The Roman slaves (among others) apparently had the right to buy their freedom, implying they had the right to their own possessions and to accumulate money, etc. Of course, there were always a variety of situations. I assume this didn’t apply to the workers in the proverbial salt mines. There were educated Greeks who ended up slaves, but were able to serve as tutors for the master’s children.

Be really careful with that pie chart.

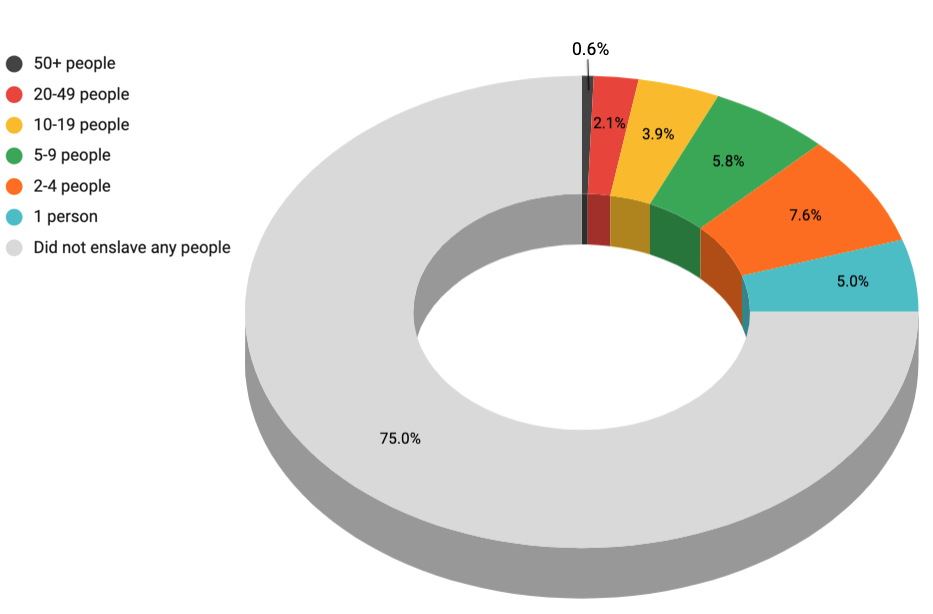

The reason I mention this is that the denominator - assuming it is “total population of the slave states” - can be a bit deceiving. Very few women held anyone as slaves - legal ownership of any property, the enslaved included, was basically denied to married women, and few unmarried women had enough wealth to hold someone as a slave. Furthermore, many plantation households of the time were multigenerational, and sons of the planting patriarch often lived and worked out of the home before heading out on their own - benefiting greatly from those held in slavery by others.

So a lot of folks had a direct benefit from enslaved persons held by someone related to them. Probably close to half the population of the slave states were in that category. Also, slaveholding among the yeoman class would often vary year to year or even season to season. Slaveholding as a percentage of that class would almost double if you counted those who had held someone enslaved over the previous five years, and go up even more for those who hired an enslaved person for a certain amount of time.

I emphasize this because many neo-Lost Causers will trot out a graph like what you showed and claim that it proves the Confederacy did not secede to protect property in slaves, because a system that benefitted so few would not have aroused the passions required for such a step. I know that wasn’t the point of your post, but I thought it should be commented upon.

As DrDeth pointed out, the vast majority of those enslaved worked in agriculture on large cotton plantations. (The median slaveholder held perhaps a half-dozen slaves; the average enslaved person lived on a plantation with 80 to a hundred others.)

Chronos brings up a good point that there was no notion in the antebellum era of any general legal way for a slave to be entitled to be manumitted - indeed, at times some states prohibited manumission or forced those freed to leave the state. Some holders of skilled slaves may have dangled the opportunity for freedom as a way of encouraging greater productivity during the enslaved’s most productive years; there is one case study in Embattled Freedom: Journeys Through The Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps of a married couple who had accumulated a great deal of specie currency in a strongbox as a result of being allowed to hire themselves out by their slaveholder; said slaveholder offered to take money for their freedom at a later date. (The couple self-emancipate to Fort Monroe early in the war; they open a store to sell to Union soldiers, but it ends up being looted and sacked by some of those same soldiers.)

And finally, to bring this back to the point of the @Drum_God 's OP, I recently read Leon Litwack’s Been In The Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery which is a bit dated (published 1979) but is still generally regarded as the top text for its topic. Litwack has an entire section on naming that I just reskimmed; it’s mostly geared toward how freedmen decided on surnames. He does mention in a closing paragraph that some whilte were “left… in utter dismay” at their names being used by those they had held as in slavery, but nothing about any whites who changed their names as a result. If it ever happened, I would guess it was a very rare occurence, and probably difficult to distinguish at this remove from the variable spelling of the 19th century that @hibernicus alluded to in their post.

I can think of some far more likely reasons a defeated participant in a bloody conflict might change their name in the aftermath.

Yes, but assuming it’s accurate as far as it goes, and assuming that ownership in a large plantation rested solely with the titular deed holder - it gives a rough example of the distribution. As long as the owner’s son, for example, wasn’t listed as owning a few of the slaves, then in a large agricultural enterprise, there is one owner.

So - 6.7% had 10+ slaves, 17.2% had 1-9 slaves. This shows that for every 3 people with maybe a small enterprise or as household “servants” there was one person with a fairly large contingent of slaves. Worse yet, considering as you state that generally these statistics mean that 76% counts wives, dependants, and others (in the days of big families) Let’s say half those 76% lived in a household where someone else owned the slave(s). In fact, that’s a serious underestimate, since it’s unlikely the average white household was only 2 people. But even using that number of 2 per household, 23.8/50 or 47.6% of white households owned at least 1 slave. 13% or 1 in 8 owned a substantial number.

