The Berbers are/were a broad ethnic group in North Africa, west of Egypt. They are mostly Muslim since the conquest of North Africa in the 7th century. One significant aspect of the Muslim conquest of Spain was that the generals were all Arab, but the rank and file were mostly Berber which let to some internal ethnic tensions.

Their population is similar to that of the Kurds but I don’t recall ever hearing a claim for an independent Berber state.

They’re afraid they’d be carpet bombed if the pushed for statehood.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berberism

Although, from the sound of it “Berber” does not describe a close-knit identity, but an overarching term for various related groups, like the Tuareg.

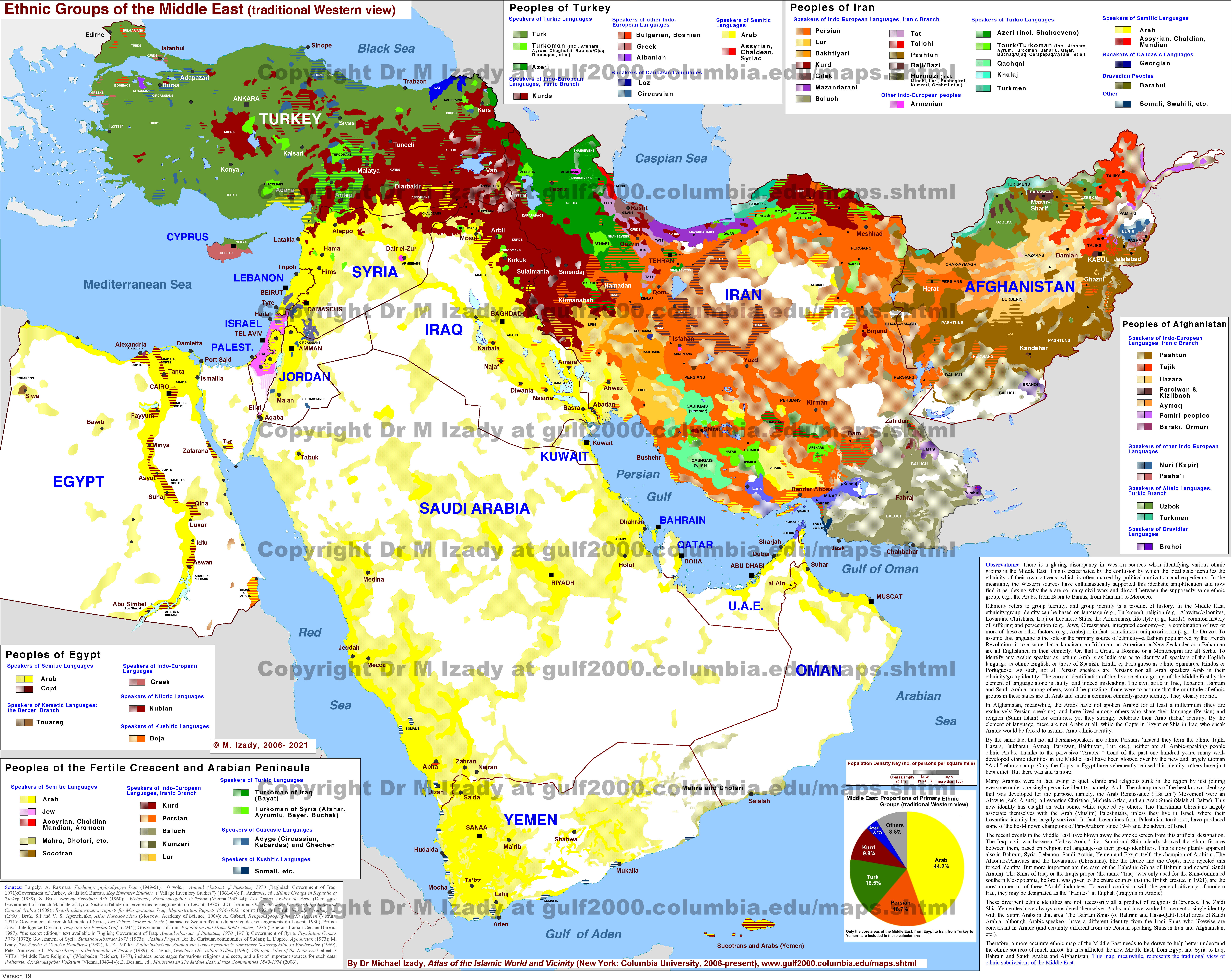

Here is an ethnic map of the Middle East.

