I hate the hypocrisy of environmentalists. They object to every nuclear waste disposal solution then complain there is no place to store nuclear waste.

No hypocrisy. There is no safe place to store nuclear waste on the timescales required for responsible stewardship, not just bury and forget and let the future deal with our mess.

So the answer is to stop making any. Until we learn how to manage it safely, or make very, very little of it compared to current practice.

Let’s not pretend that the “let the future deal with it” is in any way comparable with other forms of pollution, whether CO2 or otherwise.

CO2 being released now is already affecting us, and will have even worse effects in the coming decades. “The future” is, at most, the children of people living now.

Yucca Mountain, on the other hand, is being held to limits a million years out. A million! We won’t even be homo sapiens then. If we survive at all, the nuclear waste problem will be trivially solvable by them. And they’ll be motivated to do so, not because of the waste, but because radionucleotides are a valuable resource. People will probably want to mine that resource in centuries, not millenia. And if we’re all dead then, who the fuck cares.

It’s just an insane difference in standards and completely nonsensical. Nuclear waste is a solved problem by any reasonable standard.

Although it may be effective with realtively small amounts, from a reactor at the sea, I wouldn’t call “dump it in the ocean” a solution.

Well, yes. Tritrated water in seawater forms a mixture, not a solution.

This is ridiculous. Maybe if we didn’t use any electricity and it was a choice between living a neolithic lifestyle or adopting nuclear power you’d have a point. But you can’t just look at nuclear power in a vacuum; you must compare it to other alternatives.

Pray tell, how are we currently storing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses, which we currently do at a rate of billions of tons a year, in a way that’s showing responsible stewardship on the necessary time scale?

There is no safe place for coal waste either, and it certainly isnt safe to put that CO2 waste (and other pollutants) into the air. Global warming is a crisis= NOW. Nuke waste is something we can solve later, once we know we arent going to drown or melt.

On a scale of bad waste, Coal is a 10, and nuke is far down the scale.

Nuke bros like to pretend that nuclear power is the only viable long run energy source. We don’t know that. The cheapest long run power source will depend on technological evolution and Gen I, Gen II, and Gen III nuclear power has proven itself to be expensive and subject to cost overrun.

What are possible alternatives?

a) Cheap and clean solar and wind with battery storage (tech still evolving, but has a track record of cost improvement, unlike nukes) for overnight, hydrogen storage for longer term.

b) Geothermal energy, using technology developed in the fracking industry. Can be dialed up and down, like gas peakers. Article: Enhanced geothermal power is finally a reality

c) Fusion power, using magnetic confinement encased in an adamantium/unobtainium mesh. Ok, I’m not optimistic on this, despite recent progress.

d) A blend of things, which I’m guessing is where we’ll end up. Plug for small hydro: How to make small hydro more like solar - by David Roberts

Plug for retrofit hydro: of 90,000 dams in the US, only 3% produce power: https: //www.volts.wtf/p/whats-going-on-with-hydropower#details

e) Small modular reactors. Unfortunately, NuScale hasn’t taken the world by storm, at least yet.

What technologies would we expect to get cheaper over time? According to a paper by Abhishek Malhotra of the Indian Institute of Technology and Tobias Schmidt of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, it depends on a) design complexity, and b) need for customization. Here’s the chart:

Nukes are highly complex and highly customized. Mass produced products like LED lamps and solar photovoltaic modules are the opposite. Most other systems are in between. My money is on, “Something outside the upper right corner of this chart.”

I’m sympathetic to keeping existing nukes open though. Hell, I’d like to build new nukes: it’s late in the day and we need to build and support supply chains that will keep our options open.

I don’t believe this is true. There are, in fact, places nuclear waste can be stored essentially forever.

You know what you can’t store safely? Carbon dioxide.

Only if you ignore what is actually being said. Nukes are the only viable alternative today. If we can switch to renewables over the next 30 years, that’s amazing. If we can develop fusion in the next 50, that’s literally as big a deal as the industrial revolution. It’s monumental - it unlocks the stars for us.

The problem is that if we keep burning fossil fuels for the next 30 or 50 years many of us will die. There’s even a chance that society will get banged up badly enough that we fall behind schedule on those renewables or fusion. Maybe enough so that we never get there, because society falls apart and (with all the easily accessible fossil fuels already gone) it can never climb back up to the level it needs to be at to develop fusion or renewables.

