I figured the orbital velocity for Mars at 7,800 mph (3.495 km/s); Earth is 17,500 mph (7.85 km/s). Just less than half.

Doubling the delta V requirement roughly squares the mass ratio. So for example, let’s say that you’re capable of building a rocket that weighs 1 ton and accelerates 100 kg to 4 km/s. To reach 8 km/s, you have to stack that on a rocket that can accelerate 1 ton to 4 km/s, which for the same ratio would weigh 10 tons. That’s a total mass ratio of 100:1 compared to 10:1. So it’s 10x as heavy instead of just double as you might expect (or 4x if you’re thinking about raw kinetic energy).

Of course there’s an xkcd for that

Extending on this a bit:

The distinction isn’t always clearly made, but we can separate the ideas of reaction mass and energy input. All rockets work by using energy to accelerate reaction mass in one direction. Chemical rockets get double duty from their propellant: it’s burned, which releases energy, and said energy heats the chemical byproducts, which shoot out the nozzle.

This has some nice advantages, in that there’s no limit to how fast you can burn chemicals, and the energy goes right to heat without any extra conversion steps, and the double duty aspect. But that’s not the only way to build an engine. Ion engines use unreactive chemicals (like noble gases) as the reaction mass. The energy has to come from somewhere else, like solar panels (which accelerate the gas electrically). Solar panels don’t provide much power, so the thrust is very low. But ion engines can be very efficient because they can accelerate the mass to much higher velocities than burning chemicals can (which are limited to a few thousand m/s).

There are intermediate approaches, like nuclear thermal rockets. They can get much hotter than plain chemical rockets, but a nuclear reactor puts out much higher power than solar panels, so they get decent thrust too. NTRs still aren’t powerful enough to launch from the ground, but they don’t take weeks or months to operate the way ion engines do.