It looks awfully complicated, probably as a result of various empires sweeping in and out over the past few thousand years.

Is nationalism a real thing? Yes. It varies a lot but many of the ‘created’ countries have strong patriotism. I’ve met patriotic Pakistani non-Muslims, and separatist Pakistani Muslims.

Kurds are an ethno-linguistic group, though some do have their own religion (Yazidi) and many keep unique traditions along with their Islamic practices. Islamic law traditionally gives legitimacy to a lot of what is called ‘customary law’ so this is not unusual. They inspire ethnic tensions revolving around their separatist tendencies and their minority status. Arab identity is heavily and purposely tied in with Islamic identity and carries a colonialist impulse to this day. This is a source of tension and outright discrimination in North Africa with the Amazigh (or Berbers).

In that vein, IIRC the problem with bin Laden and the Afghans was not that they looked down on the Arabs, but rather that they felt the Arabs looked down on them. Pro- or Anti-Arab sentiment is often a political marker in the non-Arab Islamic world that carries a lot of significance.

Secularism has a very complicated, varied, and violent history in Islamic countries. However, without getting into the specifics, and treating it as an identity marker, people in Islamic countries who are for ‘secularism’ tend to be very self-conscious of this fact and favor specific groups and policies in their respective countries, that may or may not strike an American as ‘secular.’ While Islam does not have a priesthood as such, it does have a scholarly/religious class that is still quite identifiable in many places and often has a political role.

Racial divisions have always been an issue in Islamic contexts, and often relate closely to the massive slave trade that existed before colonialism and persists in unsavory ways today. The issues today, though, are very case-specific. In Sudan, there is conflict due to agrarian vs. herder divisions, economic divisions, desertification, colonial government structures, and many other factors.

Tribalism varies from area to area and person to person. Kazakhs, for example, can tell you what tribe they belong to and so forth, and tribal influence is informally balanced in the government, but it doesn’t matter that much. Systems of trust and loyalty vary from place to place too.

There are many, many major divisions among Sunni and Shia Muslims that deserve their own thread or two. However, I don’t think that the Sunni-Shia ‘split’ is analyzed usefully in the West. There is always the annoying tendency to fit Islamic concepts and phenomena into Christian categories – Sunnis and Shias are like Protestants and Catholics; Islam needs a ‘Reformation;’ Sufism is Islamic mysticism; Salafis are like Biblical literalists; etc. I am not immune from this impulse but it is rarely useful. Unfortunately, the prevalence of Western thought in the world is such that modern Islamic thinking often uses this mentality too, even when they are saying they are against the West.

Major philosophical divides exist and matter but I think these traditions are not really coherent.

On Central Asia:

Most of the indigenous ethnic groups of Central Asia identify as Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school of Islamic law. Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmen, and Kyrgyz have Turkic languages (even if their ethnic origins are not always clear), and Tajiks speak a Persian language. While Russian has disintegrated in some places as spoken language, it is still widely held as a language of inter-ethnic communication, and is the preferred language of many non-Russians in areas of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, as well as by many urban people and migrant-workers. Language politics is a big source of tensions across the region, as local governments try to promote the official language over the many languages that are often spoken in an area. Russians and other European locals sometimes face varying degrees of discrimination, but are usually well integrated where they are. The traditional churches of European ethnic groups, such as the Lutherans, Catholics, Jews, and especially the Russian Orthodox, generally have good relationships with the governments and their ethnic practitioners often have much less trouble than Muslims. Faiths or sects identified as ‘non-traditional’ often have some problems, and the governments clearly function as religious actors despite loudly claiming to be secular. Generally speaking, religious policy in the Central Asian states has maintained remarkable continuity with the Soviet era. Central Asian Islam emerged from the Soviet era as traditional (meaning, not Modern), national, and private. It remains varied but quite unique. Each country’s Islamic structure is increasingly centralized and controlled by the government.

