There are no newer galaxies far, far away. The galaxies far, far, away are the same age as the galaxies close, close to here.

But there are newer galaxies close to here. Galaxies vary in age, they are not all the same age, so there would be older and newer galaxies far from here. We can only see the older ones though, because the light from the newer ones has not arrived here yet.

But you still get the same mix of old and new galaxies everywhere, and they don’t vary that much in age.

I suppose so. I mean, the concept of the amount of time it would take for all life in the Universe to die off due to all the stars extinguishing is pretty mind-bending, but yes…I guess I do assume that there will always and forever be life (and stars).

I can’t wrap my head around the Universe running out of hydrogen, etc for new stars to form. Hell, a lot of that detritus comes from big, old stars exploding. Isn’t it a self-renewal process, or is there no hydrogen being expelled by supernovae since those stars have burned it all away already?

A star will only burn about 10% of the hydrogen it starts with, before dying somehow or another. But the hydrogen that is burned is gone forever, and there’s no significant source of new hydrogen in the Universe. So yes, it is being continually diminished.

How do stars “capture” the hydrogen to begin with? Is it a product of proto stars heating up?

Almost all of it was created in the big bang.

The matter coalesced into stars after disparate particles created an accretion disk which collapsed into an object that gained enough mass to start the nucleosynthesis process.

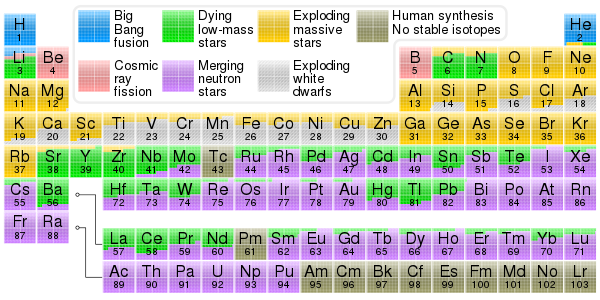

This chart will show you the origin of most of the materials

Stars don’t really capture hydrogen. They are the hydrogen.

I guess I just don’t understand. My impression is that when stars die, the first step is gravitational collapse that allows the star to start burning helium as it’s hydrogen supply wanes. Chronos says that stars only use about 10% of their hydrogen when this happens. I’m confused.

Stars are onions, not teapots. (The core material doesn’t convect or stir with the outer layers, so what happens in Vega’s core stays in Vega’s core.)

But if Vega explodes and 90% of it’s hydrogen is expelled into space, it’s just …gone?

Vega is not massive enough to supernova. However, it will go through a red giant phase. At the end of that phase, its atmosphere will be ejected and form a planetary nebula (which have nothing to do with planets, they just looked a lot like planets to early astronomers). The atmosphere is mostly hydrogen, so this returns some hydrogen to the interstellar medium.

There’s also some hydrogen returned as stellar wind throughout the star’s life. However, these only return a part of the star’s mass. There’s still some hydrogen in the remaining white dwarf as well as the hydrogen that was “burned” to make helium and other heavier elements. So stars reduce the amount of hydrogen available to make new stars. (In the case of Vega, I think around a third of its initial mass (which is 90% hydrogen) ends up in the WD.)

But note that the hydrogen ejected from stars in either manner is too hot to immediately form new stars. The gas clouds that collapse to form stars are very cold, somewhere around 10 K, while the stellar wind and ejected atmosphere are much hotter than that ( > 1000 K). So it has to cool off which takes a very long time.

Swish.

Actually, three-quarters of stars, at least around here, are convective M-class dwarfs. Almost all of the stars that we can see at a glance are onions, but what we can see is a fairly small minority floating in a sea of teapots.

And to help fill in the dots, once all the Hydrogen is consumed heavier elements undergo nucleosynthesis in turn until a large portion of the core is made from Iron.

Fusion of Iron into heavier elements is endothermic, meaning it takes more energy than it releases.

The elements leading up to Iron’s fusion is exothermic, meaning it releases more energy that it consumes.

Once the core reaches Iron nucleosynthesis stops.

Sorry, I didn’t know or look up Vega’s solar mass before making that comment. So hydrogen taking a “very long time (to cool enough to be useful to a protostar’s development)” is how long, exactly? Billions of years? Hundreds of millions? And with space being essentially 0 degrees K, why does it take so long to cool?

I knew that from Astronomy class in college. I forget what it is…is it five solar masses and greater that afford supernovae and everything at or below that goes red giant and that’s it?

Note that the universe is not really that close to absolute zero, and even the microwave background radiation is a 2.725° K. To put this in perspective, scientists on earth now routinely reduce temperatures to below 500 pK or 0.0000000005 K, which is colder than any place in the natural universe.

But it is important to remember that “temperature” is really kinetic energy, and that energy has to be preserved. So it needs to be transferred or emitted as IR radiation and in space.

My very outdated collage text book says that molecular clouds are about 10K and that 0.2km/s. It needs to transfer this energy to something besides warming other members of that cloud.

But this really requires math that the dope doesn’t support the display of to explain.

Space isn’t a bunch of cold matter, it’s a vacuum - and vacuum is a great insulator, as shown by a Thermos. You’re thinking of space being cold, like being on Earth in the winter, but there’s no substance to take heat away, so objects essentially only lose heat by radiation - which is generally very slow.

Ah, okay. But how slow are we talking? And also…if a star is super heating hydrogen by fusion to exude energy on the massive levels stars do, why does the hydrogen cloud/mass/whatever that’s been ejected from a supernova explosion NEED to have the hydrogen to cool before it’s re-used? It’s only going to undergo massive temperatures/fusion in the new star anyway.

It needs to contract, and it won’t contract while it’s still hot. It’ll get hot again after it contracts, but that’s OK, because by then it’s got the pressure from all the hydrogen on top of it holding it in.