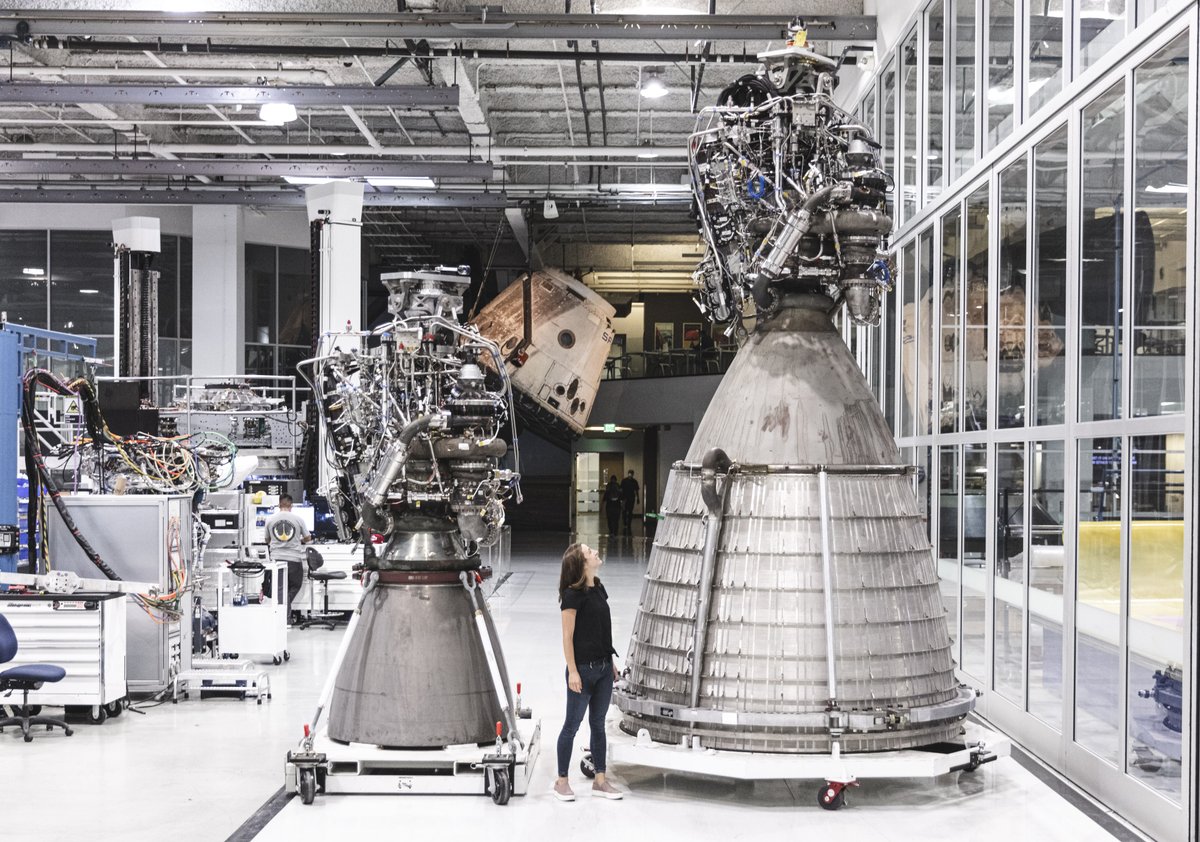

This picture just popped up in my feed and bears some relevance to this thread:

These engines are virtually identical except that the one on the left is made to run at sea level and the one on the right in a vacuum. As you can see, the main difference is that the vacuum nozzle is huge. That’s because rocket engines are fundamentally heat engines, and the expansion of gas is a critical part (just like a gasoline engine makes power when the hot gas pushes the cylinder down, expanding the volume).

A sea level engine can only expand to one atmosphere though and doesn’t benefit from more (in fact it can be damaged). A vacuum engine can expand indefinitely–the bigger the nozzle, the better. Of course there are practical considerations (can the engine physically fit in the spacecraft), but as you can see they can still get pretty big.

Incidentally, just the fuel pumps on these engines make around 100,000 horsepower.

This thread has had some interesting discussion but I don’t think it has really provided an intuition or addressed the comparison in the o.p. between the Saturn V rocket and the Lunar Module Ascent Stage.

The primary concept to understand when it come to orbital mechanics is that everything that is in a gravity well (and isn’t on the ground or otherwise suspended by some restraint or external force) is falling. The difference between an object that is in orbit or the Earth (or Moon, or any other massive body) and one that is not is that the orbiting object is going so fast that it is actually continuously falling above the horizon. If you plotted the trajectory of both and orbital and suborbital object, you would see that they are both ellipses, but the ellipse of the orbiting object is large enough (and properly oriented) such that it never intersects the surface, while the path of the suborbital object does go right into the ground. So, it is not altitude but speed that dictates whether an object is in orbit, and what a space launch vehicle does is apply that orbital component of velocity while raising the payload to the desired altitude.

It was noted upthread that the Earth, unlike the Moon, has an atmosphere which contributes to drag losses. (Technically, the Moon does have an atmosphere as well but it is electrostatically charged dust that is so thin it has no aerodynamic effect.) It is true that some amount of momentum of the space launch vehicle is lost to atmospheric drag, but it is typically only a couple of percent and is not a large driver in the size of the rocket or amount of propellants required. In fact, you can fly very large and aerodynamically inefficient launch vehicles with relatively little penalty, as the American Space Transportation System (“Space Shuttle”) demonstrated. This is because rockets are launched upwards first, to get above the thickest part of the atmosphere before they are going really fast, and then pitch over in what is called a gravity turn to go into an orbital trajectory. (Note that the issue of atmospheric drag is a significant problem for horizontally launched spaceplane concepts because they have to remain in the atmosphere to use the air as a source of oxidizer and a working fluid as well as for lift while getting up to hypersonic speeds; these issues make spaceplanes essentially unworkable.) Having to fly straight up without getting any orbital speed is itself a loss (referred to as “gravity drag”) and essentially all of that momentum is lost in the flight as that radial component goes to zero if the payload is inserted into a circular orbit (or even an elliptical). On an airless body like the Moon a launch vehicle can pitch over almost immediately and minimize the energy spent in just an ascent mode, so there is some saving there.