The Soviets moved ethnic groups (who were already mixed up) around a lot, and this remains an issue in much of Central Asia. In Kazakhstan, the government promotes the country as a secular land of multi-ethnic and multi-religious harmony. Ethnic divisions are not very serious, though not without problems. In Uzbekistan, the linguistic Turkification (over Persian) of many areas continues but with some pushback. Tajiks make noise about Samarqand and Bukhara being “theirs” but aren’t in a position to do much about it. Uzbekistan shares the Ferghana Valley with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and it is a scene of conflict, diversity, and reported Islamic extremism. Tajikistan, the odd-man-out linguistically, is home to the Ismaili Shia Pamiri ethnic group and the region’s only nominally Islamist political party, the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan. They are not very popular. A large minority of Uzbeks is perpetually a source of tension. Authorities in the region are very suspicious of overt religiosity and are wary of influence from Muslims abroad, especially the Saudis. They don’t usually like Sufis either.

Missed the edit window: Jews in Central Asia are pretty well integrated AFAIK but I shouldn’t have listed them with ‘traditional churches of European ethnic groups.’ Some were moved there by the Soviets but many have roots there going back centuries. That sentence was poorly constructed.

Central/South Asian politics is fascinating.

Don’t know anything about Afghan views on Bin Laden and him being a Saudi.

I think many of your questions depends varying on different countries in the region.

- One example would be Israel, though more due to land though religion certainly plays a big part. Lebanon is another example, Maronite Christians vs Muslims, as the 1975-90 civil war.

- Iraq is a good example.

Kurds are not the only stateless minority, in North Africa Berbers have been struggling for recognition of their cultural rights.

Iran itself has so many different ethnic groups, Persians are only half. There are Azeris, Turkmens, Kurds, Baluchi, Arab, etc.

Bin Laden came from a rich family in Saudi Arabia, where Wahhabism (or Salafism), a radical fundamentalist form of Sunni Islam is prevalent. The anti-imperialist political mission: first anti-Soviet, then anti-Western, it is accompanied by a radical religious message. This often conflicts with the local form of Islam, which often finds itself outgunned.

The Arab Sunni nationalist governments in major countries like Egypt, Syria and Iraq that united these countries has now broken down because of either war or civil war and this is giving radical factions a chance to seize power. If they lose, they take their weapons to another state that is vulnerable, where central authority has been weakened. This seems to be the pattern that took place in Afghanistan, the Horn of Africa and Libya and now central Africa.

I guess you could compare it to communist revolutionary movements during the cold war, where the spread of liberation movements spreading the ideology was encouraged by the Soviets.

In this case the support is provided by oil money leaking out of the wealthy oil states by renegade rich kids who resent foreign political influence and dream of an independent Islamic state united under one form of the religion.

However, that is just on aspect of the political tensions in the area. The sucessionist ambitions of the Kurds who want to carve out a nation of their own from Iraq, Turkey and Iran is another.

The influence of Iran, where the state religion is Shi’ite Islam is also significant. This also arose as an austere religious movement adopted by the radicals that overthrew the Western influenced government that preceded it. The Iranians support Shi’ite political movements in Lebanon and in Iraq, where the Shi’ites are currently in control of the government.

Iraq is becoming the perfect storm, where all of these conflicts come together. The fear that the uprising in Syria will spread and destabilise the surrounding region has come true. Whether we will again see a terrible war such as that between Iraq and Iran in the 1980s, is doubtful. In that case it was between two centralised states with huge armies reduced to a war of attrition. This situation is far more chaotic and fluid. The divisions within Iraq, where the Sunnis had been marginised in favour of the Shi-ites, have rendered its national army weak and ineffective. It is more like a civil war encouraged by insurgents from Syria. Another Syria would be a humanitarian disaster for the region.

One thing is sure, war costs money and that money is coming from the Sunni controlled Gulf states on one side, diverted from the Syrian conflict, faced against the Shi’ites of Iraq supported by Iran.

The role of the US in all of this looks highly ambiguous.

Stay calm and keep fracking?