To be fair, they said the same thing (about just wanting to not blow up the pad) about the Falcon Heavy, but that went off without a hitch. Still, managing expectations is nevertheless good. It’s definitely a complex system.

I’d sorta forgotten about their novel stage separation system. Most rockets use springs, pistons, or even small rockets to separate the stages. But they’re trying to just… flip the stages apart. Induce a small rotation and decouple the two, letting them separate with inertia. It sounds tricky.

It isn’t viable for most rockets because the nozzles of the second-stage engines are usually enclosed within an interstage portion attached to the booster. Try to flip that and you’ll just wreck the nozzles–you have to separate them axially. But Starship has enclosed nozzles so they can survive reentry. That means there’s a clean plane of separation–no components straddling the plane that might get banged up. I’m sure they’ve simulated it a bunch, but reality always puts up a few roadblocks…

The Superheavy booster 33 engine test fire is imminent. Maybe within 10-20 mins.

If you want to watch live, here’s the NasaSpaceflight link:

Getting close. The LOX looks to be 100% filled, and the methane maybe 15%. Not sure if they’ll go for more methane; they don’t really need it. But a full LOX load is important for the weight–the clamps aren’t enough to take the full thrust all on their own. Much of the hold-down force is just the weight of the booster.

It worked! The birds were rather surprised.

Wow! I thought all those birds taking off were some sort of debris at first, which shows the scale of the rocket.

Not quite a 33-engine fire:

Still, a record for both number of engines fired (vs. 30 engines on the Soviet N1) and by far the most amount of thrust. And that many engines gives you a lot of engine-out capability.

That was great. However, the fact that one had to be shut down and another shut itself down means they’ve still got some work to do. Yes, they could fly with 31, but two unexpected shutdowns means they still have aome small issues to work out. You don’t want to launch and have four shut down or something.

Still, this is a huge milestone.

It depends on the nature of the shutdown. Remember that every launch is also a quick static fire–the clamps don’t release unless the engines are all working. In that respect, the only point to a standalone static fire is to increase the confidence that the actual launch attempt won’t be scrubbed at T-0:01 (wasting time and money). Once you have confidence in that, there’s no need for a separate static fire (which is what they did for Falcon 9).

Now, if an engine shut down well into the test for poorly-understood reasons, that might be a problem. But if it didn’t complete startup for a ground issue or the like, it may be no big deal.

Yep, could be. But in engineering, any time something happens that wasn’t expected you relly need to understand what hapoened, even if it wasn’t critical. The same failure mode could manifest more dangerously next time.

But as you say, if it’s a simple ground issue or even a manufacturing defect in an engine, that’s a relatively simple fix.

Nice drone view of the test:

Thrust of various rockets:

This test, with 31 engines: 71.3 MN (meganewtons)

Soviet N1: 45.4 MN

Saturn V: 35.1 MN

Certainly, but my point is more about whether the failure is something that would be caught during the pre-launch check of the orbital attempt. If the issue is some minor flakiness in engine startup, perhaps even isolated to one or two specific engines, then there’s probably no need for another static fire. They can just make the orbital attempt, and if it turns out they didn’t fix the issue, they just scrub. There’s no safety issue there. If it’s something more serious, something that wouldn’t have been caught before the clamps release, then they may need another standalone static fire.

I’m just going to leave this here.

TL;DR quote:

Now, with Blue Origin, we’re going as BIG as we can by advancing the dream of running restaurants in space," said Josh Halpern, CEO of Big Chicken

So, fast food chicken outlets in orbit.

More like lame-ass marketing on Earth.

That said… If you want to grow meat in space, Chickens might be what you want. They grow fast, need little space, and can also provide eggs.

Having cleaned chicken coops, however, I don’t want to be in a spaceship full of chickens.

Here’s a fascinating report on chickens:

