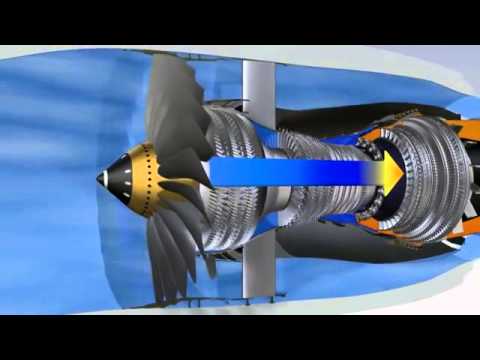

I watched a video of Rolls Royce making their new Trent 1000 Turbofan engine. Absolutely amazing engine. The video claimed the engine ingested 1.2 tons of air per minute at takeoff power. They also claimed most of this air bypassed combustion yet produced the majority of the thrust the engine delivered.

My question; what is the volume of 1.2 tons of air? It seems to me that that is quite a bit.

Here’s a link to the video if you’re interested. (long but interesting)

Wolfram Alpha says it’s 854,000 liters, or a cube 9.486 meters on a side.

ETA: think “house-sized.”

I assume that’s a metric ton or 1200 kilos. Air at STP weighs 1.225 kg per cubic meter. Therefore they’re claiming that the engine moves around 1000 cubic meters of air per minute. (It would be almost exactly the same if that’s a US 1.2 tons or about 2400 pounds.)

There are lots of slippery bits here related to air compression, heating, expansion, etc. but that’s the basic calculation matched to the basic claim.

Nitpick: It is 1.2 tons of air per second (so even more amazing).

You can see how a high by-pass turbofan engine works and why so much power is generated by by-passed air here: Turbofan - Wikipedia

What’s the cross-sectional area of this engine? Three square meters seems like a reasonable engine size, but at that size, the air would need to be going about Mach 1 to get that much flow rate. So presumably this thing is larger.

Yeah, I was fixin’ to say.

Diameter of the fan is 2.85 m. Rolls-Royce Trent 1000 - Wikipedia

So just over 6 square meters.

Thank you for the answers.

So, moving that much air really does produce more thrust than the jet engine itself?

I’m quite impressed with that engine.

OK, so airflow at half Mach. That sounds like the bare edge of plausible, and certainly quite impressive.

Looked at another way, the engine is designed to fly in much thinner air at very roughly M0.75 all day long. If the thing wasn’t able to process all the air coming down its throat, there’d be massive spillage around the outside and that would create massive drag.

So there’s an iterative optimization to match the fan size to the cruise speeds / altitudes. Which in turn drives how much air *could *be processed at low altitude & low speed IF the power section can produce enough torque to suck that much volume. Said another way, they can then keep increasing the power section until it can suck that much air at low speed /altitude.

Once they’ve done that they have an engine right-sized for cruise and maximizing takeoff thrust as well. Real engine design has another 50 factors to balance, but this is a crude outline of some of the biggest parameters in the optimization game.

Add to this 2 challenges : NOx and Sound Levels and it becomes even more amazing.