In case the news was getting you down, this seems promising. What could possibly go wrong?

Deep-seaMiningFAQ.pdf

105.20 KB

In case the news was getting you down, this seems promising. What could possibly go wrong?

People have been talking about deep sea mining for many decades–but it has not gone anywhere because it is not as economic as mining on land. There was a great deal of interest starting in the 1970s with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (which the U.S. didn’t sign and which this article refers to):

Note the U.S. still has exclusive access to a 200 mile Exclusive economic zone

And since it is much shallower than the deep seas, mining is more economic here.

You don’t want to wake the sleeping old ones.

The Economist had a recent bit on this but behind paywall.

Their take, mostly, FWIW, is that there is fairly little to go wrong using the techniques being proposed (essentially Hoovering up spheres of metal that are laying there in areas that are fairly low in biodensity) while the alternatives for mining these metals are relatively known huge things going wrong in impacts. They portray it as low risk of some contained harm vs known larger harms.

I heard it on their podcast. That’s available.

I’ve always found the conversation around this point to be sort of amusing, in a dark and bitter way.

On the one hand, you can say that the market is working. First, we extract the resource from Easy Cheap Locations, and the cost of the resource reflects this. Once that’s empty, we move to More Difficult Locations which were not previously cost-effective, and the market price of the resource rises to reflect the increased extraction cost. Once that’s empty, we move to Very Difficult Locations, with the same rationale and result. At some point the cost and complexity of extraction will be so extreme that the price will be unsustainably high in the market, and we will be forced to adapt somehow to the unavailability of the resource. Basic rules of supply and demand: as long as demand exists at the price point supply is able to provide, the resource will be extracted and consumed.

But I say, Go back to the part where we are efficiently and ruthlessly stripping resources out of reserves in order of least to most difficult, and we all just take for granted that this is how it works — there doesn’t seem to be much interest in rethinking the fundamental “use it up and let the price rise” mindset. It’s one thing to have an expensive resource because it’s scarce; it’s another thing to make a resource expensive because our unsustainable consumption has artificially created the scarcity. Our reflexive acceptance of rising prices as a natural consequence of supply-and-demand mechanics is, to me, a giant begged question in the classical sense, and that big blind spot makes me chuckle.

Yes, of course, there are lots of people talking about sustainability; it’s a common buzzword. But it’s largely treated as a noble end in itself, without much conscious connection to our consumption-oriented market economics. In other words: if the price is going up, think about why that’s happening.

But okay, sure, let’s just install giant mining robots on the seafloor. Yeah, all right, this is fine.

What could possibly go wrong? Oh, nothing that you’d know, or realize, or remember.

The only resource I can think of where the supply is limited to keep the price high is diamonds. Oil seems to be largely controlled by OPEC, but even they only have limited influence.

I guess the problem for basic resources is that if one entity restricts supply, to keep the price up or to ration the product, then others will jump in and undercut them.

If you don’t think deep sea mining has gone anywhere (and I was also under this impression, having somehow missed the Economist report) you might read the link I posted, which says:

Excerpt (from first post)

