When Covid first started, there were shortages in toilet paper and hand sanitizer, and there was a brief run on food, but, for the most part, I could get everything else I typically bought. Now every time I go to the supermarket, there are at least 4-5 items I can’t get. I understand the reasons for the supply chain breakdown, but what I can’t understand is why these shortages didn’t start happening a year and a half ago. I put this in FQ because I’m hoping for as many facts as possible, but I don’t mind opinion if the mods don’t.

Even if the supply chain is disrupted, some companies hadn’t gone all in on just-in-time manufacturing, so they had a stock of supplies that they could draw down. That may be less the case for food, but packaging is still part of their supply chain too. Now with shipping containers costing 10x what they used to, some companies are saying “screw it” and simply not restocking because they can’t afford the shipping, sometimes even laying off workers. The ones that can afford the shipping costs are finding that their stuff is stuck at the ports where there’s not enough trucks/trains/trailers/drivers to unload and distribute them. That part of the supply chain breakdown is more recent than the toilet paper shortages of 2020.

It would help to know which specific items you’re talking about because my grocery experience has been sort of the opposite. During the spring and summer of 2020 there were numerous items I couldn’t find at the grocery store, above and beyond the toilet paper and paper towels. Pasta, cleaning supplies, rice, baked beans, cat food, and rubbing alcohol were on my list for months and I could never get some of them. I could usually find something (except the cleaning supplies and rubbing alcohol), but not the brands or types I was used to. Right now the only thing that’s been consistently out of stock that I regularly buy are bamboo shoots. However I have seen some other shelves looking more bare than they did a month or two ago.

Going into the late fall and winter this year, there’s a growing aluminum shortage which is impacting the availability of canned goods, which are already in higher than normal demand due to the pandemic. A poor year for wheat harvest means that pasta may have another shortage. Meat packing plants have reduced processing capacity due to COVID. We’re also in the middle (hopefully close to the end) of another surge of infections that started back in July as the delta variant began to circulate and become dominant. Waning immunity and relaxation of public policies and infection prevention measures have led to more cases and plant closures.

This USA Today article from last month gives a handful of good examples of grocery product issues. A lot of them boil down to one particular component of the supply chain holding everything else up, kind of like with computer chips and cars. Last week I asked a window manufacturer rep what’s the driver for their 24 week lead times (which had previously been more like 8-10 weeks) and it was just one thing, the aluminum spacer bars used to make the insulated glass, which come from China and are stuck in shipping limbo. A lack of foam insulation is holding up appliance manufacturing in a similar way.

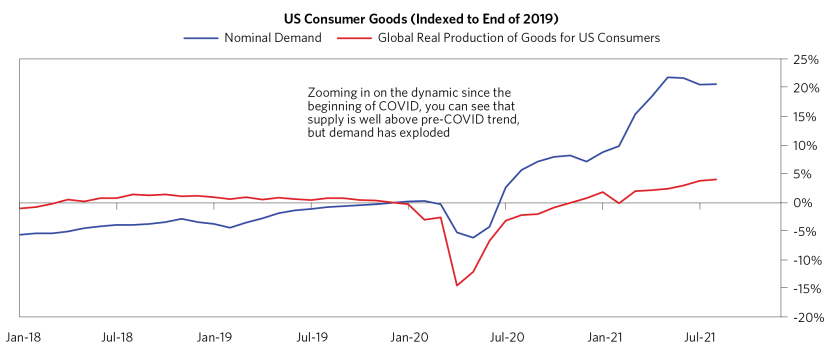

One thing that has changed is that demand is through the roof. You can see it really started exploding around the beginning of this year, when people felt like they could start getting ‘back to normal’ and probably felt more secure in their jobs. Another stimulus round probably helped, but I don’t think it’s the driving factor here.

That coupled with a continuing supply-side shock (not everyone feels safe enough to return to work, some people still have unresolved childcare concerns, major port closures in China, etc) and you get this. The above graph comes from this article:

Which I don’t entirely agree with, but it makes the case that the demand spike is structural and won’t be going away, supply will remain constrained, and we’re in for more shortages and inflation. I’m not endorsing that view, but it’s one of the better articles I’ve seen in the accessible press.

I didn’t read the previous two posts so this may have been said, but a big part of the problem is a lack of truckers and warehouse workers.

