Richard Pryor.

Christian Vander. Gifted drummer and composer and leader of the French band Magma. They were the creators of zeuhl (“celestial”), a subgenre of progressive rock. Not only that, but Vander devised a language of his own, Kobaian, for the vocals. Not that a new language has anything to do with musical accomplishment, but still.

Without the influence of Louis Armstrong, jazz would probably be remembered as a type of novelty dance music from the 1920s. He transformed it to a soloist’s art form. Today, most people who remember him think of him as that old guy who went on the Ed Sullivan Show and sang things like Hello, Dolly and What a Wonderful World. But when he was young, he was a lion. Other musicians would buy his records just to learn what innovations he had come up with.

Speaking of Bela Fleck, he’s done some crossover work with the incredible Toumani Diabaté who must be the best kora player ever.

I’m lucky to have seen him perform twice.

Also from West Africa, an incredible musician and singer, Salif Keïta - well worth a listen if you do not already know either.

I’d also like to mention Bob Marley, who, while not a spectacular musician (he was good, but not Jimi Hendrix good) gave the world access to reggae through his musicality and stage presence, and with humility.

(I may be biased in this, as he wrote a song about my country, Zimbabwe)

Perhaps a left-field thought but what about James Randi?

As stage magician and escapologist he was brilliant but his talents in applying sceptical thinking, challenging and exposing the charlatans of this world he had no equal.

He was a massive influence on me growing up and definitely showed me and many others the risks of self-deception and what it means to be intellectually honest.

The depth of his skill and importance can be judged by the sort of people who looked up to him and who sought his advice.

He was the one-word answer to the question “who is the best person to test this claim”? If there was bullshit, you needed Randi.

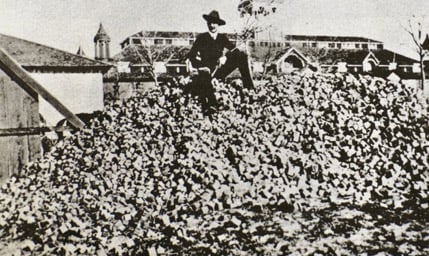

Adolph Toepperwein was probably the greatest exhibition shooter ever. In 1907 he shot at 72,500 wood blocks that were thrown into the air. Each block was 2.25" X 2.25" X 2.25". The blocks were thrown to a height of between 30 and 35 feet, and 25 feet from where he stood.

He missed nine.

It’s doubtful this feat will ever be surpassed.

I’ve seen all three of them in concert, just not together. I hesitated to call them jazz artists. Di Meola is probably the closest thing to a jazz musician, but he and McLaughlin are difficult to put into a niche. Paco is more flamenco, or possibly “new flamenco” like Ottmar Liebert.

Diabate and Keita are two favorites from Mali, along with Habib Koite and of course the late great Ali Farka Toure, who I saw live in concert in Bamako. I’ve seen the others on tour in the states.

Back on topic, I’d nominate a musical group, The Dave Brubeck Quartet. Brubeck made jazz accessible to an entire generation (including me) that had largely ignored it up until he started touring at universities across the country. His unique time signatures made some of his music cross over into pop, and the smooth stylings of his group, especially Paul Desmond on sax, appealed to a large audience.

I’m sure I’ve mentioned it before on the boards, but Howard was a regular at the cafe I worked at in college back in the mid-late-90s. I had no idea who he was when I met him; I just saw he would come in with his harmonica all the time and compose at the table. One night, when we were closing, I asked him a harmonica question, and he pulled out one of his custom Joe Filisko harps and just tore through some bebop lines. I was absolutely gobsmacked–had no idea you could do that with a 10-hole diatonic. Then later I got some context of who he was. Quite a nice guy and we maintained a correspondence for a bit after I moved to Europe.

I have neighbors who named their pug Sweetness.

That is fantastic rifle shooting! It wasn’t a shotgun was it?

Another pick for boxing: Mike Tyson.

Tyson was built different, and freakishly strong. At 13 years old, he was 200 pounds, and was knocking out grown men.

And in his early 20’s he was doing the same to his wife. A top-grade talent certainly but a top-grade arsehole as well.

Bob Hoover. He was known as the pilot’s pilot. It would be difficult to make a movie of his life because it would have to be a long mini-series and people would doubt it actually happened. His life was like a James Bond movie where you go " OH Paaaleeease, there’s no way he did all that"

Fantastic shooting!