However, the real reasons that the Lunar Module Ascent Stage are so much smaller than the Saturn V rocket are twofold. One, as noted above, the much lower gravitational potential of the Moon’s field (~5% of that of Earth at the surface) translates as a squared value in reduction in energy required. So, a Saturn V type vehicle designed to fly from the Moon’s surface on a similar trajectory would be ~1/20 the size and propellant capacity, and in fact would actually be less because the rocket wouldn’t need as much impulse to carry all of the fuel it is using throughout ascent, and could have much lighter structure even relative to size by dint of not needing three stages, such powerful engines and support structure, and so forth. The other is that the Saturn V carried the entire Command Service Module, the Lunar Module, and the S-IVB was sized to not only go to orbit but provide sufficient impulse for the trans-Lunar injection (TLI) maneuver. In contrast, the Lunar Module Ascent Stage only needed to carry two astronauts, their pretty minimalist life support and communications systems, and ~50 lbm of rock samples. Not having an atmosphere helped, too, especially insofar as the LM didn’t need any kind of reentry shielding or any kind of aerodynamic fairing, but it really carried far less weight to back to orbit in a much lower gravitational potential field compared to Earth.

A launch from the surface of Mars, which has 20% of the gravitational potential of Earth at the surface would take a much larger vehicle than the Lunar Module (even assuming the same crew complement and payload) but it isn’t enormous. As a first estimate, it would have to have about a factor of four increase in impulse over the Lunar Module Ascent Stage for the same payload. Note that while Mars does have an atmosphere–and a particularly irritating one, being just dense enough to sustain weeks long dust storms and cause aerodynamic heating on descent, but not enough to provide effective lift at subsonic speeds for anything that isn’t a giant glider–in terms of its effective upon ascent it is essentially negligible. It is about 1% of the atmospheric density of Earth’s atmosphere at sea level, so that couple of percentage loss to atmospheric drag we see in space launch vehicles from Earth becomes a rounding error from Mars.

The bigger problem is getting the fuel (and everything else) down to the surface of Mars in the first place. Parachutes won’t work for payloads that exceed 1000 kg, ballutes like the Low Density Supersonic Decelerator are complex to deploy and offer no redundancy should they fail in mid-descent, and fully propulsive landing substantially increases the overall mission mass requirements, which is a direct increase to costs since you also need all of the extra impulse all the way from Earth’s surface to Mars injection just to get that large mass of propellants where you need them. It is for this reason that in situ propellant production is of such interest, as it would eliminate the need to take the propellant needed for ascent along for the ride. However ISPP (and in situ resource utilization in general) are still nascent technologies that have not even been demonstrated to a proof of concept level in an actual extraterrestrial environment, and the complexity of performing complex chemical refining necessary to produce high purity propellants is a substantial technical challenge.

The details of what a Mars Ascent Vehicle would look like and just how much propellants it would need per unit mass of payload depend upon the details of what such as system would be designed to do (e.g. does it need to survive unprotected on Mars for years at a time? Would it use storable liquid hydrocarbons, methane and LOx produced in situ, or some other propellants), but as a starting guess you can imagine something that is about four or five times larger than the LM Ascent Stage and then scale it for the greater number of crew (usually assumed to be six people) and additional samples to take back. This is certainly well within the range of a single stage to orbit (SSTO) vehicle given that only has to provide ~20% of the impulse of a comparable SSTO launched from Earth. However, you have to have high confidence that it will work, because unlike launching from Earth, if you have to abort upon ascent you cannot use parachutes to bring the crew to a safe landing.

Stranger

Welcome back, @Stranger_On_A_Train!

It will be very interesting to see how SpaceX solves the propellant problem. Their propellant of choice–methane and oxygen–can be produced on Mars using ISRU. But they face some serious obstacles, the top three of which are (IMO):

- Extraction of water from the surface. While there is plenty of water on Mars, it is not all easily accessible, particularly far from the poles.

