The reason “calories in / calories out” gets used this way is that there are a million and one excuses used by people who have trouble losing weight. It is an oversimplification, but it is much closer to the truth than the myths repeated by the people who think their thyroid/metabolism/setpoint prevents them from losing weight. While there are a lot of factors determining how fat you are and how a caloric deficit will play out, all of those factors can be overcome by strict adherence to a well-balanced diet with a caloric deficit.

Well, BMI was invented by Adolphe Quetelet , who had no medical experience whatsoever, and it was based upon the avaerage measurements of French & Belgian peasants in 1830 or so, which has little or no meaning in 2014. It even originally cut off at 6’ as few people were tall enough.

Per wiki *“In an analysis of 40 studies involving 250,000 people, patients with coronary artery disease with normal BMIs were at higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease than people whose BMIs put them in the overweight range (BMI 25–29.9)”…The study concluded that “the accuracy of BMI in diagnosing obesity is limited, particularly for individuals in the intermediate BMI ranges, in men and in the elderly. These results may help to explain the unexpected better survival in overweight/mild obese patients.”[22]

A 2010 study that followed 11,000 subjects for up to eight years concluded that BMI is not a good measure for the risk of heart attack, stroke or death. *

Its based upon a too small sample size of people whose lifestyle varied greatly from our today.

And, it isn;t a good measurement of health risks, either.

Never!

{Health myth}~ Frequent meals speeds up metabolism significantly.

Um, no it doesn’t. That’s not to say that small, frequent feedings aren’t conducive to weight loss but just not because you are burning a higher number of calories as a process of metabolism.

Being “quadriplegic” means you can’t move your arms or your legs.

False. Being a quad means all four limbs *suffer from some degree of paralysis *, but many quads have the ability to stand and even walk short distances and have more lower body functionality than some paraplegics. Often times the more severe paralysis is in the arms, hands and fingers.

Isn’t there a better measurement? I have seen waist/height ratio, but I thought there were some other calculations that are even better at determining health risk than BMI.

It was my understanding that subcutaneous fat isn’t really a problem, it is more the visceral fat that contributes to diseases.

I’m disappointed that cracked article didn’t talk about drug dogs. They give false positives 40-80% of the time, and respond to racial disparities (they find more false positives on latinos than on whites).

There is a book I ordered from the library that hasn’t arrived yet: the rise and fall of modern medicine

In it the author claims that the low hanging fruit in medicine has been picked (the public health advances of the 19th and 20th century, the various medical advances from WW2 until about 1980) and since 1980 advances have been more about tweaking and building on existing advances than groundbreaking new advances. He claims that medicine has become obsessed with lifestyle and environmental factors which are not as powerful as are claimed at promoting health. I wonder to what role the obsession with metrics also plays in this. The books ‘overdiagnosed’ and ‘overtreated’ address these problems of obsession with metrics to the point where side effects of medical interventions outweigh the health benefits of intervention (the authors claim treating mild hypertension or mild diabetes can cause more health problems than it prevents, that type of thing).

I think we will have a new generation of medical advances based on human/machine technology interfaces; advances in cell biology and systems biology. And personally I think things like that will lead to a new golden age of medicine in the 21st century (that is my amateur assumption of current trends). However in the meantime obsession with lifestyle and metrics, combined with tweaks in existing technology (rather than groundbreaking new ones) seems to be the norm.

Been reading the reviews on Amazon, sounds like my kind of book.

I read Overdiagnosed, one of my favorite books dealing with health issues. It deserves a thread all on its own, but just have no time to devote to it right now.

Quetelet created a mathematical tool that attempted to fit body shapes (weight relative to height) into a normal distribution. His tool did that fairly well and more or less continued to fit the population roughly into a normal distribution up until recent decades, after which time a slight right skewing of the curve has become a dramatic one.

He made no medical conclusions from that mathematical analysis and no judgements about what was “overweight” or “obese” … he was concerned only about statistical normal, not health ideal.

In modern times it was adapted as a tool to study populations and it was determined that being in the higher ranges of percentiles for BMI correlated with higher health risks (as does being in very low percentiles). Not everyone who is over 30 BMI is overfat (see The Rock) but most are.

