AIUI - the sender and receiver just have to know the convention for the particular dodec they’re using between themselves. Standardization is not required. And it doesn’t need to have complex instructions written down - you can have an arrangement such “the one I tie a bit of red string to is A”, or “the one on the left of the edge between the largest and smallest holes when the largest hole is on the bottom”, and then go according to some kind of standard Hamiltonian path you both know. That’s not something you need to keep written down, it’s something you can pick up after a couple of lessons (remembering that pre-modern people were much better at memorization than most of us moderns):

An encoding tool is a very interesting idea.

I don’t grasp why Romans would use the Gaulish alphabet for this purpose if they were trying to hide the communications from the Gauls. Why not use Latin or Greek, to make it more difficult for the Gauls to decipher? It was only because Gaulish had the same number of letters as the dodecahedron has vertices?

In vacciprata’s Reddit posts, there is the suggestion that the Gauls were the ones making and using the dodecahedrons, so encoding in Gaulish would make sense. However, that makes it confusing why they turn up at Roman military sites or with Roman coin hordes, but not at Gallic fortifications or with Gallic/Celtic coins.

Are modern scholars misattributing the context of dodecahedron finds as ‘Roman’ when they could just as easily be considered ‘Gallic’? Military sites were captured and lost by either side, and coin hordes had mixtures of coins with many origins. For the dodecahedrons found at burial sites, I wonder if the context was primarily Roman or Gallic.

The system works for many written languages. The technique might have developed in Gaul but used with Roman/Greek alphabet as well.

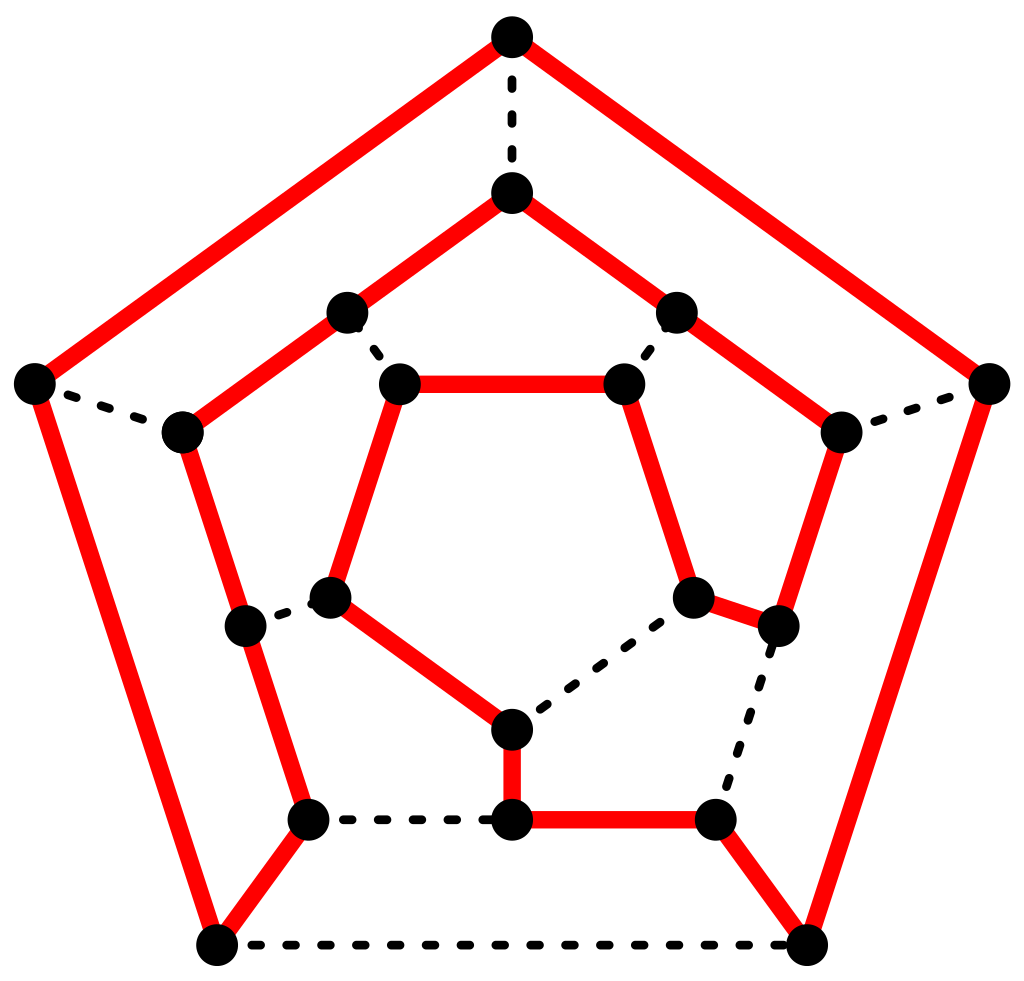

The system described in vacciprata’s Reddit post works for an alphabet with 20 letters. Gaulish used 20 letters. Latin and Greek did not. The Greek astragal (sheep anklebone dice) coding devices had 24 holes corresponding to the 24 Greek letters. Old Latin had 21 letters, I think.