- Power requirements. They need hundreds of kilowatts to generate enough propellant over the course of a couple of years. Basically, there’s nuclear and solar. And nuclear probably just isn’t going to happen–too much development. Solar can work, but will require thin-film technology with a robust deployment mechanism, like something that just unrolls. They’ll need many acres of solar panels.

- General operation of the ISRU machinery. It will obviously need to be incredibly reliable and resistant to environmental factors like dust, since it will have to operate autonomously for years.

There’s more, obviously, and those three things themselves have numerous subproblems, but those are the main high-level problems, IMO.

Would it make sense to have a separate rocket and ascent system for the samples? One that could make use of ISPP produced fuels, and therefore have a less strict safety margin? Would suck to lose the samples, but would suck far, far more to lose the crew.

You also have absolutely no infrastructure or resources to do any sort of recovery and rescue mission. Even if you had a system that could abort and land safely, they’d still be screwed.

Given that returning samples is a key objective of the mission, I would argue that it is just as crucial as safe return fo the crew since that is why they have risked their lives to achieve. But really, either you have the capability to produce propellants in situ or you don’t, and the complexity of having to deliver two ascent vehicles and coordinate an ascent is not worth any theoretical advantage to reliability.

In addition to the three challenges identified by @Dr.Strangelove, another issue is just the infrastructure and logistics of handling large amounts of bulk propellants and delivering them from where they were extracted to and into the ascent vehicle. At terrestrial launch sites, propellants are generally delivered to the launch facility by truck, stored in controlled tankage at a safe distance from the gantry, and delivered to the launch vehicle via pipelines, pumps, and flexible hoses. While the actual fueling operations are done remotely, manipulating and maintaining all of this infrastructure is done by human labor. While this could in theory be automated, delivering and assembling this entire structure autonomously while coping with the contamination of the Mars surface environment is problematic at best. This really argues for spending the effort and budget on building up a solar orbiting infrastructure to extract resources from space-based sources (e.g. asteroids) using autonomous system which don’t have the complication of having to survive a descent or operate in a dusty environment with variable sunlight. Once that exists, engaging in a crewed interplanetary mission doesn’t required lifting every consumable resource from Earth up to orbit and the mass limits and costs that brings.

Stranger

Great posts all. Ref this snip:

And something to keep said acres of panels dust-free or nearly so. For years.

Can you please explain why splitting water is a necessary step ? In the Chemical Industry, we frequently use electrochemical methods to make high purity Carbon Monoxide (for perfumes and insecticides) from CO2. The other byproduct is oxygen.

Why can’t we have solar cells splitting CO2 on Mars (from my reading there is plenty of CO2 on Mars) ? The CO and O2 can then be combusted in the rockets. Granted CO is heavier than Hydrogen and will reduce payload, but is it totally unfeasible ?

In principle, you could do that. And I suppose that you probably would, if carbon dioxide were the only raw material available. But it’s not actually all that hard to find water on Mars, and hydrogen makes a much better rocket fuel than carbon monoxide.

Or you might use both carbon dioxide and water, and make methane (which isn’t quite as good as a fuel per se, but might be easier to handle). Or many other options. But you have a lot more options with water than without it.

Also keep in mind, of course, that you want to as much as you reasonably can with in-situ materials, and water is also necessary for human life support. We’ll be taking some with us anyway, and recycling as much as we can, but it wouldn’t hurt to have a surplus supply.

And of course, the reason we’d be going to Mars would be to do science, and there’s a lot more interesting science to be done in the places with water than those without.

This may be a bit off-topic, but would it be possible and, if so, efficient to lift a rocket to the upper edge of the atmosphere using helium gas balloons? And once it achieves buoyancy, light the rocket to achieve horizontal velocity? Vacuum engines could be used exclusively, and air resistance would be nil.

You can’t carry your payload THAT high, because you need the atmosphere to be thick enough that the air your balloon displaces weighs more than your own balloon, plus the payload.

Eta: doesn’t mean it hasn’t been tried, though. It just doesn’t save you THAT much weight on the pad.

There are various efforts to use jet-powered cargo airplanes as sort of the “first stage” which will carry the space rocket up to the upper atmosphere, above ballpark 80+% of the drag, and release / launch the rocket starting with typical jet forward speed. Perhaps in a zoom climb to help with the direction of the trajectory as well.

