Or you have some means of testing in situ without cutting a biopsy out of the patient, like any of the current medical imaging techniques. Or you test for some chemical secreted from the cancerous cells, similar to how we use PSA to screen for prostate cancer.

Maybe the solution isn’t a cure, it’s to put the rapidly dividing, immortal cells to good use?

I actually thought of PSA as an exception when I wrote that but I don’t think that most other cancers secrete proteins to the extent that Prostate cancer does, the other case where there could clearly be a test is leukemia in which case a blood test would certainly work. As far as the imaging techniques go, they can indicate the presence of a tumor but not wither or not it is malignant, and in anycase not something that you could do yourself at home from a kit, like we do home drug tests. What you will (and actually are able to do) is to get semi complete gene sequencing to see if you are at high risk for certain cancer types, and as time goes on this information will be come more accurate and more complete.

Disclaimer: I’m not a biologist, and from my work am probably biased in the direction of genetic tests that require tissue (much like benbo1’s sister is probably biased in favor of stem cells), so someone may come around and set me straight.

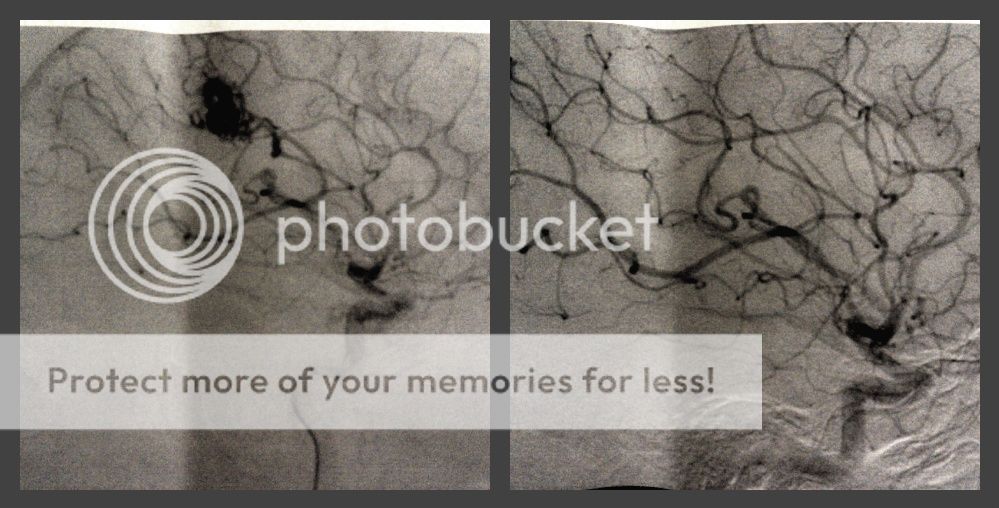

Sorry to bump an old thread. This may be my only post…but thought it was worth it…to post pictures of my daughters before and after gamma knif brain surgey. MRI’s are 6 months apart. Good stuff.

You kind of answered your own question IMO. We have not cured “Cancer” in much the same way we have not cured “Colds”. There are so many variants, causes and treatments that science is in fact curing 100s of diseases.

This is diametrically opposed to say AIDS/HIV which is - generally speaking - a single disease that can be targeted.

I for one believe AIDS will be cured before cancer and would add that AIDS has diverted billions of dollars in research money that might have gone to cancer research.

Not really an answer I know, but my thoughts on the subject anyway.

There are techniques in development that could be generally applicable to a variety of cancers.

Basic research has led to the understanding that many cancers express cell surface proteins that are not generally expressed in healthy cells.

Researchers have figured out how to make antibodies to those cancer specific cell surface proteins.

Now the clever part… researchers have figured out how to attach a powerful chemotherapy drug to that antibody. This combined antibody drug conjugate (aka immunoconjugate) allows targeted use of more powerful chemo drugs than could otherwise be tolerated.

Seattle Genetics has already brought a drug to market using this process. Adcetris targets CD30+ lymphomas and Large Cell Carcinomas.

Conceptually this approach should work with other cancers. 1) Researchers identify unique cancer cell surface proteins. 2) Researchers design an antibody to the cancer cell surface protein. 3) The antibody is incorporated in an antibody drug conjugate.

This approach requires a rethinking of cancer. It is not about breast cancer, colon cancer, or lung cancer. Instead it is about which unique cancer cell surface proteins are expressed in a given tumor (almost*) regardless of where in the body it is. So think in terms of whether a patient’s cancer is positive for CD30, CD15, CD40 or whatever other cell surface protein and then choose treatment accordingly.

It is still early in the use of this process, but there is hope.

*downside is that antibody drug conjugates are large molecules and may not easily pass the blood-brain barrier.

Several years ago I read of a treatment where geneticaly engineeered antibodies could be armed with radiactive isotobes and sent directly to cancer cells. Delivering a much higher dose of radiation directly on target with highly reduced levels overall, this sounded very promising as a treatment that could be custom fit to each patient and cancer potentialy, any more word on this?

Sorry Iggy, I posted before I read your post.

This is an important and promising method of treatment, but it’s unlikely to become a “cure”. Any tumor is going to have a heterogeneous population of cells. Some will have the protein targeted by the antibody, some won’t. The ones that don’t may survive and reexpand into a new tumor. I was just reading a paper about this a few months ago. Really, the more we look, the more complicated cancer is. Within a single patient, different tumors may be made up of vastly different cells, and within a single tumor, there may be many types of cells. The paper I read specifically identified a very small population of cells within a tumor that seem to function as protectors - sort of “master cells” that keep the whole shebang moving along. I forget the details. But it just reiterates the point that’s been made several times already: It’s really unlikely that we’ll ever find a specific treatment that cures all cancers, or even one that will completely wipe out all cases of one kind of cancer.

The problem is that every cancer is unique, because it’s a series of mutations that thwart the body’s very robust anti-cancer mechanisms. Every cancer is arguably “more unique” (if you’ll forgive the expression) than the person who has it, who might be a twin.

For a great book on the subject (though, from 2001, so not quite up-to-date), see Evolution - An Evolutionary Legacy by Mel Greaves.

We won’t be able to prevent cancer, but we will find more and more effective ways to treat many types of cancer, as well as predicting it better and detecting it earlier, and stopping it before it metastasizes. IMHO our best bets will be finding out ways to stimulate our own immune systems to fight it – but that will require significant per-patient engineering.