The cut-offs for what is called “normal”, what “underweight”, and what “overweight” are indeed out of date and were always a bit arbitrary … that the accumulated data shows that low “normal” have higher mortality rates than low “overweight” … the healthiest outcomes seem to be associated with (depending on the study) either high “normal” BMIs (23 to 25) or even slightly into the “overweight” category (26ish). Over 30 though is and has always been pretty highly correlated with being overfat. Still it really is a tool to study populations and adapting it to classify individuals is something that should be done with more awareness of its limitations than is often done. For individuals a BMI over 30, and less so one much over 25, is one flag that further assessment is needed. Not much more than that. And under 25 should not be a complete all clear. For individuals nutrition and exercise habits matter more than BMI, or even fat percent.

Note that those mortality studies are for complete populations. The study quoted by that wiki article is of those who already have coronary artery disease, and similar results are found for those with diabetes (discussed on these boards previously here)*: it gets labelled “the obesity paradox.” You are less likely to have coronary artery disease or diabetes if you are not obese but given a population of people with those conditions those who have it despite a lack of obesity are likely to die sooner. Maybe that tells us something about the genetics of who gets the disease without obesity. Maybe that they are the “skinny fat”, not with high BMI but still with a high percent of body fat, a very low fat free mass, and who store their fat centrally, or who have low fitness without fatness. So far not completely clear.

The fact that BMIs have changed dramatically for populations tells us information that merely tracking mean weights could not. And while a hypothesis that populations have in recent times become much more muscular with many more people lifting weights and bodybuilding to levels that correlate with BMIs of over 30, over 35, over 40, and over 45, can be entertained, there is little to support it. The reality is that the population wide increases in BMI, the tremendous growth of the obesity to morbidly obese BMI groupings, is because many more are overfat.

Wesley maybe the better measurement is the ABSI, as we have previously discussed here?

My hope is also that we are entering a new era of progress in medicine fueled by a confluence of aligned incentives for Accountable Care Organizations (rewarding better health outcomes across populations) and soon to come and emerging real time and trended health data collection as the Fitbit type stuff grows up and integrates into electronic heath data systems (which piggybacks on your prediction some) … allowing automated flagging of worsening of status in higher risk patients before they would ever come in for a recheck and thereby intervening before things get worse.

*This post in that thread, now that I look it over, recaps most of these points in a more organized fashion than I did today.

In a sense weight loss itself is kind of a myth in that most people really overestimate the success rate for losing weight and keeping it off. Any time they do a study following a cohort of people who managed to lose weight, a large proportion of them either gain it back within 5 years, or bounce between their former weight and healthy within that time.

And that goes hand in hand with the myth that it takes equal effort to be a particular bodyweight. Sure, you might be comfortable at 80kg, but a person who’s recently dieted down to that weight may feel incredibly hungry all the time.

(I’ve no axe to grind on this: I’m in good shape and pretty much always have been.

But I know a large part of that is I’ve always had manageable appetite levels. Heck, I sometimes forget to have a meal, and not realize until the next mealtime).

An absence of overweight is not proof of good health.

But it’s circumstantial evidence, which has some value anywhere except in a court of law.

The problem is people like to conflate the difficulty of achieving long-term weight loss (a true thing) with disproof of the calories in/out model (which is also a true thing). In fact, there is no contradiction between the difficulty people have in controlling their diet and the truth of the calories model.

Truth. One of the real problems with the discourse on dieting is that we can only speak about willpower in metaphorical terms. We don’t (yet) have a science of willpower, and so we’re left to talk about it like it was talked about two thousand years ago. Willpower, just like metabolism, is a physical phenomenon, but we don’t really know its inputs or factors, and we cannot easily compare between people how hard it is to will a certain task. The fact that we cannot even really describe it much less understand it scientifically is what causes a lot of problems when we talk about weight loss.

[lawyer hat] That’s a myth, actually. Most cases are proven using circumstantial evidence. [/lawyer hat].