But as Stranger says up in post #46, atmospheric drag isn’t nearly the problem that the gravity well is. And even bigger than the gravity well is the sheer amount of speed needed to gain; that’s the very long pole in this tent.

Jet speed of very roughly 500 mph sounds pretty fast, but compared to the 17,000 mph required for orbit, the jet only gets you about 3% better than a standing start.

As noted in those wiki articles people are trying to make this work for various reasons. See here for more on the general concept:

The question is - how do you calculate the amount of fuel needed to achieve orbit from wherever (even if we ignore air resistance).

It’s obviously not infinite. The answer is - hmmm, I’ll have to drag out my math textbooks and review Calculus. You start with X fuel. the rocket weighs M (so total M+X mass) The engine imparts Z ft-lb or Newtons or whatever of thrust. The rocket burns Y fuel per second. after 1 second, the rocket weighs (M+X-Y) and has accelerated Z/(M+X); next second, weight (M+X-2Y) and velocity ((z/(M+X) + Z/(M+X-Y) and so on. Plus, you need to subtract the reverse force of gravity to start with. There’s a way to convert this to a simpler formula using calculus, but it’s late at night and I need to think about it.

Actually, your progress is a parabolic arch until you reach orbit at the apex, so the force of gravity you are countering is the inclination of your trajectory to earth, and the slope of the parabola is the derivative, etc. etc. There’s a reason they call them rocket scientists.

But - you can see the final velocity is less for a smaller moon/planet, and so the burn time to reach orbital velocity is less, so the total fuel needed is less, so the fuel needed to boost that fuel is less, and the fuel needed to fight gravity is less. So it’s not just “half the gravity, half the size”.

(A rocket engine on earth that cannot even impart 9.81m/s to the craft will not even leave the launch pad.)

Should also point out - the air launch systems are OK, but… They might get you to about 50,000 feet or so, and being subsonic, to 600mph. This may avoid a noticeable amount of air resistance, but at the expense of more trouble. 600mph is nowhere near orbital velocity. You need to figure out how drop the rocket and get the aircraft out of the way, meaning the rocket may fall for a few hundred feet before the engines kick in, thus losing some of the advantage, or has wings, adding launch weight. Not to mention the risk of taking off carrying this huge explosive cargo - or worse yet landing with it, if launch fails. Or dropping it somewhere. Oops. I hope the capsule emergency escape works; and that the aircraft can still fly carrying a rocket with the rocket nose departed.

Chronos posted the Rocket Equation upthread.

@stranger_on_a_train, great to see you!! Could you expound, please, on the current limitations of using parachutes for Mars EDL? Is it a materials issue? A weight-to-drag inefficiency? Reliability?

Hey Chronos - thanks for leading me to this rabbit hole. I stayed up looking at the thermodynamics of water on mars for far more time than I should. It turns out that the thermodynamics is not well understood (at least from the published sources).

CO2 and water does funny things even on earth. We encounter them frequently in natural gas wells. CO2 + Water forms hydrates / calthrates that have weird stability, weird kinetics and are extremely corrosive. With a Martian temperature of -73F and a pressure of 610 Pa (0.09 psi), these hydrates become very interesting.

Whoever is doing the work will be having a fun time figuring out how to stop the rocket from dissolving, or if the rocket will be like mentos in a soda bottle. Needless to say, that even if they find water, it will be saturated with CO2 and maybe more like very very light snow that will have to be shoveled in for any kind of processing. And the snow phases may change daily or seasonally. Lots of fun stuff to figure out.

Thanks again

I can’t see how air launch could ever work for crewed missions.

You need something around the size of the Saturn V to get people to the moon. You cannot make an aircraft that can carry a Saturn V.

You get to have a bit smaller of a rocket because of the savings, but it’s not going to be enough to lower the rocket size to anything remotely reasonable to put on an aircraft.

There may be some use of air launched rockets for small satellites in low earth orbit, but anything beyond that is not going to be be possible, much less practical.