I’ve been having tons of problems getting things in and/or getting them in within a reasonable time frame. The reason I’m usually given is that they simply don’t have enough drivers to deliver everything fast enough (or as fast as they used to) and they don’t have enough warehouse workers to load the trucks.

I know some places have made salespeople and drivers help in the warehouse (which I’m always surprised doesn’t lead to a Teamsters strike).

If you look at job listings for truck drivers and warehouse workers, what they’re paying has been steadily increasing over the last year or so.

And this is just for items that are already in domestic warehouses, so not counting things stuck in container ships.

There are also issues of the stuff that is needed to make the stuff that is needed for the stuff can have very long lead times.

We have seen a huge issue in getting high strength steel bars. It used to be an item that many steel mills would produce on spec based on demand forecast and hold in stock then sell.

Lots of mills basically stopped production and have burned though their inventory and are not restocking but only making to order, often with 15-20 week lead times.

Now if you need a small high spec component for a larger device but didn’t think, you are now waiting 15 weeks just to get the material to then make a part that will compete the bigger part. So you get a very linear stacking of lead times that used to be smoothed out because people were stocking inventory. When the fundamental things needed to build stuff from are not available from inventory that can really impact many different items lead times.

At my place, we just ordered a new 16 foot cooler. What should have taken a few weeks, if that, to get in, is going to be something like 16 weeks. And the guy that we placed the order through was surprised it was going to be that fast since some of the other HVAC places have a 6 month lead time.

Part of that, however, is probably due to demand more than supply. Businesses are flush with PPP and EIDL money and doing some upgrades.

There’s been a few products at the grocery store that disappeared early on and have never returned. Typically a particular type of mouthwash, or a brand of ice cream. I still see them if I happen to visit a different grocery store for some odd reason so I know they’re still at least extant.

The high tech industry has basically stopped quoting lead times for components, or they quote 52 weeks and then try to bring in the schedule once there is a PO. Pre-pandemic this was more like 12-16 weeks. Lack of a single component means you can’t finish the truck even though 99.9% of the parts are there.

The high demand for Amazon is having quite the knock on effect. Amazon warehouse and delivery workers tend to make more than minimum wage service jobs or low end gig economy, have better or more flexible hours, some benefits, etc. This has sucked a tremendous amount of low end workers out of the previous jobs.

Nobel prize winning economist Paul Krugman today wrote that the spiking inflation is demand driven, and most akin to the post WW2 1946-1947 inflationary period. Then it was demand driven and the supply chain was constrained as it switched from a war footing to consumer focused.

Our dishwasher died and we were shopping for a new one recently. Lead times are now months, nobody has ready stock. Talking to the salesman, one of the problems they have (weirdly) is storage expenses. They supply appliances for new construction. A shortage of some items means they have to store huge amounts of partial orders waiting for completion. Nobody wants to build a condo and have the refrigerators delivered now, the stoves in a few weeks, and the diskwashers later still. Even trivial problems - they can’t deliver stoves because they are waiting on a shortage of the junction boxes to connect the stoves to electrical. They don’t want the situation where the stove is delivered but not connected, then the electricians have to make repeat visits.

I assume we saw the supply chain being drained for the first few months. Our salesman was trying to have an appliance shipped in from a Calgary branch, then Vancouver, with no luck.

Also, those ports were working full time before the pandemic. Shut down or slow down due to Covid cases, and the ships en route are now sitting offshore waiting. Getting caught up is a problem with the same issues affecting truckers and the railroads and the more local distributions. getting caught up is not just a matter of working overtime a few days, a multi-month backlog will take even longer to work out. News reports also blame a shortage of containers, since shipping PPE to places like the third world has left a lot of containers in places they are rarely retrieved from. And, naturally, there’s Covid shutdowns affecting the factories themselves, often erratically. Much of the supply system has strong interdependencies and we are seeing the cascade effects of some failures.

My favorite soft drink is Diet Mountain Dew, which is almost impossible to find lately. A store rep I asked said the problem was supply of aluminum cans. This is another issue - that widget from China also won’t ship if the plastic wrap or carboard packaging is in short supply. Interdependencies.

It’s not new. When there were floods in Thailand a few years ago, it took out some of the major factories making computer hard drives. For a few months, hard drives were hard to find. For today, multiply that sort of thing by the whole economy.

