Ok, let drill down and consider the consensus among economic theorists regarding gold. I’ll pull some textbooks off my bookshelf. John Cochrane, Asset Pricing 2001: no entry in the index under either “Gold” or “Precious metals”. Bodie, Kane, Marcus (BKM) Investments 1999, ditto. BKM does have references to commodities, though not “Metals”. They discuss futures contracts.

Gold is considered a sideshow, not worth spending too much time on. Portfolio manager David Swensen in Unconventional Success 2005 contrasts core asset classes with non-core asset classes. Gold doesn’t make either list, nor is it listed in the index.

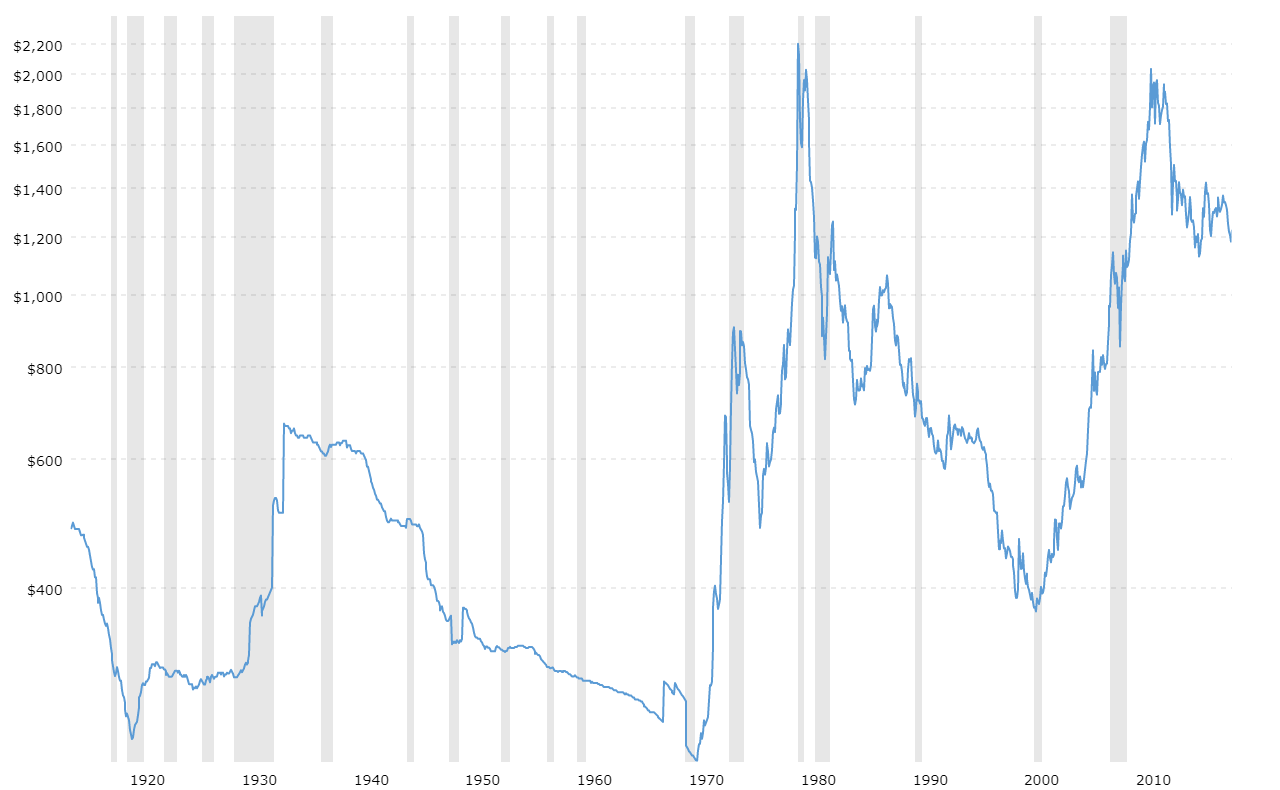

Sharpe et al Investments have an entry on gold in their index. It is listed under Tangible Assets in Appendix A.2 of their last chapter; discussion is less than half a page. They mention that gold isn’t correlated with the stock market, assert that it’s correlated with the CPI (not so sure about this: my linked 2009 paper suggests otherwise), and mention that there are many methods of investing in gold and that silver and other precious metals have similar properties for those interested. Not a rousing endorsement, more like an afterthought.