One of the core problems is that we are increasingly dealing with complex systems, and we are attempting to treat them as if they are merely complicated and can be broken down and understood through a process of reduction, like figuring out how a watch works.

This is not so much about STEM vs social sciences, but about using the wrong tools for the iob. Complex systems can be found in just about every field, STEM or otherwise. The thing is. as we learn more about complexity and its ramifications we should be more humble about our ability to predict future behaviour or understand in detail what’s going on inside them.

For example, economists like to break down complex interactions in the economy into aggregates like ‘labor’ or ‘unemployment rate’. But in reality there are many unemployment rates, and many different kinds of labor. The more you dig, the more you find. But aggregates are easier to work with in models and equations. It’s kind of like trying to understand a complex ecosystem by breaking it down into ‘animals’, ‘plants’ and ‘food’. Good luck.

Another example is the concept of ‘equilibrium’ - the assumption that variables in economies find an equilibrium, and when shocked tend to to return to that equilibrium. Handy, because we can then model the economy with differential equations and other math. But it’s not true. An ‘equilibrium’ is a temporary meta-stability or stable zone in a constantly adapting aystem. But sometimes a shock causes the entire system to reconfigure or collapse, or after a shock the system will find a new equilibrium different than the old one, and do it in completely unpredictable ways.

If the signals are strong enough, it can look very predictable - until suddenly it isn’t. Raise the price of something, and demand goes down according to theory, Keep doing it, and maybe at some point it exceeds the price of a better alternative and the demand suddenly and unpredictably crashes to zero. Or the price drives everyone to a completely different type of product, and the whole supply chain crashes.

This happened when the luxury tax was passed. Standard models showed that the tax would make money. What happened is that the tax was applied to products that have very elastic demand, and it nearly cratered entire industries until the tax was repealed.

I think we just went through such an event. A lot of peoole assumed that after the lockdowns and COVID things would go back to ‘normal’, or re-find our past equilibria. But that’s not what’s happened. After a long enough period of being in a ‘shocked’ state, the economy found new equilibria, and we are now in the process of discovering what’s different.

For example, large numbers of peoole are now refusing to work in offices. Some sectors of the economy have lost value, and others have gained it. It looks like some of the shifts may be permanent - office space is being converted to apartments in many cities, for example. Some people aren’t going to work at all.

Looked at in aggregate, we have very low unemployment. But that hides the severe dislocations that have happened in specific job sectors. Service jobs lack workers, factory jobs lack workers, but the job participation rate is down substantially since pre-Covid. Lots of people sitting at home while jobs need doing, because of a new mismatch between the jobs available and what people who trained for or are willing to do.

Complex systems have the characteristic that they can look simple from a distance, but get increasingly complex as you dive into them. In comparison, a watch can look very complicated (watch movemrnts are literally called ‘complications’), but as you take them apart and look more closely they get simpler. And if you can understand how the parts fit together, you can understand the whole watch.

It’s the opposite for complex aystems. And because complex systems’ behaviour is driven more by interactions between parts than the characteristics of the parts themselves, once you drill down to a certain point the behaviour of the system is no longer visible. Detailed study of a neuron will not tell you much about a mind and what it’s doing.

Even standard methods of testing theories in economics are suspect. For example, predicting future behaviour by looking at the past behaviour of a complex adaptive system is fraught with peril. All you are really seeing by looking at the past is the particular directed random path the economy took before - an economy that no longer exists. Sensitivity to initial conditions means that even if you could go back in time and re-run events, the economy might respond in a completely different way. So not only can you not predict the future, you can’t even say that what happened in the past would happen again if you could do it over.