We need to drastically cut down fossil fuels, a decade ago. The only way to even approach that is to go all in on nukes until one of these other solutions becomes practical.

Yes, we’re 2 or 3 decades behind schedule. Frustratingly, nukes are not especially viable today. In practice, it takes over 7 years to build a nuclear power plant, and outside of China the requisite supply chains dried up last century. Vogtle construction started in 2009 and came on line last month - 14 years.

You know what’s viable and cheap? Solar. Yes, the last 20% of capacity will be challenging to cover without fossil fuels, but we’re not there yet.

Article length treatment of the above, by economist Noah Smith: Solar is happening. Nuclear is (mostly) not.

It would have been easy if we put in place CO2 taxes or tradable emission permits 30 years ago. If nukes were the best solution, they would have come out on top now. If they weren’t, we’d use whatever did. Then, we’d only have to share the technology with China, India, and the rest of the developing world.

This I will happily agree with. There’s no way fossil fuels would have been so dominant if the extraneous costs had to be borne by the market.

The hanging chads, and GOP fraud prevented us from electing Al Gore back in 2000. We wasted 23 years we could have used to fight carbon and global warming.

I believe France only has three or four design variations. They’re considered highly standardized, but I don’t know if that’s just with respect to other industrial processes or just other nuclear reactors.

So when the topic of global warming comes up, it is neither practical, realistic, or hard-headed to say we just need to go nuclear. It’s sensible to try to keep existing power plants open. As for new nukes, I’m done screwing around: build them. I predict that 20 years hence there will be cheaper paths to net zero when viewed retrospectively. But it’s past time to press hard for efficient solutions: the planet is burning (metaphorically of course).

