There were recently two excellent articles in Scientific American (Nov 2024) and Science News (Nov 16, 2024) for the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the discovery of Lucy in Ethiopia. Lucy was ultimately determined to be a 3.2 million year old specimen from a new species, Australopithecus afarensis, which preceded the homo genus. The SciAm article contains a time line that summarizes the current “consensus” of the hominid tree. According to the tree, homo habilis appeared about 2 million years ago. There were several other homo species, sapiens appearing 200000-300000 years ago.

I recall reading some items about the alleged bottleneck for humns in Africa 70,000 or so years ago. While Prothero may want to blame a geological event, It’s also possible that something 'snapped" in evolutionary terms - a new breed of human spread out from Africa, and within 40,000 years had spread acorss the globe (except Polynesia) and basically replaced all other versions of homo. (And occasionally interbreeding with them, considering how humans work…)

While the “new breed” was anatomically close to previous humans, perhaps it was something brain-related. Was it better language? Conceptual thinking? Ability to anticipate and plan better? (Take a hint from what sort of skills disappear with some brain damage or developmental issues, like FASD. Are they indicative of recently evolved brain powers most at risk of being lost?)

Whatever it was, new humans spread out and conquered all, kept going from Capetown to Tasmania to Tierra del Fuego. About 14,000 years ago, give or take, where population density became a problem and terrain permitted, they developed agriculture and/or animal husbandry to sustain larger numbers. This suggests the humans that spread across the globe had the same mental capabilities, yet something better than the earlier subspecies that they replaced who failed to reach that plateau on the hundreds of millenia before them.

As to species differentiation, consider that despite the bilogical distance from southern Chile to Southern Africa or Australia, all those different groups are still quite capable of interbreeding. There is no issue, like for example horses and donkeys or zebras, that the chromosome count or configuration is different. It’s still 23 and me… but 70,000 years, at 25 years per generation, is only 2800 generations. I’m not sure how many generations for species to drift apart. The other major driver of species differentiation is different environmental pressures, but humans instead adapted their environment to themselves, with clothes, fire, building shelters and weapons for hunting. There are only minor adaptations - Inuit, for example, are better insulated with body fat and are able to eat a mainly meat diet. Inhabitants of the high Andes have better adaption to thin air. Inhabitants of the tropics - Africa and Australia - have high levels of melanin for skin protection (or is it the other way around, that it atrophied in those not exposed to strong sunlight?) European males - in hunting parties in cold climates - adapted with thicker facial hair, and according to one theory, male pattern baldness is an adaptation to low levels of sunlight in northern climates, as also is lack of melanin. But none of these differentiate a different species.

Nouns are hardly enough. I would add, at least, verb tenses. Now, if you have, and commonly use, words such as before, after, between, and during, that would do the job without a grammatical structure. But if you have none of that, I do not think you are one of us, even if you have my genes.

Of course, this doesn’t tell us when we arose. It almost tells us there will never be a clear record of when we became us.

Incredibly wrong.

For tens of thousands of years the majority of humans have been mixed race. Neanderthals aren’t “they”, Neanderthals are “we”. I know they are almost universally “othered”, but that is a form of hyperdescent. Neanderthal history is our history.