I thought of mentioning Hoover, but this was a thread on a ‘talent of a lifetime’, and there was at least one other pilot in his league - his good friend Chuck Yeager. Hoover himself said that Yeager was the best aviator he’d ever known.

Still, I saw Hoover a couple of times at the Reno air races. He used to fly the pace plane at the races and acted as safety pilot, circling above the races ready to help pilots with stricken planes land. When you blow an engine in a Reno Racer, the result is usually a windscreen covered in oil. When it happened, Hoover would manage to form up on the stricken plane almost immediately, and talk the now-blind pilot down to the runway. I think he saved more than one pilot that way.

I saw his ‘energy management’ airshow routine a couple of times. Flying a twin Aerocommander Shrike he’d kill the engines, feather the props, then do a full loop, land, and roll right up to stage center stopping just feet away from the stands, props still feathered. And I saw him do it in a video once with a glass of water sitting on the glareshield. He didn’t spill a drop.

If you throw Yeager into the mix, I could agree that they were the best pilots in my lifetime.

Yes, they’re the canon of Holmesiana. They’re not particularly canonical in terms of defining the mystery genre as a whole. Christie did that.

Yeager and Hoover had similar careers and were both great but Hoover’s life was (IMO) more interesting. rescuing a pilot in WWII and flying him back in a single seat plane. Escaping a POW camp and stealing a FW-190. Bringing a test F-86 back after losing the flight control system… No pun intended but his early flight training was done on the fly and was self taught. Not to take anything away from Yeager but pilots generally refer to Hoover as the Pilot’s Pilot.

Well, there’s no official body that decides genres. The mystery has a very long history and no neat dividing line like science fiction has with the founding of Amazing Stories in 1926. But let’s look at that history.

One clue that immediately presents itself is that the very first genre pulp magazine was Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, which debuted in 1915. However, that was a revived version of Nick Carter’s Weekly from 1903, which followed the Nick Carter Library, which started in 1891 because of the popularity of the Carter character, who debuted in the September 18, 1886 issue of New York Weekly with the first part of a series titled “The Old Detective’s Pupil; or, The Mysterious Crime of Madison Square.” That was a year before Holmes’ debut.

Thousands of detective stories appeared in dime novels, story weeklies, and other magazines in America and just as many in the penny dreadfuls and magazines in the UK in the 19th century. Nor were these confined to minor hacks. Dickens’ serialization of The Mystery of Edwin Drood was rabidly followed up until his death, and Wilkie Collins produced The Woman in White and The Moonstone even earlier. Anna Katherine Green’s The Leavenworth Case (1878) was the first major mystery written by a woman and “one of the all-time bestsellers in the literature.” (Quote from Haycraft: see below.)

The genre got a huge kick with the series of short Sherlock Holmes’ stories starting in 1891, and imitators and rivals and crooks and every type of character flooded markets through the start of World War 1, a “veritable epidemic of detective stories” claimed Howard Haycraft. That was in his 1941 history, Murder for Pleasure: The Lives and Times of the Detective Story. Doyle gets a whole chapter to himself. The pre-WWI period was marked by R. Austin Freeman’s Dr. John Thorndike, Baroness Orczy’s Old Man in the Corner, G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown, E. C. Bentley’s 1913 Trent Last Case, considered by most to be the first modern, Golden Age, mystery, the many mysteries of Mary Roberts Rinehart who was the only mystery writer to make the top ten bestsellers of year in America in the 1920s until S. S. van Dine did in 1928 and 1929, Carolyn Wells’ Fleming Stone, Arthur B. Reeve’s Craig Kennedy, and Maurice LeBlanc’s Arsène Lupin. All of these were known to every mystery lover in 1920. Most of them were still writing in the 1920s and outsold Christie during the 1920s. That’s not including spy novelists like John Buchan, who was one of the bestselling authors in Britain in the 1920s. Dorothy Sayers, an actual scholar of the mystery, started a three-volume historical series with learned introductions called Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery, and Horror in 1928, when Christie had published all of eight books.

Haycraft doesn’t get around to discussing Agatha Christie until page 129, who is merely “first among these, in a chronological sense at least,” of the female post-WWI authors. He has an interesting quote from her.

“Toward the end of the war, I planned a detective story. I had read many detective stories, as I found they were excellent to take one’s mind off one’s worries.”

I’m not sure what additional evidence would be necessary to show that the mystery or the detective story was an identifiable genre with a canon of authors and stories for decades before Christie. If you have cites you’d like to use in defense of your claim I’d like to read them.