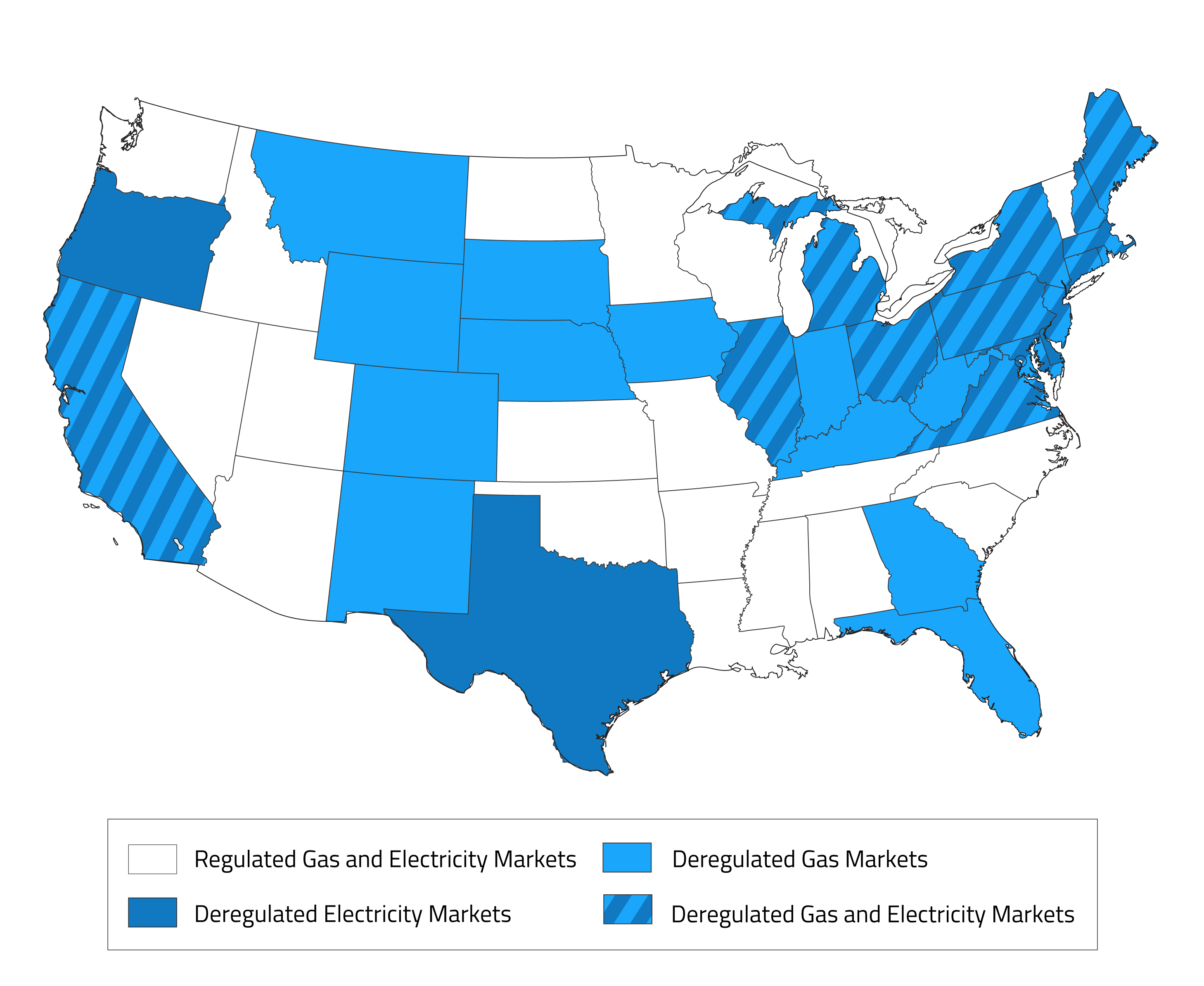

In the US, barriers to large scale Gen III nuke power are not only technological: they are also financial. Deregulated utilities have no interest in them. Deregulated utilities have no interest in them, and states with the highest populations tend to be deregulated. See map (the light blue states have deregulated gas, but not electricity).

Furthermore given the predictable cost overruns in Georgia’s Vogtle units 3 and 4 and the Virgil C. Summer fiasco in South Carolina, it will be very hard to persuade utility commissioners to move forward with another $30 billion plant. As for a massive federal program, well it would be pretty risky considering that annual Inflation Reduction Act subsidies for green power total to $38 billion.

I post a lot of links, usually to substantiate my claims. But the Noah Smith article on nuclear power is worth reading. Here it is again: Solar is happening. Nuclear is (mostly) not.

He’s more pro-nuke than I am; this isn’t a screed:

The French and Canadian experiences with nuclear power are instructive. My takeaway is that you can only get cost-effective nuclear power by building a series of plants with standardized designs. (Though again, cost-effectiveness is a 2nd order issue in 2023.) Nuclear power has a U-shape cost function: early plants are very expensive, then plants get cheaper, then they slowly get more expensive apparently. See the Noah Smith article for the cite regarding reverse learning by doing in nuclear power construction.

Massive numbers of nuclear power plants have gone offline in France, and repairs there are customized: it’s not a matter of swapping out whole pieces of off-the-rack equipment. So while EDF’s overall cost efficiencies are something to celebrate, they are not the sort of modular solution that NuCor is working on. Cite: The 2022 French nuclear outages: Lessons for nuclear energy in Europe – Clean Air Task Force

Here’s another reason to advocate nukes. Sure, solar is cheap now and worth expanding aggressively. But it’s also land intensive. After a certain point the politically easy locations will get taken and permitting will get more difficult. That problem is worse for wind. So expect their cost curves to turn upwards. Nukes in contrast have a relatively contained footprint.

If construction of 4-5 new nuclear T1000 plants commences by 2026 in the US, that would be a major political achievement. That would still be a side show though, relative to what we can do with renewables. And I doubt whether we will get even one.

Wind and agriculture can coexist quite profitably: the wind turbine takes up only a small amount of land and the rest of land is farmed–and the farmer gets more in rent than he would get for crops in that small area. In the rural area where I live this is happening all over.

With regards to solar there are the vast deserts in the Southwest as well as rooftops.

So I don’t see land as a limiting factor. Limiting factors are the grid to move the electricity around as well as the fact that both wind and solar are intermittent–and storage is expensive.

The problem with land use is political, and outside of the US it won’t bite for a while. But if we want to get to net zero, we need to think ahead.

