After I blow-dry my hair (with a typical blow-dryer, like ConAir-1875), if I take a comb afterwards and run it through my hair, I hear “crackles” as I do so wherever the comb goes through the hair. Afterwards, if I simply position the comb somewhere near the head without touching, I see that hair strands rise toward the comb. What’s going on here? That makes me almost unable to comb properly.

Triboelectricity.

You blow dry your hair, removing moisture which would serve to equalize electrical charges in your hair.

Then you run a comb through your hair, generating electrical charge (static electricity) by friction. It doesn’t leak and equalize because your hair is dry. The hair and the comb wind up with different electrical charge, a static electrical potential. The crackling is tiny static discharges where the voltage rises above the breakdown voltage of the interface between comb and hair. It’s like a tiny lightning bolt.

When you separate the comb and the hair, the difference in voltage creates a mechanical attraction force that draws the loose light strands of hair toward the comb, because the charge differential between the two really wants to discharge. (Unlike charges attract.)

What about the blow-dryer itself, does it create some electric charge itself (rather than just the friction between hair/comb later)? I thought blow-dryers did something with electrons. If I were to use an ionic dryer, would that change anything?

The blow-dryer can create a static charge, but it’s pretty weak. The “ionic” dryers are supposed to emit ions which neutralize the charge. I have no idea if they work or not.

If you can to generate a LOT of charge with moving air, suck up a bunch of dry sawdust with a ShopVac. That can knock you on your can…

@gnoitall really knows it all on this topic, but I admit it was the serendipity of @beowulff’s avatar that drew me in…

Purely anecdotally, I feel the static charge is stronger with blow drying as opposed to without.

Some of it would be drying. But, as @beowulff mentioned, the airflow itself generates some static charge.

Triboelectricity is literally rubbing electrons from one surface into another by friction. (That’s what the “tribo-” prefix means.) So any surface contact interaction between two nonconductive materials runs the risk of generating a charge differential.

That’s why “dry” is important here. Water (even vapor) is a pretty good conductor of electricity, and tends to allow charge differences to even themselves out by leakage.

That is why you can get a static electricity shock from carpet in the dryer-air winter but not so easily in the more humid summer.

Another good (man-made) example of triboelectricity is the Van de Graaff generator, which can crank out static electricity charges measured in the hundreds of thousands or millions of volts, simply by continuously rubbing a fabric belt over the parts of the machine.

I have been amusing small children for years by rubbing a balloon on my jumper and “sticking” it onto the wall or even the ceiling.