Keeping in mind that the elite drive the politics of a region, and this elite made their money by use of slaves, and Lincoln and his fellow abolitionists were intent on changing that - I agree, of course the Civil War was all about slavery. The substantial percentage with less than 10 slaves, at risk of losing a few “unpaid workers” or cost-free domestic help would also be more likely to sympathize with the pro-slavery side too.

There are plenty of stories of slaves, particularly domestic ones, promised their freedom in the future (i.e. when the owner dies) only to have that promise broken when the time came. Thus, demonstrating owners’ prioritizing finances over humanity.

Yes - for example, everything I read about, say, Jefferson or Washington suggests they treated the slaves they inherited from their wife’s family as their own.

The chart was used solely to show that not only was it possible to own a slave when you didn’t have a large plantation, but it was pretty common. It was a reply to someone who asked if it ever happened. And this is Factual Questions, so I provided data.

In what way was I using it recklessly?!

I don’t appreciate your implication. I think you should be really careful with your “concern”.

I wasn’t implying anything about you, the poster - I specifically said you weren’t putting it up to prove a Lost Cause point - but rather about others who might see it and draw from it something more from it.

Is there something you are implying by putting concern (a word I didn’t have in my post, by the way) in quotes?

I am sorry to say that I cannot locate the original Facebook post that sparked this discussion. IIRC, the poster was an African-American woman. I believe the point she was making was that, at the time, some white folks were so racist that they would change their family names in order not to be associated with a family of Black people who appropriated the name. I found the post to be questionable because, as was pointed out above, I find it unlikely that an aristocratic former slave-owning family would want to change something as fundamental as their family name. I thought that the most likely explanation was that, in an era of widespread illiteracy, spelling of names (or anything else, really) was not as standardized as we think of it today.

I do not believe there was any intention to claim that people who use names like Smyth or Clarke today do so for racist reasons.

Yes, you implied that I was being reckless in providing raw data to answer a question. Therefore, the concern was in scare quotes.

If you aren’t trying to accuse someone of being reckless on a sensitive manner, don’t lecture them about being careful.

And my post was trying to keep things in a neutral, factual manner as befits this forum. It was not my intention to get into the political implications of the subject because this isn’t the right place for it. And I don’t appreciate someone trying to drag me into such a discussion here either.

[Moderating]

Let’s assume best intentions from other posters, please. If there’s a way to interpret something someone said as an attack, and there’s a way to interpret it as not an attack, it’s more conducive to discussion to take the latter interpretation, especially when that person says that that was their intention.

Yeah sorry, and I apologized to SunUp in PMs already.

Some Roman slaves. Lots of slaves were worked to death with no reprieve or rights, whether mine slaves or some of the agricultural slaves. Or forced into sex work or fighting to the death.

It’s not the full picture to be looking at the house slaves and saying that was Roman slavery, or Roman slavery was better than Southern US slavery. A lot of Roman slavery was just as brutal.

Some Roman slaves. Servi poenae did not have that right.

And even some “freed” slaves were anything but.

According to the PBS article:

Roman owners freed their slaves in considerable numbers: some freed them outright, while others allowed them to buy their own freedom. The prospect of possible freedom through manumission encouraged most slaves to be obedient and hard working.

Doesn’t counter a single thing I wrote.

To be fair, you did not post raw data. You posted a piechart that provides no reference to where the underlying data came from.

I guess you missed the link right before it…?

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/ushistory1os2xmaster/chapter/wealth-and-culture-in-the-south/

Here is the reference in that link:

- US History. Authored by: P. Scott Corbett, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. Provided by: OpenStax College. Located at: OpenStax. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at Ch. 1 Introduction - U.S. History | OpenStax

I mean… ![]()

Yes… So where did they get the data to generate that chart? For all I know they just made it up. Piecharts are notoriously misleading especially when the divisor is not defined.

Beats me. It seems to line up with this chart:

Note that is supposed to represent 1850, 10 years earlier. And the number ranges aren’t the same, so you can’t do a direct comparison. But they don’t vary much. This chart is from:

That pie chart originated from this textbook:

Regardless, the point was that slaves were not exclusively owned by wealthy plantation owners. Quite a number were on small farms.

What you can’t derive from these, of course, is what percentage of slaves were on plantations. Let’s simplify the numbers… Let’s say you have ten farmers, nine of them own one slave, and one owns 100 slaves. Obviously most of the farmers with slaves in that simplified scenario have small farms, but the vast majority of slaves are on a big plantation.

But that’s all irrelevant to the point that it was common for small farms to have slaves in the south prior to the US Civil War. Is that at all in dispute?

I heard a story once that Frederick Douglass got his last name from a poem, which used the name “Douglas” a lot, but added an extra S at the end “to make it different.” Could this be a possible source of the “names are spelled differently” story?

This may be true. He had used his mother’s name of Bailey previously.

Nevertheless, everybody has always agreed that ex-slaves changed their names. The subject is whether ex-slave owners changed their names. This throws no light on that.

The data for Atamasama’s cite probably comes from the U.S. Census - that’s what I’ve seen cited for similar presentations before. Generally, the numbers that cited the census are in agreement with the graphs I’ve seen here.

To retabulate the data would probably take a very deep dive into census returns, probably stored on microfiche at the National Archives.

(After a brief Google search) It looks like the images of the returns are available online, though not in machine-readable form.