In the US we outsource our environmental policy to the public, by requiring environmental impact statements and encouraging litigation rather than regulation. The fossil fuel industry has learned to navigate this process, but lots of renewable projects are currently waiting approval. Geothermal plants take 7-10 years to build, and are subject to 6 separate NEPA reviews for various governmental agencies:

Brian Potter, Arnab Datta, and Alec Stapp, quoted in another substack article by Noah Smith:

If anything, NEPA likely stifles newer, environmentally-friendly industries more than older incumbents, which have had many years to work the process in their favor. 42% of the Department of Energy’s (DOE) active NEPA projects are related to clean energy, transmission or conservation, while only 15% are related to fossil fuels. Based on available data, offshore wind offers one of the starkest examples: The U.S. has 42 MW of offshore wind production that is operational, 932 MW under construction, and 18,581 MW bogged down in permitting, most of which are waiting on NEPA analyses to be completed. The climate crisis requires a rapid build-out of clean energy infrastructure but current NEPA permitting processes enforce the status quo, benefiting the fossil fuel industry.

Big picture, permit reform advocates appear to want something more like easy-peasy nuclear regulation, where a single regulator runs the show (mostly), rather than the apparently more burdensome process set up in the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). (Easy-peasy: ha ha I kid.)

While there is a strong case for permitting reform in the US, figuring out the proper regulatory structure to replace it is complicated. Noah Smith has a roundup of articles on it, for those who want to take a very deep dive: The big NEPA roundup - by Noah Smith - Noahpinion

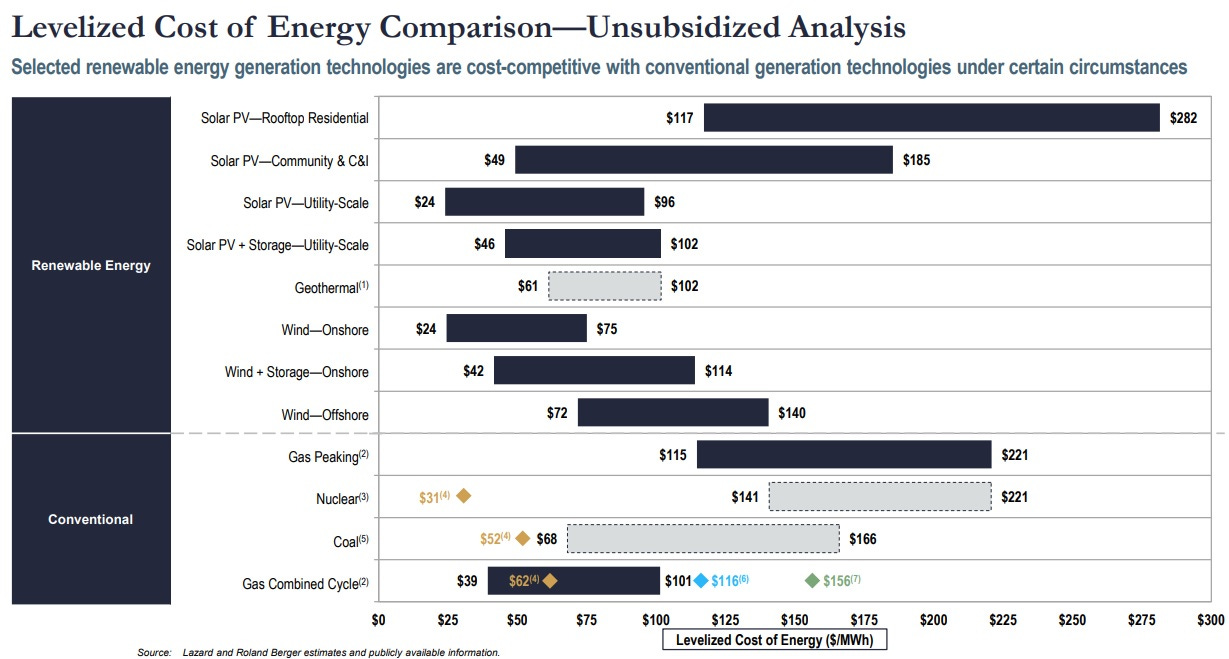

Utility scale solar including storage costs is cheaper than nukes by a wide margin:

The renewable revolution is something to celebrate. From Noah Smith’s latest: Our climate change debates are out of date - by Noah Smith

Together, cheap solar and cheap batteries mean that as of 2023, even without any subsidies, solar power is cheaper than most other ways of generating electricity — even when you factor in energy storage. Natural gas and wind are the only real competitors.

