THE BIRD WOMAN

“Perhaps she won’t be there,” said Michael.

“Yes, she will,” said Jane. “She’s always there for ever and ever.”

They were walking up Ludgate Hill on the way to pay a visit to Mr Banks in the City. For he had said that morning to Mrs Banks:

“My dear, if it doesn’t rain I think Jane and Michael might call for me at the Office today – that is, if you are agreeable. I have a feeling I should like to be taken to Tea and Shortbread Fingers and it’s not often I have a Treat.”

And Mrs Banks had said she would think about it.

But all day long, though Jane and Michael had watched her anxiously, she had not seemed to be thinking about it at all. From the things she said, she was thinking about the Laundry Bill and Michael’s new overcoat and where was Aunt Flossie’s address, and why did that wretched Mrs Jackson ask her to tea on the second Thursday of the month when she knew that was the very day Mrs Banks had to go to the Dentist’s?

Suddenly, when they felt quite sure she would never think about Mr Banks’ treat, she said:

“Now, children, don’t stand staring at me like that. Get your things on. You are going to the City to have tea with your Father. Had you forgotten?”

As if they could have forgotten! For it was not as though it were only the Tea that mattered. There was also the Bird Woman, and she herself was the best of all Treats.

That is why they were walking up Ludgate Hill and feeling very excited.

Mary Poppins walked between them, wearing her new hat and looking very distinguished. Every now and then she would look into the shop window just to make sure the hat was still there and that the pink roses on it had not turned into common flowers like marigolds.

Every time she stopped to make sure, Jane and Michael would sigh, but they did not dare say anything for fear she would spend even longer looking at herself in the windows, and turning this way and that to see which attitude was the most becoming.

But at last they came to St Paul’s Cathedral, which was built a long time ago by a man with a bird’s name. Wren it was, but he was no relation to Jenny. That is why so many birds live near Sir Christopher Wren’s Cathedral, which also belongs to St Paul, and that is why the Bird Woman lives there, too.

“There she is!” cried Michael suddenly, and he danced on his toes with excitement.

“Don’t point,” said Mary Poppins, giving a last glance at the pink roses in the window of a carpet shop.

“She’s saying it! She’s saying it!” cried Jane, holding tight to herself for fear she would break in two with delight.

And she was saying it. The Bird Woman was there and she was saying it.

“Feed the Birds, Tuppence a Bag! Feed the Birds, Tuppence a Bag! Feed the Birds, Feed the Birds, Tuppence a Bag, Tuppence a Bag!” Over and over again, the same thing, in a high chanting voice that made the words seem like a song.

And as she said it she held out little bags of breadcrumbs to the passers-by.

All round her flew the birds, circling and leaping and swooping and rising. Mary Poppins always called them “sparrers” because, she said conceitedly, all birds were alike to her. But Jane and Michael knew that they were not sparrows, but doves and pigeons. There were fussy and chatty grey doves like Grandmothers; and brown, rough-voiced pigeons like Uncles; and greeny, cackling, no-I’ve-no-money-today pigeons like Fathers. And the silly, anxious, soft blue doves were like Mothers. That’s what Jane and Michael thought, anyway.

They flew round and round the head of the Bird Woman as the children approached, and then, as though to tease her, they suddenly rushed away through the air and sat on the top of St Paul’s, laughing and turning their heads away and pretending they didn’t know her.

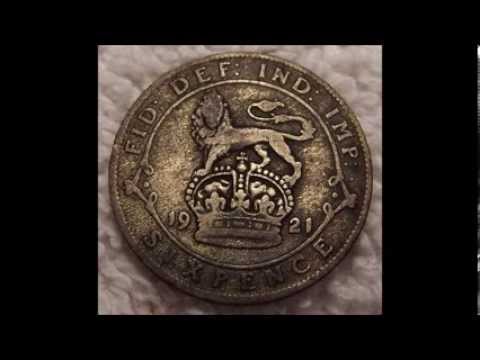

It was Michael’s turn to buy a bag. Jane had bought one last time. He walked up to the Bird Woman and held out four halfpennies.

“Feed the Birds, Tuppence a Bag!” said the Bird Woman, as she put a bag of crumbs into his hand and tucked the money away into the folds of her huge black skirt.

“Why don’t you have penny bags?” said Michael. “Then I could buy two.”

“Feed the Birds, Tuppence a Bag!” said the Bird Woman, and Michael knew it was no good asking her any more questions. He and Jane had often tried, but all she could say, and all she had ever been able to say, was, “Feed the Birds, Tuppence a Bag!” Just as a cuckoo can only say “Cuckoo,” no matter what questions you ask him.

![]()