I was assigned to base operations. Our division had about 20 military and 30 civilians, our main work area was in the basement of the base headquarters, it was known as the White House. Most of my time was working in communications in the transmitter and receiver sites located out in the middle of the runways. We were also responsible for about 20 remote sites which meant flying and driving to various places. My favorite was the monthly trips to the Boardman, Oregon bombing range. Fly down, spend a few hours making sure everything was working then a couple days visiting a variety of bars and taverns.

We were looking at houses well south of Whidbey air station around Coupeville and wondered why the prices for waterfront homes there were so affordable. Turns out, just over a hill, there is an aircraft carrier deck painted on a short runway where carrier jets practice.

No doubt mentioned prominently by the real estate agent.

“Oh that? Nothing to be concerned about.”

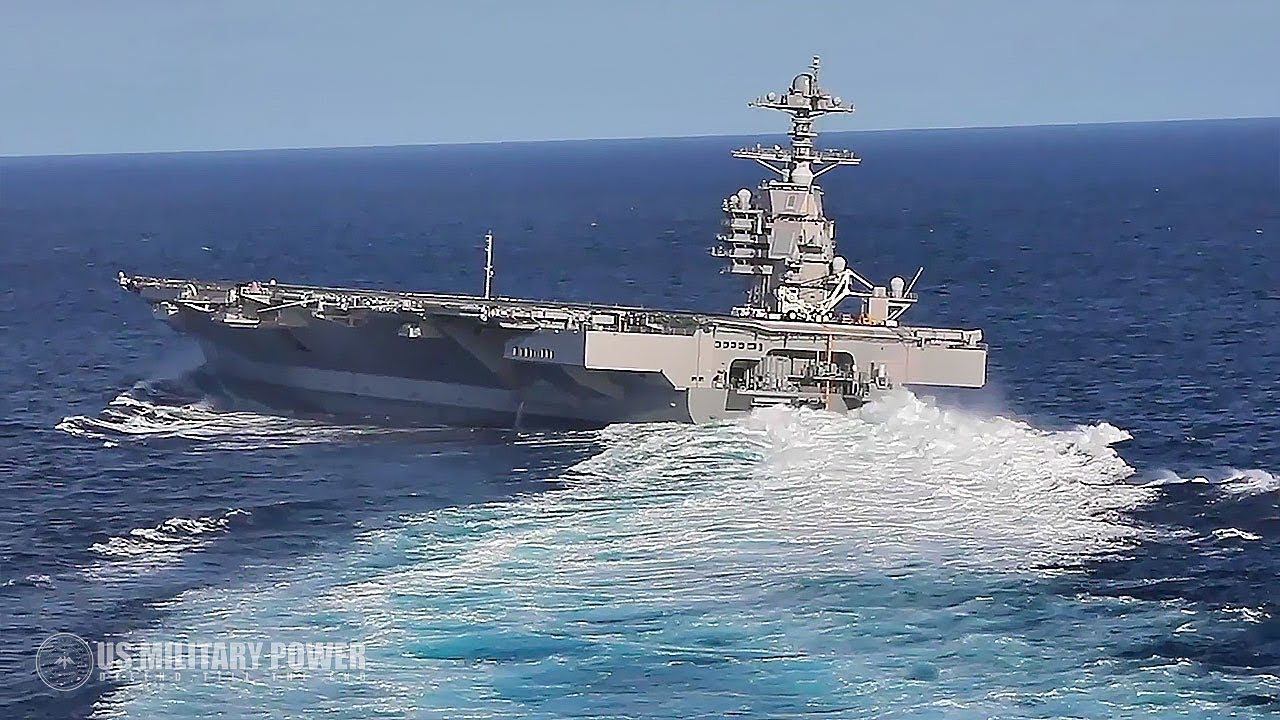

So, how quickly can an aircraft carrier do a u-turn? I’m imagining a carrier steaming across the ocean because it’s deploying somewhere, and it just happens that the direction it’s going in is downwind, and suddenly there’s an attack or something and they need to get birds in the air ASAP. If they mostly can’t launch in zero relative airspeed, then they certainly can’t launch with a tailwind, so they’d have to wait until the ship could turn around.

A carrier travels with a large screening force. Unless something really unusual happened, the carrier would have enough advance warning to do whatever maneuvers would be necessary.

Carriers make 180° turns very slowly. I once had to go down in our “Whale Boat” to help in a man overboard situation. The carrier took at least 20 minutes to turn around and longer yet to return to the general spot where the Airman got blown off the flight deck.

Thankfully by this time one of our escort Frigates had already rescued him. If it was up to just us, he probably wouldn’t have made it. Though I think we did scramble the copters pretty fast. So who knows.

This is correct.

Most importantly is the Mini AWACS (the E2s) we keep up in the air.

These cover a vast area around the fleet and stay aloft for very long periods.

I was a Snipe. I am way out of my knowledge comfort zone as far as details on the planes but the Hawkeyes were pretty damn cool.