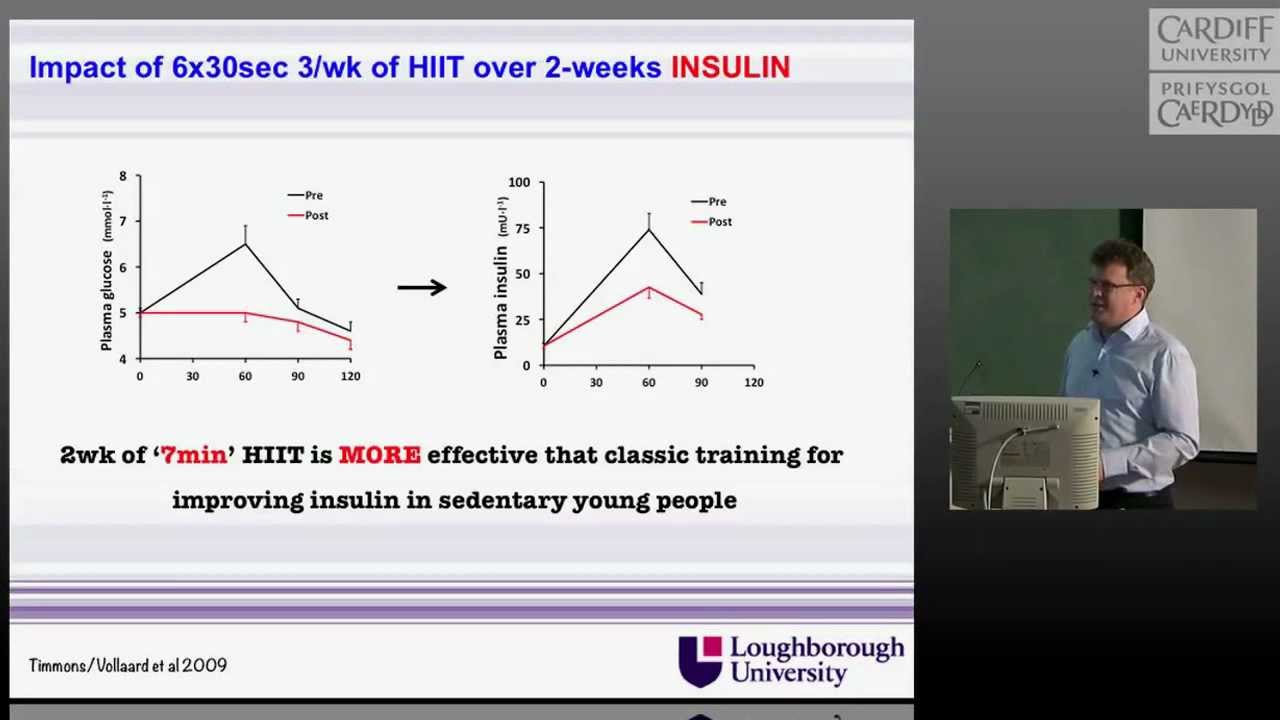

There certainly is reason to believe that. As Dr. James Timmons explains in the video below, every exercise training study has identified low responders and/or adverse responders. Roughly 10% of subject are adverse responders.

Also note that Timmons states that there are absolutely no supervised exercise-only intervention studies that have tracked disease prevention. Not one.

Sorry to be time constrained but I do not watch linked videos very often.

I would be shocked to learn that for any sort of activity there are not genetically impacted upper limits, be they strength, speed, power, endurance, reflex speed, or whatever. Can you share what is meant by “adverse responders” though? He claims that every sort of exercise has 10% of people who respond being worse off than they were if they did no exercise and that every study has shown that? That is clearly untrue.

In terms of the second claim, also untrue as the briefest of searches shows: among those with impaired glucose tolerance at baseline development into diabetes was reduced by 46% with exercise only (significantly more than by diet only and not significantly different than the diet plus exercise arm). Easy to go on with randomized controlled trial meta-analyses regardinghypertension and on on but the claim is already falsified.

Re-read my post. Timmons there are no supervised exercise-only intervention studies. Your linked study covers both diet and exercise.

Yes. Read it. There was an exercise only arm. Compared to control and diet only it was superior.

What part of that do you not understand?

Missed that. Sorry.