I thought The Land, of Stephen R. Donaldson’s Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, was possibly the best thing about those books.

Somtow Sucharitkul’s Mallworld is a shopping mall that occupies an entire world. Kinda like The Mall of America as a cancerous growth.

It inspired the filk song “It’s a Mall World after all.”

The community of the London underground in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere is highly imaginative.

It’s not that impressive a concept, especially now, but I was always impressed by the world-building in Asimov’s Caves of Steel, on Earth specifically, though Solaria and Aurora (in the other books of the series) are interesting too.

Few have topped Hal Clement’s Mesklin in Mission of Gravity.

Mieville’s Bas Lag trilogy is a pretty imaginative world–it’s got a kitchen-sink approach that folks feel strongly about. Amphibians that can sculpt water with their hands, beetle-headed women whose male counterparts are unintelligent insects, vicious magical flying hands, sentient mobile cacti, tame aerial jellyfish employed by police as riot control, advanced body-grafting employed as artistic and horrific penalty for crimes, and more and more and more. It has more ideas in each chapter than most have in a whole book.

Also, his latest (?) book, Railsea, is pretty freakish in a good way: a world in which the “ocean” really consists of myriad train tracks across a flat desert beneath which live leviathan creatures like giant moles. It’s a riff on Moby Dick, as various trainlike contraptions crisscross the tracks hunting their prey.

The Neverending Story has a similar feel: tons of stuff is happening, and the author conveys a consistent sense that the story being told is only one of many different stories happening in the world.

Yep.

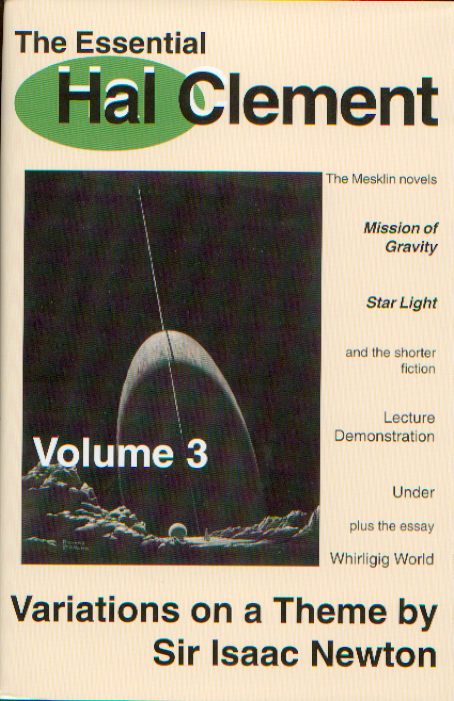

the NESFA press edition of volume III of Clement’s works has a cover image of Mesklin as a very oblate spheroid, as you’d expect. Clement himself observes, in one of the supplementary articles to that volume, that he did a more careful computer simulation much later and concluded that the real shape differed from what he had originally expected. I’m more than a little curious about what that shape would be. a freshman-level physics analysis still gives that oblate sphere, and I’m wondering what new details crop up to spoil that simple picture.

cover of the first edition, which is similar:

And yet, no one linked to Kirby does Lord of Light?

Or his novel Iceworld, set on a planet of unimaginable cold.

Not what I imagined. ![]()

Jack Chalker’s Well World deserves mention.

I rather enjoyed the secret of Lyndon Hardy’s sixth magic. Of course, I was only 14 when I read it, but the sixth magic caught me totally by surprise.

Would also like to second Little Nemo’s Well World from Mr. Chalker as well as his (Chalker’s) flux and anchor.

You just reminded me of this and triggered me throwing some (very small amount of) money at an Amazon independent seller for the whole trilogy.

Robert Silverberg’s Majipoor from Lord Valentine’s Castle and its sequels is an amazingly complex and well-imagined world.

Sounds like the Weiss/Hickman Death Gate cycle

Personally, I like Le Guin’s worldbuilding, both in fantasy (Earthsea) and SF (The Word for World is Forest)

And I love Cherryh’s whole universe, but the non-human parts especially.

And David Brin’s Uplift Univers, love that.

As is Brian Aldiss’ Helliconia trilogy, where whole civilisations rise and fall within the space of a single Great Year as the planet takes 3,000 Earth years to complete one of its own.

More obscure, but also more grandoise: Sucharitkul’s Chronicles of the High Inquest. Very baroque, post-scarcity, high scifi that explores the concept of utopias.

IIRC, Hal’s new calculations still came up with an oblate spheroid, but he had miscalculated just how oblate it had to be.

Considering it was began in 1910, Edgar Rice Burroughs did a great job in his Martian series. The world and its culture was pretty vividly portrayed and very consistent.