I’ve long had an issue with “spatial reference,” a phrase I think I’ve derived from Hitchcock, meaning “where exactly people are, in relation to other people and things” in films, particularly films of a large scale, such as war movies. I can never figure out what’s going on in war films and must assume a lot that I can’t visualize. For example, if a platoon is supposed to take a hill, I can never visualize that hill’s place in a larger context. Where is the hill, in relation to larger objectives in the battle? How far are the hill’s defensive reinforcements from reaching it? How many soldiers are now defending the hill? Stuff like that. They usually just show the platoon mounting an attack but an attack on what, exactly? Filmmakers just assume you already know this stuff, or that you don’t care, but I do care.

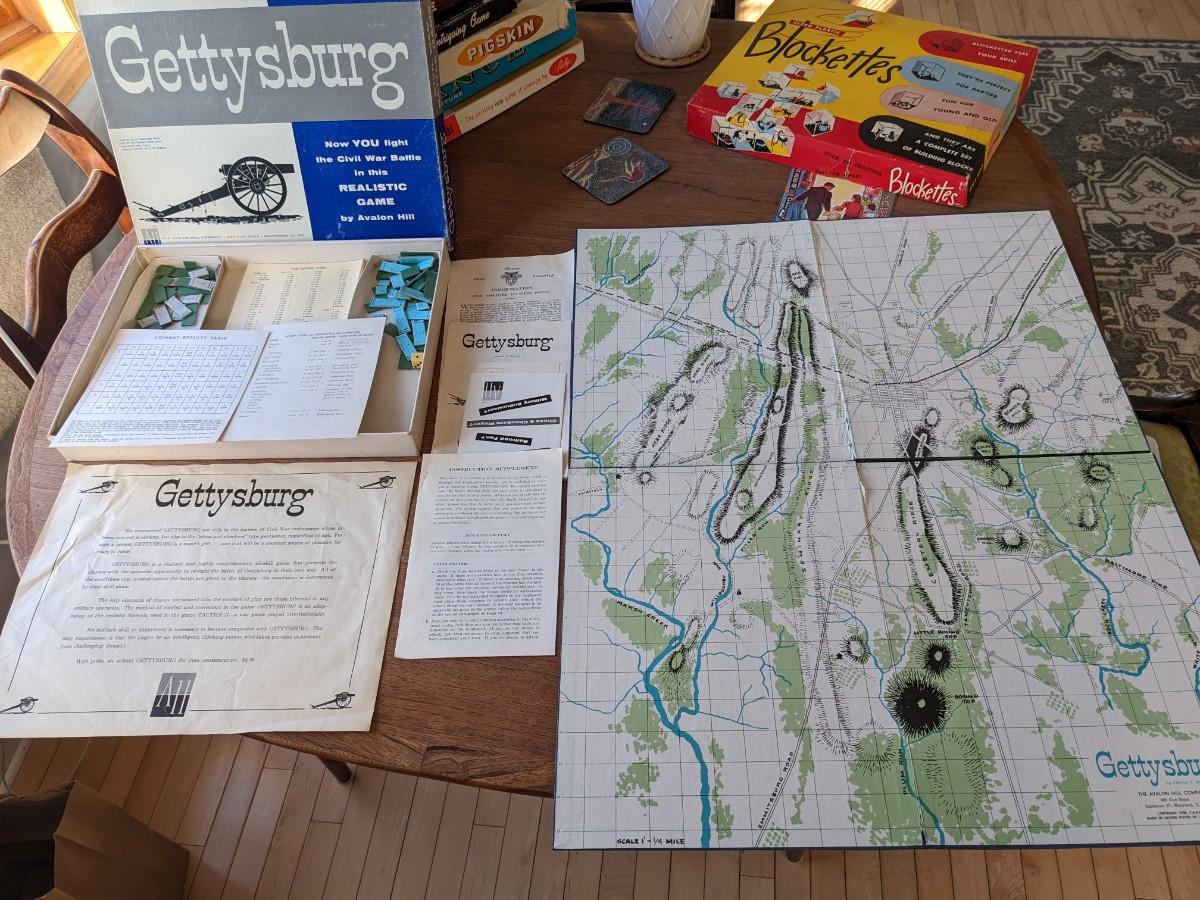

I think I need maps to understand what I’m talking about, but of course films can’t supply any of what I need. I must have seen half a dozen films about Gettysburg, and none of them are very clear about what exactly is going on, mainly because there are about six or fourteen mini-battles taking place within the larger battle, each of which requires its own movie (with maps?) to be understood properly. So I end up taking a lot on faith, and I never really get close to understanding what the hell is going on.

Maybe what I’m saying is that I need some sort of online tutorial that shows where every division, battalion, army and platoon is at every stage of the battle, instead of a movie whose aim is to show a couple of dramatic high points. Is there such a thing?

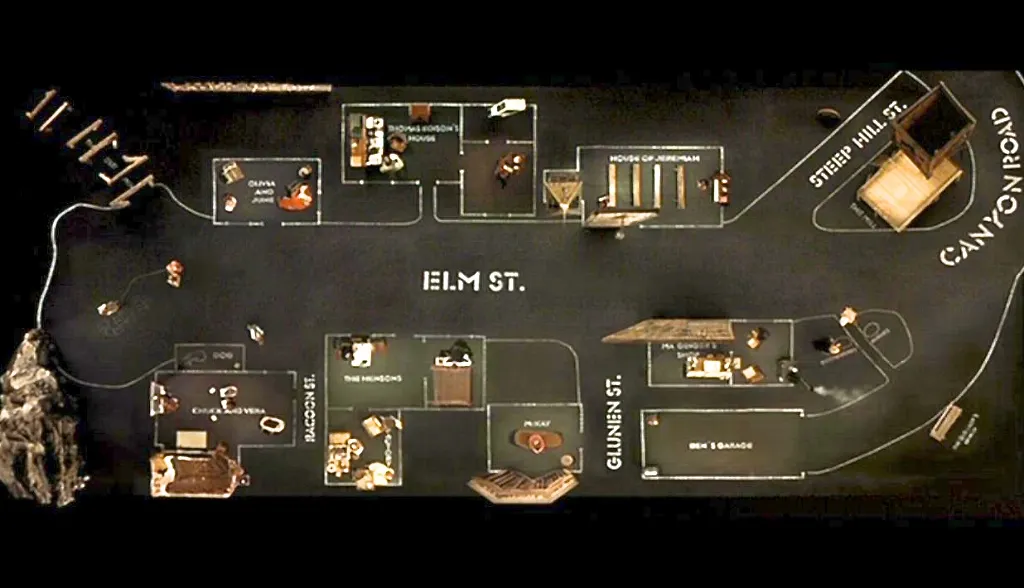

This is only an example of the kind of thing I’m addressing. Really, any war movie does the same thing to me, confusing me and making me wonder where these people are. A larger scope film, like A Bridge Too Far, is simply hopeless, but even non-war movies that take place anywhere outside of a sitting room mix me up. Is this a frequent issue with film directors—do they care if the viewers don’t have a clue where the film is set? How far apart things are is a frequent problem. “I’ll just go there” one character says, and I often wonder, “Okay, how far away is ‘there’?” Walking distance? Hiking distance? Driving distance?

This can be one reason I don’t even enjoy reading novels set in places I don’t know well–the authors assume I have a clue where some town is in relation to another town, and I’m wondering is this like a trip from Seattle to Yakima or more like a trip from Pittsburgh to Tucson. Does anyone else have a similar problem with spatial references?