[Whidbey Island hijack]

I did a self supported bike tour on the Island – bike to La Crosse, took Amtrak to Everett, biked to Mukilteo and took the ferry I stayed at Fort Ebey, Deception Pass (2 nights) and Fort Ebey (again) State Parks. I was going to do a day trip to Anacortes, but my chain broke so took the bus to Oak Harbor. (I really wished I know about the PBY Catalina Museum, I totally would have visited) The jets didn’t bother me as much as the guy in the campsite near me watching videos with the volume set way up

[/Whidbey Island hijack]

Brian

Not intending to discount your experience, but it looks to my eye like at least some carriers can U-turn in a lot less than twenty minutes:

Granted, that video was taken during sea trials. Maybe they don’t like to have the deck listing so far when they are loaded with aircraft and other equipment (as for a normal deployment)?

A single ship can turn a lot faster than a gigantic formation of ships spread across a few miles. Turning a fleet is a bog job.

But yeah, I was tempted to post the same sort of pic or vid you did.

You’re giving me bad flashbacks when we road through a monsoon and took hard 10 degree lists. Things flew around and lots of unpleasant surprises.

We learned which lockers weren’t secured correctly.

Carriers ride very steady normally. I was never part of a sea trial and was on an old conventional carrier, not the most modern and powerful Nuke Carrier of all time.

We lost a copter off the elevator, during rough seas. The crew had really screwed up securing it to the tie downs.

This is actually was a serious problem in WWII, and had significant impact on a number of carrier battles, one of which was Midway.

The US carriers were chilling out northeast of Midway waiting in ambush at Point Luck for the Japanese carriers to show up. They were in two task forces, TF 16 with Enterprise and Hornet, and TF 17 with Yorktown (and both had supporting ships). Unfortunately for the US, the wind was light and in a southwest direction.

After Kidobutai was discovered by PBY scouting planes from Midway and the Japanese fleet location was transmitted to the USN, the task forces needed to close the distance with the IJN fleet in order to get close enough to launch a strike. TF 17 needed to turn into the wind to recover its scout planes, and this separated the two forces.

Also, when it came time to launch the planes, because wind was light not only did the US carriers need to turn away from the Japanese, but they also needed to reach high speeds to make up for the lack of wind. This meant they had to bring the carriers closer to the enemy first, then turn and steam backwards to launch their planes.

There were other battles where the US also had a disadvantage because of the direction of the wind.

WW2 carriers could either recover or launch planes, but this changed with modern ones that have angled flight decks to allow simultaneous recovery and launch operations from their four catapults.

Conventional carriers could turn quite sharply as well, especially when big chunks of steel and explosives are falling like raindrops. This is Soryu avoiding intended gifts from some visiting B-17s on a nice day in early June, 1942.

Back to the question in the OP, poking around the net, I found an old post on some sort of board that claims the F18 could be launched in port.

There isn’t anything definitive from any official sources, but that’s to be expected. They don’t publish these kind of things.

It looks like the definitive answer is that some aircraft could be launched in some limited configurations, but engaging in a protracted conflict would be difficult or impossible. I had not considered how important headwind is when launching and recovering aircraft.

In the picture above with IJN Soryu, was she able to launch while undertaking such maneuvers? Could a modern ship?

In the movie Sum of All Fears, a US carrier is attacked by Russian aircraft. A “shredder” is shown fending off many incoming missiles, but a few get through. No American aircraft are shown. This always seemed odd to me. In the story, the US has suffered a major event (the nuclear destruction of an occupied football stadium). The President was evacuated to NAOCC and addressing the situation. Wouldn’t all US assets be on high alert by this time? The fighters attacking the carrier would have been spotted a long way off and, given the chaos of the moment, their approach would have been immediately interpreted as hostile and engaged. Where were the alert fighters or those on patrol? Why weren’t other ships in the task force engaging?

For that matter, isn’t it the norm for a carrier at sea to always have a few aircraft in the air at any given time?

Yes, especially the E2s I mentioned earlier.

Good God no. As others have posted, these types of maneuvers are crazy and have people hanging on for dear life. There’s no way that WWII carriers could launch planes while making tight turns.

That’s a plot hole. In the movie, the Russian Tu-22M Backfire bombers (not fighters) attacking Stennis approach by sneaking in under the carrier’s radar, but as has been posted already, the E2 early warning aircraft would pick them hundreds of miles away. The US fighters flying CAP (combat air patrol) would have been sent out to intercept them, but then the movie wouldn’t be Hollywood.

Also note that the same plot hole exists in the original Top Gun where the bogey would have been picked up much further out and identified by an E2. IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) systems had been developed in WWII allowing identification of carriers as yours or the enemy’s and it wouldn’t require visual identification. There wouldn’t have been a possibility of a hidden second bogey. But why let reality get in the way of a good storyline?