Not to take anything away from any of the factors previously cited, but I wonder if an additonal component is the hope/expectation/predictions that inflation will be transitory.

Suppose you’re a manufacturer and need a certain key component of something and prices for that have gone up 400%. If you thought OK, that’s the new normal, then you keep buying as usual and just adjust your selling price. But if you think that prices might soon return to something close to pre-pandemic prices, then you would be tempted to buy the bare minimum and hope by the time you need more prices will be down. Then, if you get more orders than expected (or have problems with a shipment), you’re out of stock.

Amazon is cited as another culprit. Amazon sales are up a lot. (Similarly, Home Depot and other hardware vendors). The thought is that rather than dining out and travelling, people who still had jobs had disposable cash to use on those toys etc. from Amazon, or to do pricier home renovations. So some items are seeing a spike in demand, just when the shipping can’t keep up and the factories in the far east are having issues with Covid.

I think this is correct too - this strategy has finally caught up with the supply chain, and all “fat” in the system - extra inventory around the country - has been fully depleted. The engine has been running faster than we can pump gas and the tank is now empty.

First of all I’m not sure that this should be in Factual Questions at all, since the answer is very much a matter of opinion. That graph seems particularly controversial and downright inexplicable. Granted, there are supply-side constraints, but supply in general has been climbing above pre-COVID levels, as seen in that graph. So why do we suddenly have all kinds of shortages? From the random and temporary nature of the shortages I’m seeing, I’d attribute it largely to transportation issues, and occasional production issues, all of which have been well documented.

That article, however, wants to place the blame squarely on “MP3”. Note that this is an investment site, run by Ray Dalio, the founder of one of the world’s largest hedge funds. Hence, hardly impartial with regard to matters like government spending and taxation. Note also that “MP3” here (no, not a music format!) stands for Monetary Policy 3 and attempts to implicate the policy of economic stimulus payments as the major cause for the surge in demand, as if all those formerly poor and newly jobless people are suddenly surging out and buying up the world. I doubt that those stimulus checks are buying much more than just food for their kids.

Agreed that FQ is not the right place for this. The topic is too deep and controversial for factual answers.

And demand is through the roof, which is the point of the graph and the article. Most of what are being perceived as supply-side choke points are actually supplying at all-time high-levels. Chip manufacturing, throughput at ports, etc. They just aren’t supplying enough to meet current demand.

Where I think I differ from the article is in the degree to which that demand spike is temporary, which can be from either pent-up demand during the pandemic, or a shift of demand from services (eg, some people still don’t feel safe enough to travel or eat out, so they’re spending their money on goods instead.) The article posits that it’s a permanent new level of demand driven by MP3. I don’t think that’s proven. (Nor, it’s worth pointing out, in Bridgewater/Dalio’s other work, does he necessarily paint MP3 as bad.)

That’s all starting to get a little far from the thread. The part that I think is relatively factual and material to the question at hand, though, is that demand for goods is at an all-time high. That’s at least a factor in the shortages we’re seeing.

Are you forgetting that the poor have the highest propensity to spend? That’s been the basis of the whole theory of redistributive ‘stimulus’.

There was a big difference between earlier forms of quantitative easing, which basically went to banks to shore up liquidity and didn’t move around the economy much, and the covid-era ‘stimulus’, which basically helicopter-dropped trillions of dollars of printed money on the population to spend.

The money went out when people were locked down and unable to spend much. Now that things are easing, that printed money is flooding into the market, competing for the same goods and services. Some inflation from that was inevitable from first principles.

The question is really how much of the inflation is due to permanent monetary factors vs temporary supply chain issues. It’s a mix of both, and the ratios are not clear.

That’s basically right, Sam, but the piece you’re glossing over is that even if you helicopter drop trillions of dollars on the population to spend, if there’s sufficient slack in the system, you won’t get inflation as a result. It’s super simplified, but if you think of inflation as the old saw, “too much money chasing after too few goods,” but if you increase the goods at the same rate you increase the money, you don’t get inflation. And all the evidence prior to March 2020 was that there was plenty of slack in the system for mass-manufactured goods. And all the post-March 2020 evidence is subject to debates around how long-term those effects are versus subsiding once the pandemic is truly, globally brought under control.