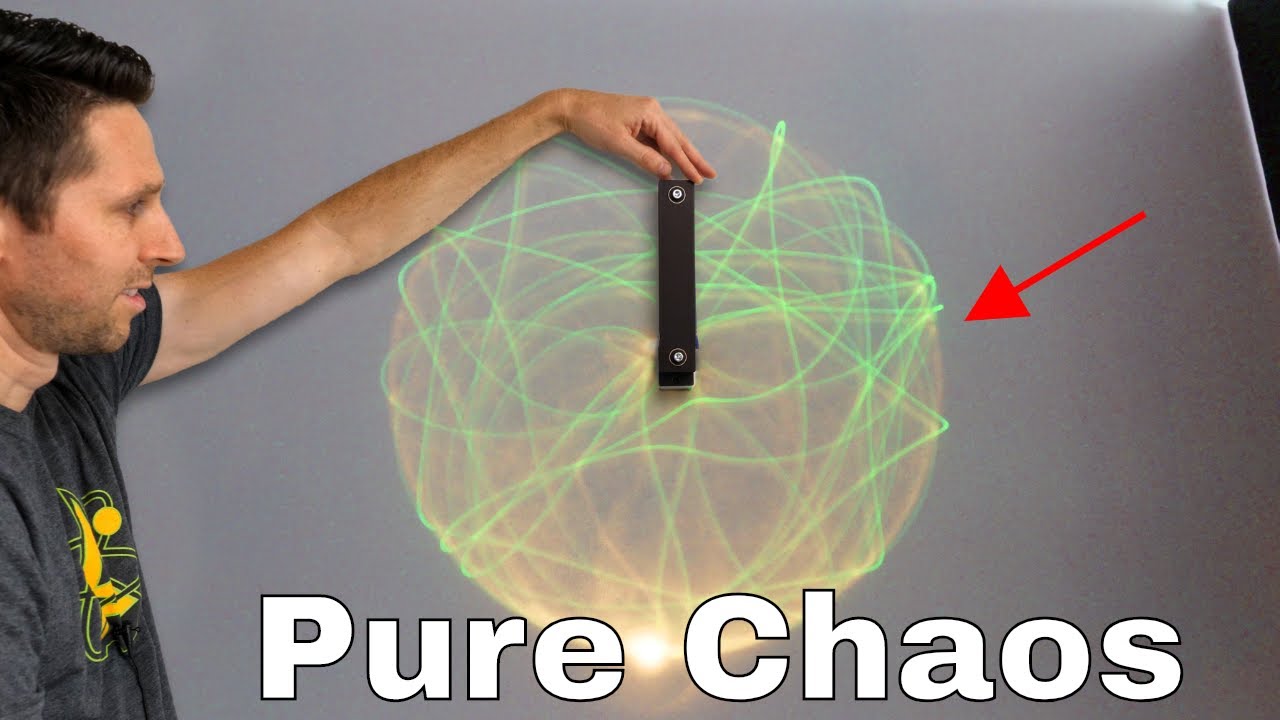

One caveat: Complex systems CAN be predictable in a certain range, if the forces are strong enough. Complexity happens ‘on the edge of chaos’. For example, if you swing a double pendulum hard enough, its behaviour is perfectly predictable at first. But as it slows down, eventually it will go chaotic and completely unpredictable. Then as it slows down further it becomes predictable again as it will just swing back and forth.

Like rhe pendulum, you can predict certain responses in complex systems when the changes are big enough. Raise taxes on boats 50%, and it’s almost certain fewer boats will be made. But from there, and over time as feedbacks happen and the economy adapts, it gets harder and harder to see what will happen. What will the economy look like ten years after the boat tax? No one knows. Anyone who says they do is lying, no matter how much math they use.

One reason why I believe ‘experts’ are losing credibility is because too many of them are claiming expertise over things where expertise isn’t possible - like predicting the GDP effect of a legislative change ten years down the road.

In fairness to many of these fields, they get a bad rap because of a media selection process. Predictions sell, so a reporter calls an economist and asks, “How will the new budget affect GDP over five years?” If the economist says “How should I know? I’m an economist, not a fortune teller,” the reporter will just keep calling economists until they find one willing to step out on a limb. Then the headline gets written as, “Economists say…”

And there is big incentive for being one of those guys. You get fame, the school gets fame, etc. You get to go on talk shows, and you can write books and make money. Try making money on a book titled, “The future? Hell if I kmow.”

And if you make enough predictions some are bound to be correct. So you downplay the misses, play up the hits, and it looks like you are expert in predicting what will happen.

That’s also how psychics do it.