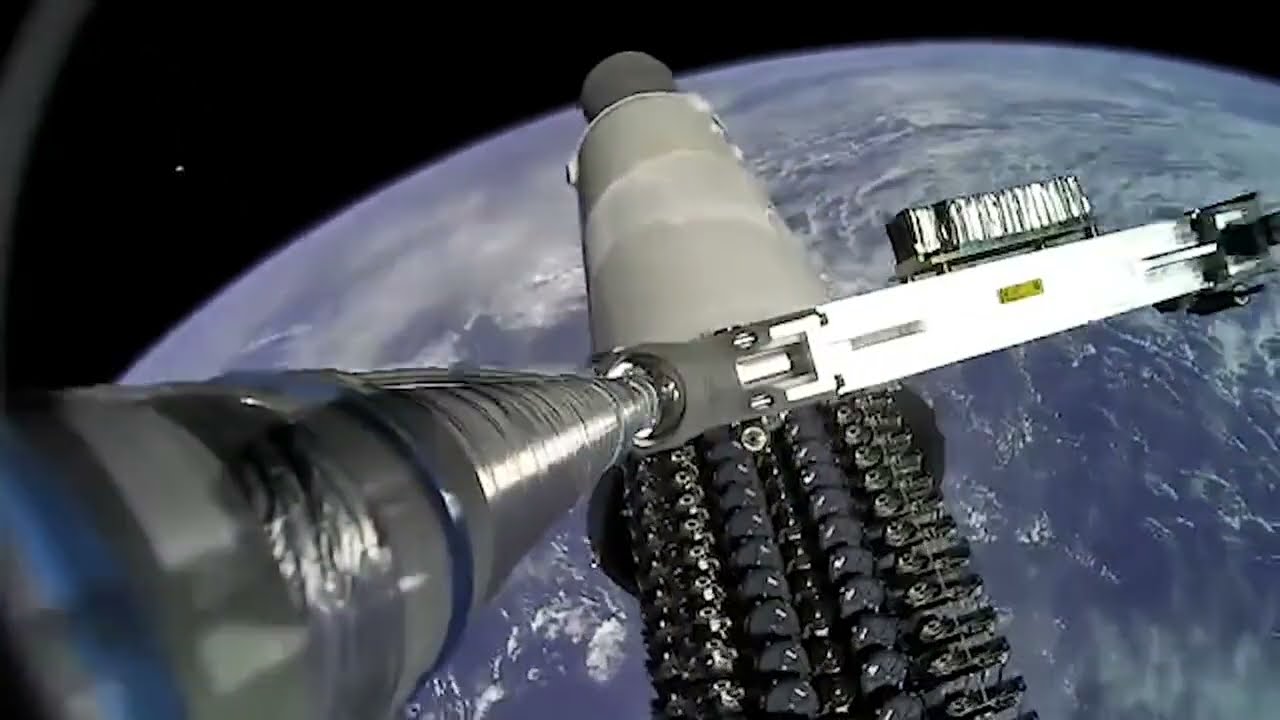

A heck of a picture:

There’s lots of interesting detail in there. You can see the mechanics of the grid-fin actuators, with some stabilization rods attaching to the dome. The two nubs on the left and right are the pins that the booster will be caught on (they look tiny, but the ball on the end is about 7" across, and sticks out about 18"). The mechanism coming from the center bottom is the connection to the upper stage–not currently doing anything, but obviously quite complicated.

The upper dome area is really quite clean and simple. There must be a ton of stuff tucked away.

BTW, this firing was “only” about as powerful as the Saturn V. The engines were throttled to ~50%. I guess they either wanted to minimize pad damage, or maybe couldn’t do more due to the lack of downforce (no Starship and no full methane load). Still, they clearly worked out the bugs with the plumbing and “stage zero”, which were the important bits.

That is a really cool and interesting image, thanks for posting.

A nice vid of the latest Starlink deployment (with the version 2 satellites):

Some things to note:

- The camera is mounted on the retaining rod, which springs backward once released

- The gray cylinder is the stage 2, and the dark cone behind it the engine nozzle

- The corrugated brick thing on the right is a crush pad so that when the rod assembly slams into the rocket, it doesn’t cause much damage. The stage won’t be reused, but it’s important that the stage isn’t punctured or anything.

- The retaining rod is now being retained! Previously, they’d fly off into orbit. Although they come down on their own in months, it’s still good to reduce the amount of debris up there.

- The bottom surface of the satellites is now very shiny. This is a high quality dielectric mirror. Counterintuitively, this makes the satellites very dark (i.e., reduced impact to astronomers). Dark paint isn’t very dark, but aiming the mirror so that it reflects a dark portion of the sky makes them close to invisible.

- The satellites are about 2.5x the size/mass as the previous version, but 4x as capable.

It’s hard to imagine who the buyer would be. The article lays out several options, but none of them make sense to me. I guess one of the old-school players is the best bet, since although Vulcan isn’t a particularly competitive rocket, they will manage to swing a bunch of government contracts, if for no other reason than that they aren’t SpaceX. Blue Origin makes no sense unless New Glenn is truly in an unrecoverable development hell. No way does Apple or Amazon buy them.