That’s an interesting explanation, though it doesn’t explain Greek & Roman scripts, where it’s only S that has a final form, and only in lowercase.

there may have been other letters once upon a time, and no texts come down to us. I dunno. Not married to the theory, just thinking out loud.

I’m doing a detailed catalog of my collection and I’m still mad at Marvin Kitman for titling his book on George Washington The Making of the Preſident, 1789.

But the long s is still an s. It’s not a different letter. It’s a different glyph for s. Its like the difference between an upright s and an italic s. At least in modern orthography.

So what’s the issue? Catalog it under The Making of the President, 1789 and be done.

ISTM the final/isolated forms are the original forms, whereas the non-final forms are ligatures, as it were.

I did, but I had to hunt down a medial s to enter it into the notes.

My dad mentioned once seeing an olde english recipe on How to cook a suckling pig. Or maybe it was a sucking pig..

No, I think a suckling pig is a small piglet, still young enough to be suckled by its mother.

Exactly.

Given you out this in this thread, are you sure it was a sucking pig?

As recently as about 1950, the Penn alumni magazine was still titled “The Pennfylvania Gazette” (or so it looked to me). By the time I received it in the '60s it had changed.

Yes, the integral sign is a modified version of the long s, but the sum sign is a capital Greek sigma \sum.

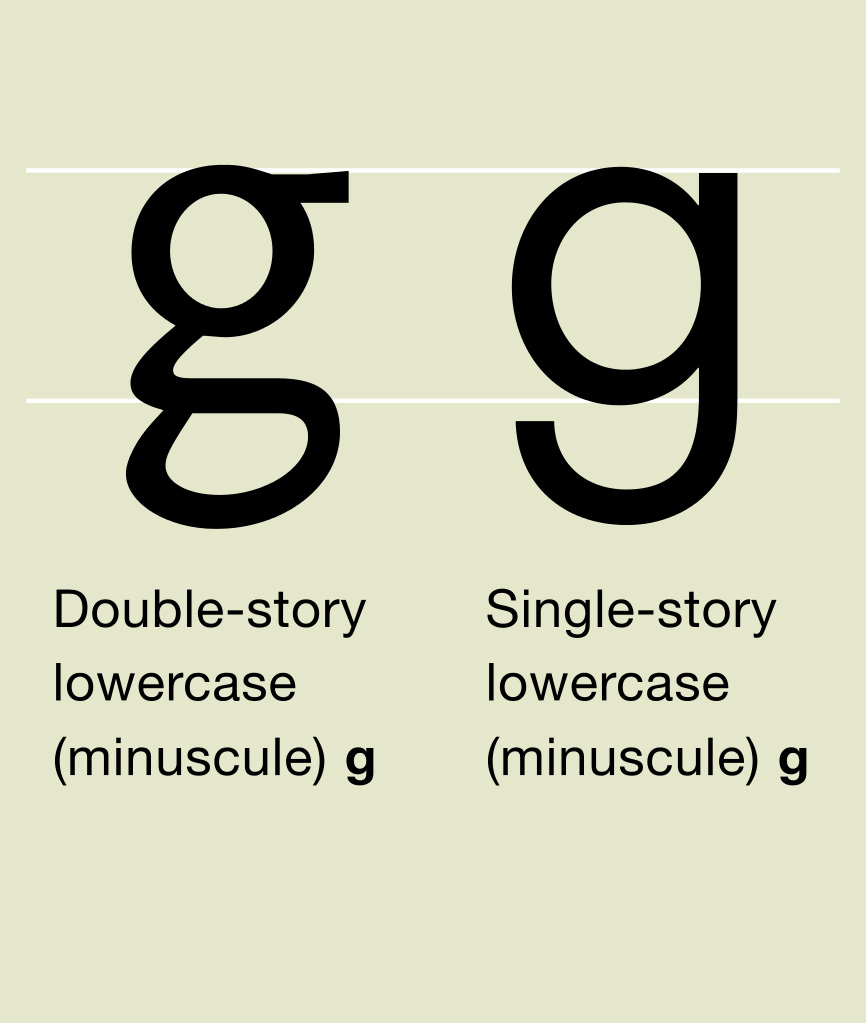

How many of you ever notice that the roman a is shaped entirely differently from the italic a? I wonder whether people in the 18th century even noticed that there were two different shapes for the s.

Looking at this after I wrote it made me realize that the so-called italic font used here is not italic at all, simply slanted roman, not the same thing at all.

Aka “oblique.”

ɑ

Is what you’re looking for.

Depends what you mean by ‘noticed’. Most people who could write were fully aware that ‘s’ had two different forms and they knew how to use them, because the most common forms of handwriting used both. But, then and now, we don’t usually pay any conscious attention to letter forms when writing or reading. Read enough books printed before the nineteenth century and you quickly just accept long s’s, in exactly the same way you just accept the forms of all the other letters.

Yes, that was the a I was looking for. Until it was pointed out to me, I was not even aware that there were two different a shapes.

I knew about g, but I needed only one example. The point is that you can unaware of the two different shapes until it is pointed out. Also the difference between the two kinds of a is starker.

Cursive forms can get even more bizarre. I make my printed “a”s double decker style most of the time, so I noticed that one early on.

My opinion (backed by a total lack of evidence that I’m aware of) is that printers are to blame – dropping the second form of ‘s’ gave them more room in their job cases, and simplified both setting and breaking down type.