance. Here’s Dr. Jack Resneck, the current president of the AMA, in an AMA Update speech in 2022, commenting on just one small aspect of that much broader phenomenon, just the one aspect of insurance pre-approvals for medication – but it applies even more for general treatments across the board, where not only are pre-approvals often required, but the most beneficial treatment options may be denied altogether in favour of cheaper ones:

[Pre-approval] has become an enormous burden in my own practice, as it has for my colleagues in every specialty around the country. And it’s not just that it’s a costly burden for practices, and it’s driving burnout among physicians and making us hire way more staff than we would otherwise need, just to fill out all this paperwork.

:

But it’s actually affecting our patients, who sit down with us in exam room. We talk about what’s wrong. We figured out a diagnosis. We come up with a treatment plan that we think is going to work. And then the patient gets to the pharmacy, only to find out that their health plan has that treatment listed as requiring prior authorization, which means their doctor now has to spend days and days, sometimes weeks, filling out paper forms and putting them in fax machines.

And then those get rejected and then having to do appeals, where you call somebody, oftentimes a non-physician, a nurse or somebody else on the other end to do what’s called a peer-to-peer appeal, to explain this patient’s condition and why they need this medication.

![]()