…

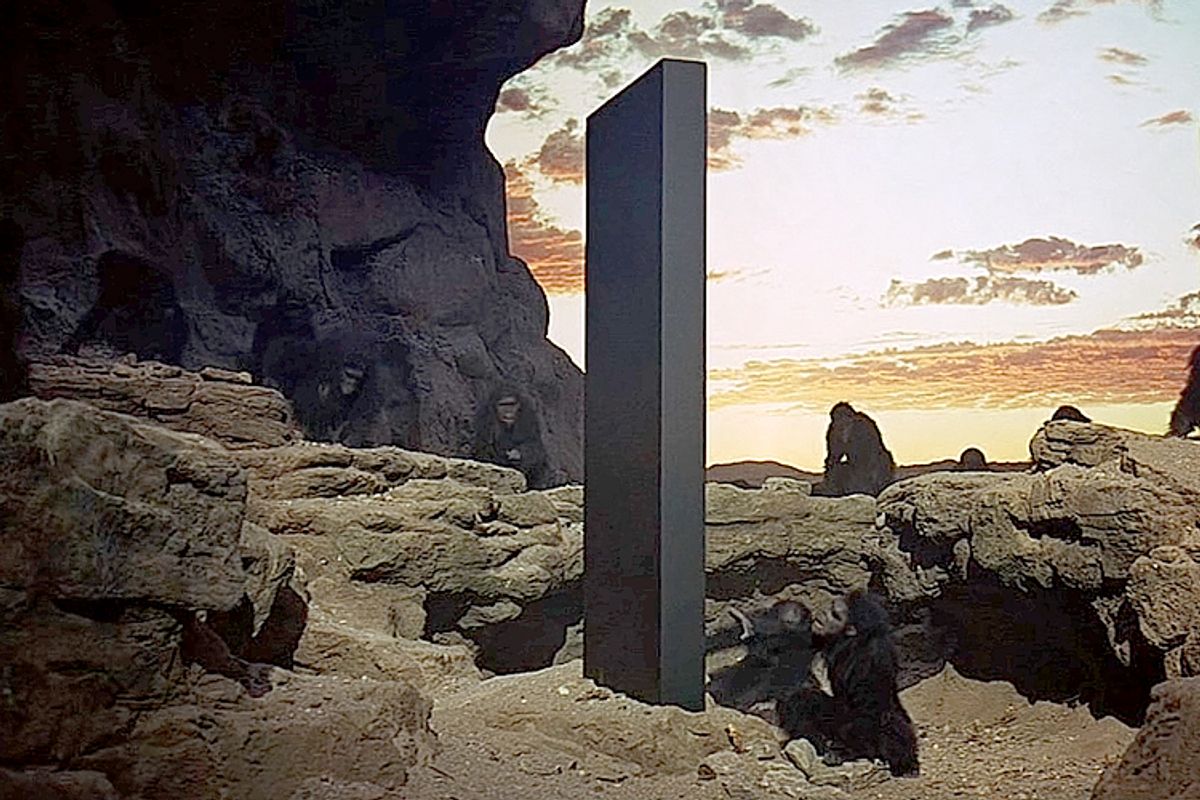

Until we find the obelisk.

And only from around 1800 years ago in North America. The bow is a very useful tool, to be sure, but I don’t think we can generalize from when a particular tool was invented, to when we became the sort of human capable of inventing that tool.

Certainly our direct ancestors outcompeted those other human species, but I’d be hesitant to attach the value judgement “better” to whatever it was. It might be, for instance, that we were more warlike than them.

They’re not in our “line of descent” in the sense that you could say “H. sapiens evolved from H. neanderthalis”, in the same way that you could say that we are descended from A. africanus. A nonnegligible proportion of the modern human population has a few percent of Neanderthal ancestry, and the majority of the modern human population has a negligible percentage of Neanderthal ancestry.

What I’ve read is that anatomically modern humans evolved roughly 300,000 years ago, but that behaviorally modern humans came about about 50,000 years ago.

So the question is “what does ‘humans like us’ mean?”.

The wiki page for Homo shows two reconstructions of lineage, but both put Neanderthals and Sapiens as separate descendants of Heidelbergensis. Denisovians are also their descendants. Probably why both could interbreed with Sapiens.

By the traditional definition of species, that puts Sapiens, Neanderthalis, Denisova, and probably Heidelbergensis in the same species. They could and did interbreed in the wild and produced viable, fertile offspring.

Interbreeding between different species in a genus is well established. The problem is that the products of such hybrids are usually infertile.

Since we know that some Neanderthal genes exist in Sapiens, they must have interbred and the offspring must have been fertile. The question then becomes whether the two are of the same species or whether they’re the rare exception to the “usually infertile” rule, as are the liger and the beefalo.