Still to be tackled:

- Seasonal storage, maybe with hydrogen, maybe with new battery technologies,

- In the USA, NIMBYs try to block large scale solar plants,

- Lithium supplies are limited (but so are fossil fuels, and again we’re working on other battery chemistries)

The great thing is that because solar is cheaper, we don’t need politically challenging carbon taxes. True, such policies would promote the energy transition in a lot of ways (eg green concrete, eg electric heating and cooking). But something like that looked like it would ultimately be a requirement 10-30 years ago, and now that might not be the case. We just need to redouble the Green New Deal approach and share battery technologies worldwide.

Thanks to the hard work of millions of technologists and clean energy supporters, the odds of the worst case climate scenarios have declined over the past 10 years. Enablers of human progress chalk up another victory; paranoid parochialists another defeat.

Good to see you post that article. I was already in the process of reading it myself. Its thesis is something I’ve observed numerous times, here and elsewhere–people’s ideas are stuck in the past, often 10-20 years. And in that short time, the economics of renewables and related technologies (like EVs) have totally flipped.

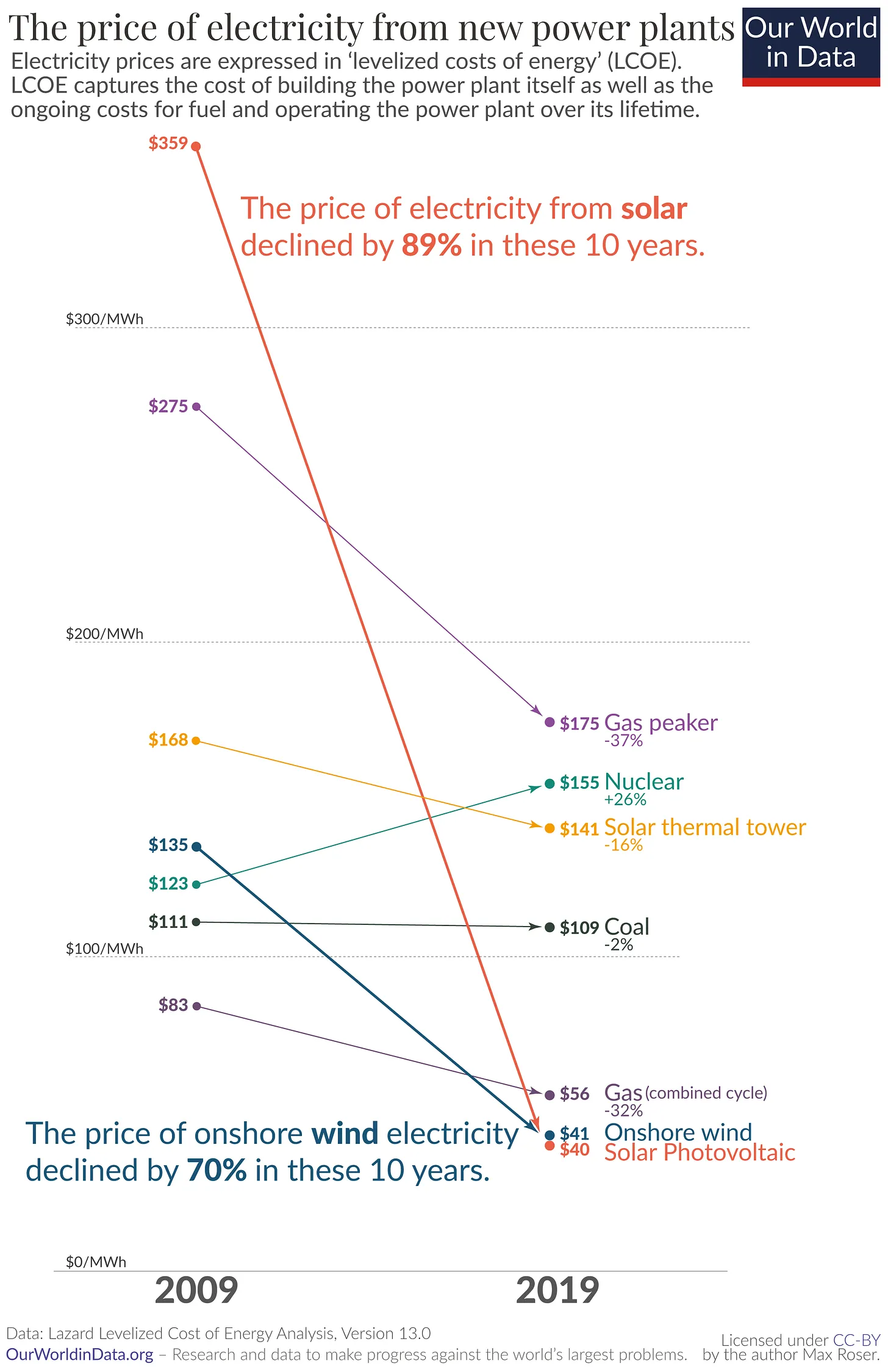

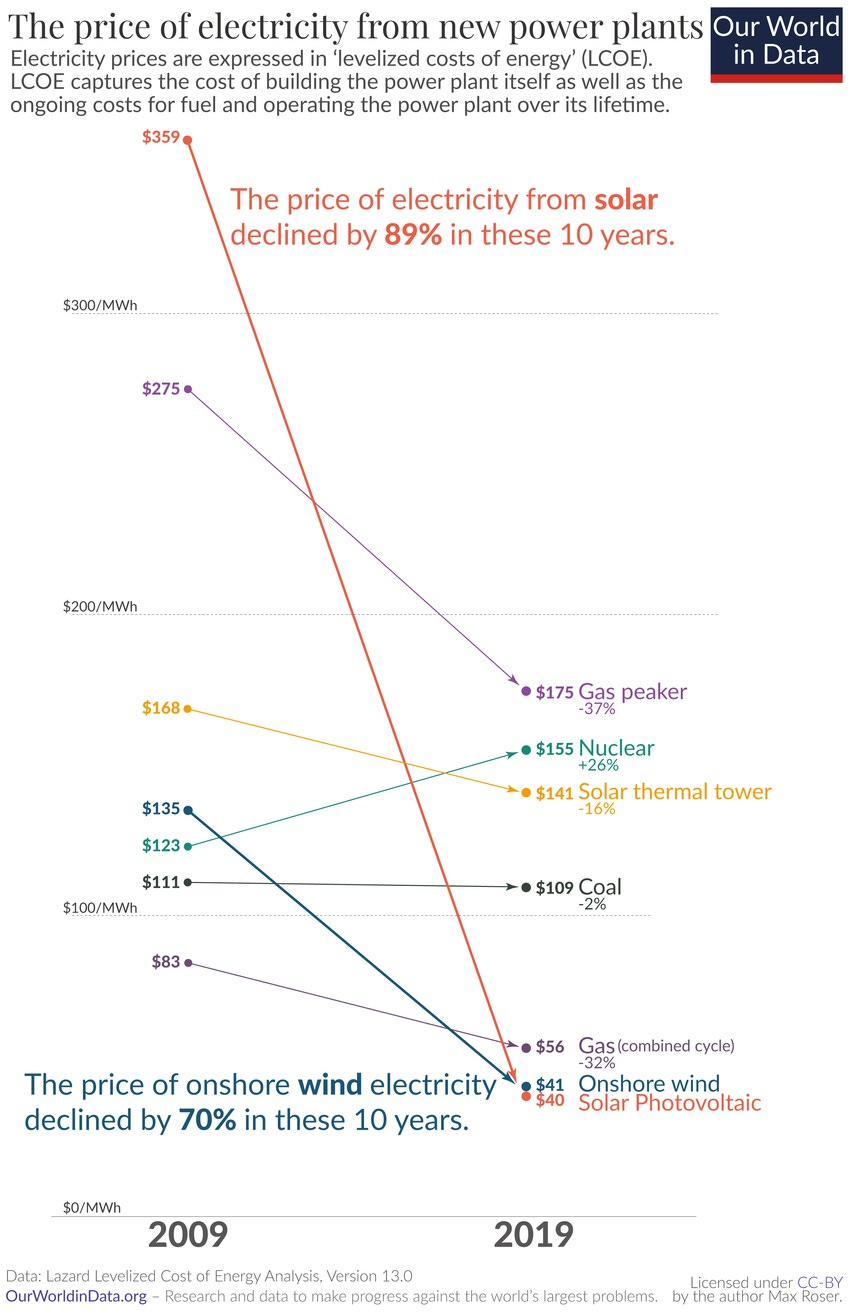

This is a fairly remarkable chart:

And solar has gone down even more since 2019.

I am by no means an expert, but I would really like to see more Thorium reactors, both for their relatively short-lived waste, and of course the fact that its quite hard to build a nuclear bomb using their output.