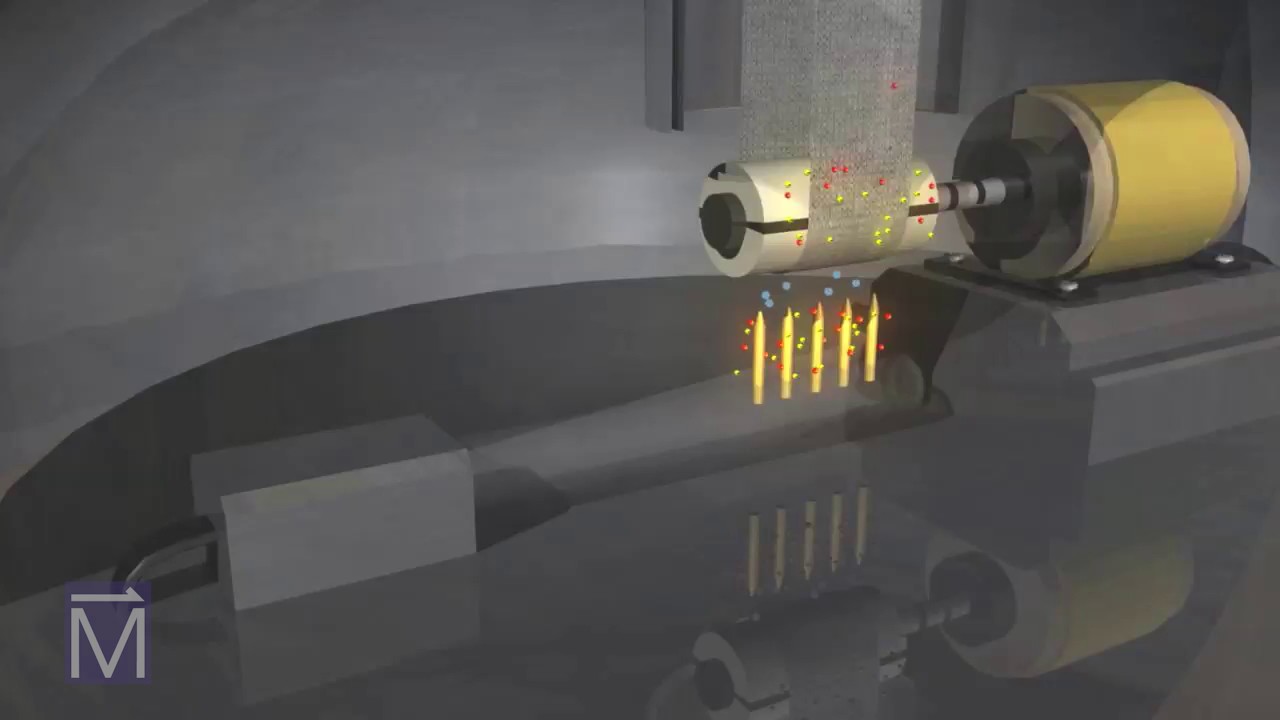

It’s not even frictional rubbing, it’s just contact. More specifically, it is the separation that occurs after contact; that’s when electrons are ripped from their original location on one material and transferred to the other material. Here is plastic sheeting being unwrapped from a roll in factory, creating rather large discharges of static electricity (sparks):

No friction there, just peeling a layer of plastic off of the roll.

And here is a guy who developed a large static charge by crawling around on a truckload of plastic. He generated a spark when he grounded his foot on the truck floor, and lit off a cloud of butane that had collected inside the truck. Don’t worry, the caption says his burns were minor:

In the slo-mo replay at 0:30, you can see the spark when his shoe gets close to the floor.

Before I properly grounded my sandblasting cabinet, I would sometimes experience static discharges so strong that they would make my arm twitch. That wasn’t the shop vac action, it was the actual sandblasting that was creating static charge.

Have you been vaccinated?

On that note, munitions factories are anal-retentive about humidity levels, grounding, and static control.

Same goes for any lab that handles electronics. This is because many MOSFETs can be destroyed with very little ESD energy. In my lab at work, all of our workbenches have to be ESD-certified once a year, and we have to wear an ESD wrist strap when working on things. The strap has to be tested before use. We have to place circuit boards in static-dissipative bags or tote boxes when moving them from one bench to another. Some labs (not mine) also require the floor to be static-dissipative, and ESD shoes or ESD shoe coverings must be worn.

Aren’t there some sort of material properties involved as well? I mean, I got quite the light show this morning when I took my polyester blend socks out of my cold weather socks (wool blend), but as far as I know, if it had been a 100% cotton sock, it wouldn’t have sparked at all.

Yes, but it’s not clear what those properties are. From @gnoitall’s link:

The triboelectric effect is very unpredictable, and only broad generalizations can be made. Amber, for example, can acquire an electric charge by contact and separation (or friction) with a material like wool.

More deeply physics-y people may know current theories about the materials and their triboelectric attributes.

One good general rule is that good insulators are also good triboelectricity generators. Hence, plastics or hair products like wool. Not sure why plant fibers are less so.

Air is another good one. The electric charge buildups that cause lightning appear to be triboelectricity caused by adjacent masses of air spanning tens of thousands of feet vertically and hundreds of miles horizontally.