Prof. Chris Springer of the British Museum of Natural History thinks the answer is the latter.

In the face of this seemingly decisive evidence, why do I cling to my belief that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens are distinct species?

Well, in my view the problem is not with ancient couplings between our ancestors and Neanderthals, but with the limitations of the biological species concept.

We now know from the same kind of genomic research that many other species of mammal interbreed with each other – for example different kinds of baboons (genus Papio), wolves and wild dogs (Canis), bears (Ursus) and large cats (Panthera). In addition, one recent estimate suggests that at least 16% of all bird species interbreed with each other in the wild.

Thus, the problem is not with Neanderthals and modern humans and all the other species that interbreed with each other, but with the biological species concept itself. It is only one of dozens of suggested species concepts, and one that is less useful in the genomic age, with its profuse demonstrations of inter-species mixing. The reality is that in most cases in mammals and birds, species diverge from each other gradually. It may take millions of years for full reproductive isolation to develop, something that clearly had not yet occurred for H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens.

In my view, if Neanderthals and Homo sapiens remained separate long enough to evolve such distinctive skull shapes, pelvises and ear bones, they can be regarded as different species, interbreeding or not.

If you want more rigor, Stringer just published an article in the Evolutionary Journal that lays out his reasoning at copious length.

Measure_for_Measure: I misunderstood your original question. I think by “like us” you meant culturally. “Culturally” is a little fuzzy, but I’d there are several basic components of “culture”: language, art, and tools. (I don’t think numeracy is essential. If a society had language, art, and tools but not sense of numbers, I would say they were “like us.”) Spoken language obviously preceded written language but of course there are no records of it. I would also argue that written language came well after spoken language.

So to answer the questions we just need to answer are what are the oldest occurences of art and tools. From what I can easily determine, the oldest tools are from the Lomekwi site in Kenya dating from 3.3 million years ago. This preceded the emergence of Homo, so tools alone are not a good measure of “like us”.

The earliest occurences of art (cave painting) are much more recent, ~73000 years ago. If we met the responsible individual, would we say they were like us? Maybe, maybe not.

I’d argue there’s one more component of “like us” and that is permanent or semi-permanent human settlements. If we met someone from the oldest known town we probably would say they were “like us”. From what I can easily find, Çatalhöyük founded 9000 years ago in Turkey is considered the oldest. This criterion of course doesn’t do justice to nomadic cultures, but records of these are necessarily sketchy.

The languages of the Chinese language family lack verb tenses along with any other inflections. They don’t show number, gender, case, etc., but still manage to communicate effectively. The distinction I would draw is between languages that have subordinate clauses and (conjectural) ones that don’t. I don’t think there is a human language that lacks them.

And I would not assume that lacking a character to show 0 is going to be any barrier to being human. Before Newton and Leibniz we had no way to write derivatives. Are you going to say before that people were subhuman? I’ll bet I am the only doper who can define the shuffle idempotent. Does that make the rest of you an inferior species?

Since native Australians have a perfectly normal language I will assume they got there with a fully human language. The trouble is, no one can think of a convincing way to pin down when language began. Presumably with a primitive communication system that lacked any real grammar and then one day some genius started using dependent clauses and others picked it up.

As a modern human who likes to live outside towns, even though in a settled form; and even aside from this on behalf of those nomadic cultures, I object to this.

Also – that’s going to be a very blurry line. Nomadic cultures didn’t, or at any rate don’t, wander at random, any more than other mammals do: they travelled primarily around known territories, returning to known sources of food, of water, of shelter at various times of year, during various weather conditions, and/or when the midden started to get too big and/or the food resources too hunted/gathered out. Occasional individuals would have struck out on their own, and groups that for whatever reason couldn’t stay in their territory would have moved elsewhere, sometimes into ground previously unknown to them; but most travel would have been over known routes, and most groups would probably have stayed some time in favorable locations. At just what point would we define such a spot as a settled town? When the people stayed there most of a year? All of a year? Three years at a stretch? Ten?