That’s a very interesting video, thank you for linking to it. However, we should be careful not to confuse a ship’s speed with the headwind. Yes, the ship was barely moving, but then again it sounded (listening closely to the effect on the camera’s audio) that there was a fair amount of wind that day as well. The wind across the deck is going to be a factor of both ship’s speed and the ambient wind conditions. So while the ship was perhaps making bare steerage way–just going fast enough to be able to maintain a course–presumably it would have been using what speed it did have to keep its bow to the wind. If it was a windy day, it could easily have had 20-30 knots of wind at the right angle to launch aircraft fully loaded.

IANA carrier aviation expert. That’d be my bro, but he’s not here.

Besides the basic question of: “Can you get an airplane on and off the deck with low or no headwind?” there are much larger issues with ships in port.

Fighting the ship takes a lot of the crew on duty. If half of them are off the boat on shore, you might be able to physically catapult a jet into the sky, but who fueled it, armed it, repaired it, spotted it on deck, assembled the munitions below deck, or fed and did the laundry of those who do those jobs? Or supervised all those folks?

I know nothing about nuclear carrier powerplants, but they need to crank up a certain output to generate the steam for the catapults. Yeah, you can whack open the “throttle” on a reactor and go from idle to full output in a second or two. Sometimes the hard part is stopping there without overshoot. But what does a throttle slam like that do to all the rest of the plumbing and machinery subjected to that instant change in heat flux and mechanical stress? I’d bet they still need to be real judicious cranking up the output to avoid breaking stuff.

I totally agree an E2 should / would (?) have known about the bogeys long before Rooster found them with his F-14’s radar. As to the rest of that … Maybe.

Ref KAL 007, Iran Air 655, and a few other minor oopsies, peacetime Rules Of Engagement may well require a visual ID. Original Top Gun was totally a peacetime encounter loosely modeled on

Traditional IFF from WWII to the 1970s amounted to an electronic version of “Halt! Who goes there? What’s the password?” If you get the right answer back you know it’s a good guy. If you get no answer back you know … what exactly? Might be a good guy with yesterday’s codes. Might be a good guy with a broken or switched off IFF system. Might be a good guy whose receiver is just weak enough at this look angle that it’s not picking up your interrogation request. Maybe he’s fine and your gear just failed or is miscoded?

In a peacetime or tensions-short-of war scenario you’ve got a lot of additional considerations. Might be an airliner. Might be a military cargo or reconnaissance aircraft from an unfriendly country but with no ability to harm you. Might be inbound unfriendly fighters or bombers with lots of ability to harm you. But you have no clue whether they intend an attack, or they’re just on a probing mission to tweak your nose & take some pix? The only way to know is to go look and react to how they behave when you meet up. Ideally without causing a fight that wasn’t already part of their plan.

Traditional IFF is still used today. Although the technological and cryptographic features are vastly improved from the early days the conceptual problem remains insurmountable. It’s still just a password and in a peacetime environment (and especially in a highly tense peacetime encounter with teeth bared) there are lots of good reasons to not just slaughter everyone who doesn’t respond with the password before you know who they really are.

Which problem led, in the 1980s, to what’s now called NCTR. That was extremely secret sauce back when I was in the biz 30+ years ago.

I’ll not say more here beyond one small point. No matter how much better it is today than it was in my day, like any tech, it does what it does less perfectly than you’d wish; nothing is an Omniscience Ray. An awesome boon for a warm- or hot-war situation, less so for a purely peacetime encounter.

As to the hidden second bogey, That’s another “Maybe …”

In radar engineering there’s a concept called “resolution cell”. Any given radar’s acuity is only so good. And like your eye, the smallest thing it can distinguish gets larger with distance.

Bog-standard fighter tactics against a well-equipped radar picket defense include running in in groups of 2 or 4 or even more as close as possible to each other. If you’re close enough together, you’re one blip to the radar. Even better, you may look more like a single heavy rather than a batch of fighters / attack aircraft.

As you close on the target, eventually the enemy radar’s resolution cell gets small enough to begin to pick out the individual(s) in your group. At that point you can suddenly multiply their targeting problem by 2x or 4x or worse. If all goes your way, the enemy may become confused enough to not re-sort your threat and re-target all of you successfully before you’re in their shit. Or they may simply not have enough assets close enough to get to all of you before some of you get to whatever they were trying to defend.

Certainly the latest fully computer-controlled missile engagement systems are harder to confuse than some goons with 1970s vacuum tube radars talking via voice radio to some raggedy MiG-21s. But even the latest systems have resolution cell limitations.

Catapult shots do result in a transient spike in steam demand and ultimately reactor power, but that’s all part of what the plant is designed to handle, with appropriate procedures to be followed. Provided the reactor coolant system is operating with a sufficient safety margin to support catapult operations, and the rest of the plant is similarly aligned to support catapult operations, you can launch irrespective of what the main engines are doing. If the plant couldn’t handle such transient demands, it wouldn’t be on an aircraft carrier to begin with.

And it takes way more than a second or two to go from minimum self sustaining power to full power, but that’s got nothing to do with the catapults. The main engines are the real draw.