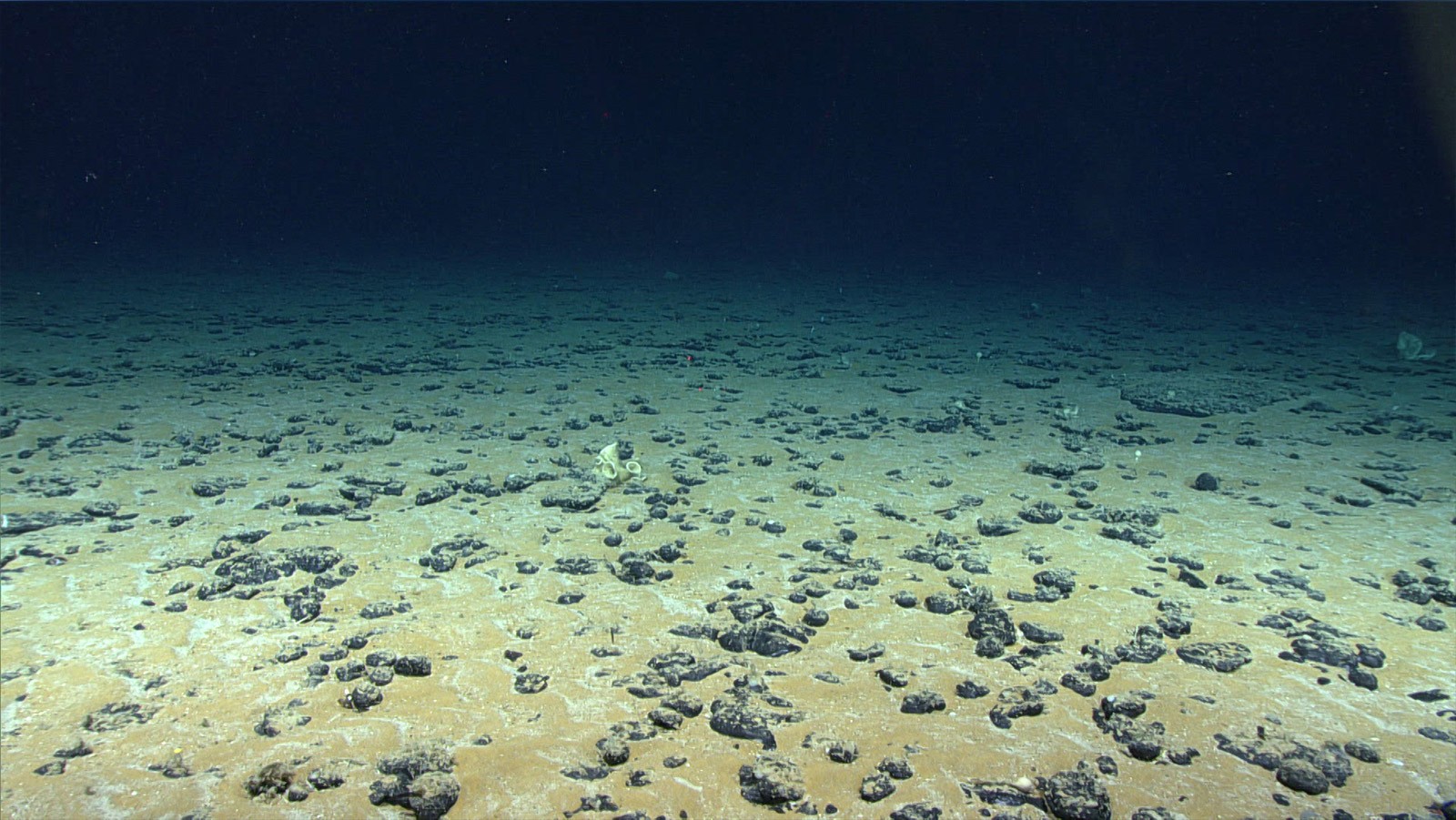

It is China’s latest contract, won in 2019, to explore for “polymetallic nodules,” which are rich in manganese, cobalt, nickel and copper— metals needed for everything from electric cars to advanced weapons systems. They lie temptingly on the ocean floor, just waiting to be hoovered up.

Whether working deep at sea or on land at the headquarters of the United Nations’ seabed regulator here in Kingston, Beijing is striving to get a jump on the burgeoning industry of deep-sea mining.

China already holds five of the 30 exploration licenses that the International Seabed Authority (ISA) has granted to date — the most of any country — in preparation for the start of deep-sea mining as soon as 2025. When that happens, China will have exclusive rights to excavate 92,000 square miles of international seabed — about the size of the United Kingdom — or 17 percent of the total area currently licensed by the ISA.

I’m pretty sure they’re going to reject any bid OceanGate submits.

Google “deep sea biodiversity” and you’ll get a bunch of hits all discussing the striking amount of life down there. Never mind what the would-be resource extractors say about low levels of life there; those depths are actually teeming with an abundance of life forms, and we don’t understand very much about how that biosphere affects ocean life at all levels. The deep sea mining proposed could wreak havoc over wide swathes of the abyssal ocean.

But hey! Never mind that; just rush right in and dredge up the goodies. What could possibly go wrong?

It really does vary much by specific location. Might as well say land diversity and lump Amazon rainforest with a patch of pavement.

The data being evaluated is not provided by the hoped for “miners” btw.

When I was in medical school, some surgeons would cut out knee menisci (very important supporting cartilage) for certain knee problems, or nerves to the stomach for recalcitrant heartburn (not understanding many cases were due to a bacterial infection). Our understanding is now better, and these things are not often done now. I suspect we understand the human body better than the ocean depths. And maybe the ocean depths better than Yog Soggoth.

You forget you’re dealing with suits. They’ll go for the lowest bid. They’re not the ones hurt if the deal collapses.

The Economist had a recent bit on this but behind paywall.

Their take, mostly, FWIW, is that there is fairly little to go wrong

There seem to be quite a lot of people disagreeing with them.

A fairly random selection from the first page of results for “damage caused by deep sea mining” (I haven’t read them all in detail):

105.20 KB

Article by: Jane Marsh, Editor-in-Chief of Environment.co Metals and minerals are an essential part of manufacturing and industry across the board. Everything from agriculture to the latest technologies makes use of precious metals and other...

Est. reading time: 4 minutes

Finland, Germany and Portugal were among the countries that blocked deep sea mining licences.

952.26 KB

To clarify: their main take (presenting various perspectives) was not that there is zero risk of anything of harm. Just relatively very little in context of how these minerals will otherwise be obtained. They argue that that context matters greatly and was unlikely to be considered by policy makers.

To clarify: their main take (presenting various perspectives) was not that there is zero risk of anything of harm. Just relatively very little in context of how these minerals will otherwise be obtained. They argue that that context matters greatly and was unlikely to be considered by policy makers

That is a factor, yes – but part of the problem with deep sea issues is that we understand what’s going on down there even less than we do with what’s going on at or nearer the surface of the earth, so it’s harder to judge how much damage might be done, how much damage actually does get done if we start such mining, or what could be done to ameliorate it.

Humans have a very great tendency to think ‘we know what we’re doing’ right up to, and often for some time after, the point at which it becomes utterly clear that no, we didn’t know what we were doing.

That is an argument for always continuing to do things in a known poor way seems to me. We don’t know for sure what doing something allegedly less harmful might actually do.

I’m not arguing one way or the other myself, do not recall the specifics from the report and don’t care enough to have another listen, but the gist was that the biodensity in the specific region of these spherules was extremely low, the spread of disrupted muck (a big risk) measured as very low, and the known environmental impacts of land mining orders of magnitude greater than even big error bars around them.

The most convincing argument presented against, in my recollection, was that a presumption that deep sea would replace any amount of land mining might be unfounded. It might just be in addition to.