– admittedly any criteria we use is going to have blurry lines.

I would say that the “people like us” are the people who tell each other stories. Unfortunately, storytelling doesn’t fossilize well; at least, not until we started engraving stories on stone, which may have been a very long time after we started telling them.

I’m not saying that people who don’t live in towns are somehow inferior. Far from it: it takes guts, talent, and inner resources to live outside a town. I’m simply saying that we would recognize someone living in a town 9000 years ago as “like us.” Unless one is entirely self-sufficient, a person relies on other humans for their existence. Whether you call those other humans a town, a settlement, a clan, or just neighbors is immaterial.

I like your stories angle. Yes, we would recognize humans who tell each other stories as “like us.”

I thought I was being careful to make no criticism of humans who may have been very different from us.

That’s been true since long before we were “humans like us.” Most of the other apes live in groups; our ancestors almost certainly did also.

Which clearly includes all the modern nomads. And I suspect it also includes, at a minimum, the people who painted hunting groups on cave walls – I have trouble imagining such paintings not having had stories to go with them; they themselves in a sense are stories presented on stone.

Whether stories go back further than that, I don’t know; and I don’t know how we could tell. And it may well also be a blurry line.

It seems obvious to me; Aboriginal Australians are behaviourally modern humans, and they migrated to that distant location about 65,000 years ago, and presumably took a non-zero number of years to do this - a generous five thousand, probably. That implies that behaviourally modern humans have been around for around 70,000 years, and probably much, much longer.

Anatomically modern humans are much older than that, but they haven’t left much evidence of their culture, apart from the stone toolmaking, which is pretty impressive. We are finding more and more evidence of ancient cultural artifacts all the time.

Art is human enough for me. I expect we’ll find even older examples in due course.

Here’s the Lion Man, an artifact from 35,000 to 41,000 bp. I’ve seen it, and it is majestic.

Humans had already been making art for around 30,000 years by this time.

My take is that if you can invent and use a bow and arrow or undergo an activity of similar ambition then… you’ve reached a certain level of cognitive and cultural development to be “Like us”. By one definition.

It doesn’t have to be a bow and arrow though. The Clovis culture had highly crafted spearpoints of comparable (though still probably less) sophistication than the bow and arrow combo. Constructing boats and fishhooks would be comparable, and there’s some evidence that early Native Americans did exactly that, making their way down the coastline by fishing. Clovis culture dates to 13,000 years ago. Bows and arrows appear to have arrived earlier than 1800 years ago, though they took a while to become widespread. Not a shock, as spears are probably more suited for megafauna than bows and arrows. Wiki on history of archery:

Archery seems to have arrived in the Americas via Alaska, as early as 6000 BC,[27] with the Arctic small tool tradition, about 2500 BC, spreading south into the temperate zones as early as 2000 BC, and was widely known among the indigenous peoples of North America from about 500 AD.[28][29]

There is inherent ambiguity in the “Like us” formulation - which is bad for academic papers but good for a general interest message board. My take is that posters should just define what “Like us” means, then try to track down matching dates.

Anthropologists have described over 3800 distinct cultures: presumably there are many others. In some ways those outside of industrialized Western culture are not “Like us” according to certain definitions, but I expressed a preference for wider concepts in post 2. “Wider concepts” covers a lot of territory though.

There may have been non-trivial cultural and geneflow prior to 50,000 years ago, or so I argued upthread. Furthermore, it’s conceivable that Aboriginal Australians developed cognitively in parallel with the rest of the world from say 50,000 bp to 20,000 bp. We do know that spear technology advanced with the development of spear-throwers aka atlatls. Also boomerangs, the first example of which dates to 9500bp. That said, I think their example is a good one for addressing the OP.

You say nouns, I say terminology. IOW if you have detailed and granular terminology, I’m claiming you probably also have a fair amount of gramatical machinery to go with it.