I mean the kind of thing Tolkien would have considered medieval literature. Works in Old or Middle English, and French, Italian, and perhaps even Spanish from the same period.

Perhaps I should have called it ‘Medieval Romance literature’.

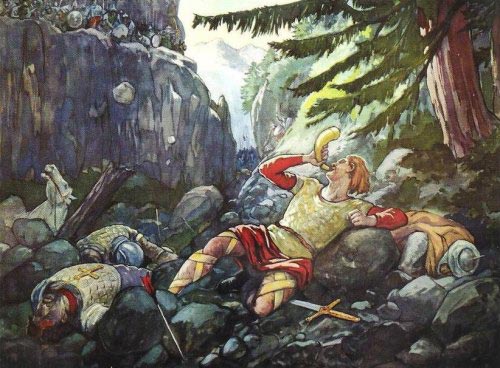

Tolkien was certainly very much into Norse, Finnish, and Celtic epics and mythology, and drew on them extensively, but this aspect of his works (attitude to women) comes distinctly from those Romance language epics and stories about knightly deeds, refined and/or magical ladies, and courtly love.

Tolkien Letters - letter to Michael Tolkien 6-8 March 1941:

There is in our Western culture the romantic chivalric tradition still strong, though as a product of Christendom (yet by no means the same as Christian ethics) the times are inimical to it. It idealizes ‘love’ — and as far as it goes can be very good, since it takes in far more than physical pleasure, and enjoins if not purity, at least fidelity, and so self-denial, ‘service’, courtesy, honour, and courage.

Its weakness is, of course, that it began as an artificial courtly game, a way of enjoying love for its own sake without reference to (and indeed contrary to) matrimony. Its centre was not God, but imaginary Deities, Love and the Lady. It still tends to make the Lady a kind of guiding star or divinity – of the old-fashioned ‘his divinity’ = the woman he loves – the object or reason of noble conduct.

This is, of course, false and at best make-believe. The woman is another fallen human-being with a soul in peril. But combined and harmonized with religion (as long ago it was, producing much of that beautiful devotion to Our Lady that has been God’s way of refining so much our gross manly natures and emotions, and also of warming and colouring our hard, bitter, religion) it can be very noble.

Then it produces what I suppose is still felt, among those who retain even vestigiary Christianity, to be the highest ideal of love between man and woman.

And then, of course, there is Tolkien’s own relationship with his wife, reminiscent not only of Beren and Luthien, but also of Aragorn and Arwen:

Having the romantic upbringing*, I made a boy-and-girl affair serious, and made it the source of effort. Naturally rather a physical coward, I passed from a despised rabbit on a house second-team to school colours in two seasons. All that sort of thing.

However, trouble arose: and I had to choose between disobeying and grieving (or deceiving) a guardian who had been a father to me, more than most real fathers, but without any obligation, and ‘dropping’ the love- affair until I was 21. I don’t regret my decision, though it was very hard on my lover. But that was not my fault. She was perfectly free and under no vow to me, and I should have had no just complaint (except according to the unreal romantic code) if she had got married to someone else.

For very nearly three years I did not see or write to my lover. It was extremely hard, painful and bitter, especially at first. The effects were not wholly good: I fell back into folly and slackness and misspent a good deal of my first year at College. But I don’t think anything else would have justified marriage on the basis of a boy’s affair; and probably nothing else would have hardened the will enough to give such an affair (however genuine a case of true love) permanence.

On the night of my 21st birthday I wrote again to your mother – Jan. 3, 1913. On Jan. 8th I went back to her, and became engaged, and informed an astonished family.

*I think that by “Having the romantic upbringing” he means being brought up on literature idealizing women and noble love, as in Romance literature.