(Long post coming up. Sorry.)

That’s absolutely true. I would add that, in addition to moral concerns regarding the rights and welfare of the slaves themselves–and whether or not most white Northerners considered blacks to be their equals, those definitely played a major role in the anti-slavery movement; after all, buying and selling and owning people was pretty fundamentally incompatible with the philosophy of the Declaration of Independence–there was additionally a lot of concern that slavery was inimical to the principles of republican government among white men.

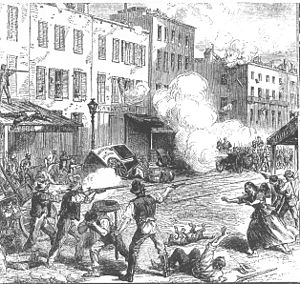

The need to guard against an uprising by the slaves meant that the rights of even white men had to be curtailed–thus, the “Slave Power” insisted that “incendiary” tracts couldn’t be sent through the U.S. Mail on the grounds they might incite “servile insurrection”. Anti-slavery views became, not just something that most people in the South didn’t agree with, but something the open expression of which could not be tolerated, even if it mean telling white men what they could and could not openly say. The “gag rules” concerning the debating of certain anti-slavery resolutions in Congress were a seemingly minor thing, but a lot of people outside the South really resented them–even if someone had no desire to interfere with slavery in the District of Columbia, being told that the United States Congress didn’t even have the right to consider the subject really rankled. (William W. Freehling in his two-volume history Road to Disunion has a thorough discussion of the dynamics of the “gag rule”, and also of the issue of sending anti-slavery literature through the U.S. Mail.)

There was also a lot of suspicion in the North that the habits of mind engendered by owning people–especially large numbers of people, as the big plantation owners did–would inevitably result in a certain aristocratic attitude, and that such quasi-aristocrats would never see their fellow citizens–even other white men–as being truly equal to them. The rise of the Republican Party also saw some quite modern concerns about the concentration of wealth represented by the big plantations as leading to an erosion of republican values.

There was also a good bit of resentment among Northerners–who liked to believe that “honest work” was the way to get ahead in life–of the very old aristocratic attitude you tend to find in any slave society, that hard physical work is something for inferiors to do, not free men. In the Northeast and the Midwest and the West, there was the attitude that a man who was willing to work hard could make something of himself–clear a farm on the frontier, build a factory out of nothing. To the aristocrats of the Slave Power, “honest labor” was something you compelled other and “inferior” people to do, with whips if need be. (Heather Cox Richardson’s To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party is an excellent discussion of the surprisingly progressive and pro-labor views of the early Republican Party.)

The Dred Scott decision was also huge, as it meant that slavery was no longer just something that existed somewhere else, down South; many Northerners now feared that Dred Scott meant the nationalization of slavery, and its inevitable spread even to the “Free States”–another example of the seemingly insatiable rapacity of the “Slave Power”.

Finally, when the “Slave Power” sought to destroy the Union through secession, then opened fire on a United States military installation at Fort Sumter, I think a lot of Northerners who hadn’t necessarily been all that sympathetic to the anti-slavery cause saw that maybe there was something to this notion that slavery was fundamentally incompatible with republican self-government. Slavery caused disunion and rebellion and war; so slavery would by God well have to go.