You don’t need the same number of markers as letters. If you have more markers than letters, you either ignore the extras, or include some punctuation marks or something. If you have less, then you just drop a few rarely-used letters.

But you do need standardization. Roman soldiers could be deployed anywhere in the Empire, and the same soldier who’s deployed in one spot right now could be somewhere a thousand miles from there in a few years. If the system is different in every province, then your comms officers either need to learn a new system every time they’re deployed, or know all the systems.

It could be used for Latin only a letter were omitted. The a Latin alphabet at that time had 21 letters. Not a huge problem though.

The thing in his theory that seems most implausible to me is the idea that these things could be thrown over walls. They seem far too fragile for that. But the idea could still work without the throwing part.

The idea that they were designed to be disguised as dice also seems questionable. They don’t look anything like Roman dice, especially when they have a long string wrapped around them, and they’re mostly much too large to plausibly be dice. One wonders why some of them would be so big if this was their purpose; it seems like you’d want them to be as small as possible to make them easier to transport and conceal.

Could they be wrapped in something to cushion them?

The 'secret coder" thing seems to me to be very dubious:

- Roman used roman alphabet, not Gallic and mainly because everyone in a position of power used Latin (or Greek)

- There was already a devise for sending coded messages: Caesar’s chiffre which use a translation in alphabet ( ex: you skip 3 letters and “Manus” become “Pdqxv” in our alphabet.

And a device with a rod of certain diameter around wich you rolled a paper, wrote vertically and then send the paper. To decode you needed the same diameter rod. - the location are consistent with a military use or a use by militaries, but not obligatory related to code.

The Reddit article has a testable proposition: the caption to one of the picture says: “The top and bottom faces have no ornamentation, allowing for an easily-recognizable “upright” position.”

This is far from a perfect test since, as Dibble pointed out, you could mark the starting point with another colored thread. But it would be interesting to investigate whether the various dodecahedrons have concealed commonalities.

Comments:

- That thread might have made the enemy suspicious. But perhaps there was a game developed that involved thread, purely for creating a cover story.

- Perhaps the starting point varied and was intended to be known only to sender and receiver. The dodecahedrons wouldn’t need to be identical, though they would need to be describable, as in, “Start at the Large, small, double ring vertex”. Something like that could be encoded in a separate object.

That is what I think so too, there are examples of modern day dodecahedroms that were used nominally as paperweights, but the use of zodiac signs on the wrapper points to other uses. In any case, while they are likely not related to the ancient dodecahedroms, the way they use the metal knobs to hold the leather wrapper, points to a very similar application of leather or other soft materials wrapped around the ancient Roman Dodecahedrons.

They’re nothing alike. The knobs on the Roman examples are cast protrusions. The studs on the later ones are upholstery pins, driven into the wooden core, after application of the leather.

The strength of the argument is greatly helped by the fact that it pretty much dissolves any objection of the form ‘yeah, but that seems really awkward’ - if there was already a system of encoding messages by threading drilled sheep bones - which seems hellishly awkward, but there it is.

If the dodecahedrons had, as I suspect, removable covers for different occasions, then stud pins would not work. You are correct that they are pins in the modern ones, but the point was that IMHO the metal knobs had a function, so the dodecahedrons are not related as I suspected, the shape was pointed out to explain how the dodecahedrons would had rolled in the ancient times.

In convergent evolution, the overall structure is what counts, not what elements what convergent evolution used to get to the apparent shape.

I’m not even really seeing how convergent evolution has much relevance.

If there was some sort of continuity of tradition between the Roman dodecahedron and the modern leather ball with pins, there might be a reason why pins were added to the wooden model to emulate the appearance of the bronze one, but if that continuity existed, for nearly two millennia, there ought to be a bit more documentation on the whole thing, but there doesn’t seem to be any.

It was just a metaphor. One can point at the likely batteries from ancient Babylon and then find that they were rediscovered but the reasons they were used are different from the modern ones. BTW, I was not saying before that there was continuity with the ancient dodecahedrons and the modern ones. Just that the outside materials shape and similar way they behaved (making them easy to roll, that was the point) leads to solutions that are similar in different ages. And just like the alleged ancient Babylonian battery, there was no continuity with that ancient one and the modern tools.

I understood those to be quite unlikely to have been batteries, but I take your point.

In the time period of these finds, Gauls were Romans. These seem to date to well after the conquest of Gaul.

They are in no way ‘likely’. That’s just pseudoarchaeology bullshit on par with ancient astronaut theories.

Ah. So, if they were a code device, the Gallo-Romans might have been using them to pass secret messages in areas where they were threatened by Germanic tribes or other enemies?

Or messages in internal Gallo-Roman political disputes, or secret financial information, or religious secrets…