I think that particular phenomenon you mention (of blues and greens not always being differentiated) is a natural result of their closeness in wavelength on the visual spectrum:

You can see how blue just fades into green there. “Light” and “dark” in this case isn’t a separate grouping, but just the intensity of that particular light source / reflected light. The result is that different cultures will draw those lines differently, naming the same fundamental colors from our shared biology (which is more sensitive to some wavelengths over others) but then dividing it up after that somewhat arbitrarily, at least until modern times. Early research was documented in the book Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution. I think latter research has challenged some of those findings and painted a more complex picture, but the overall idea that “color names are cultural” is still applicable.

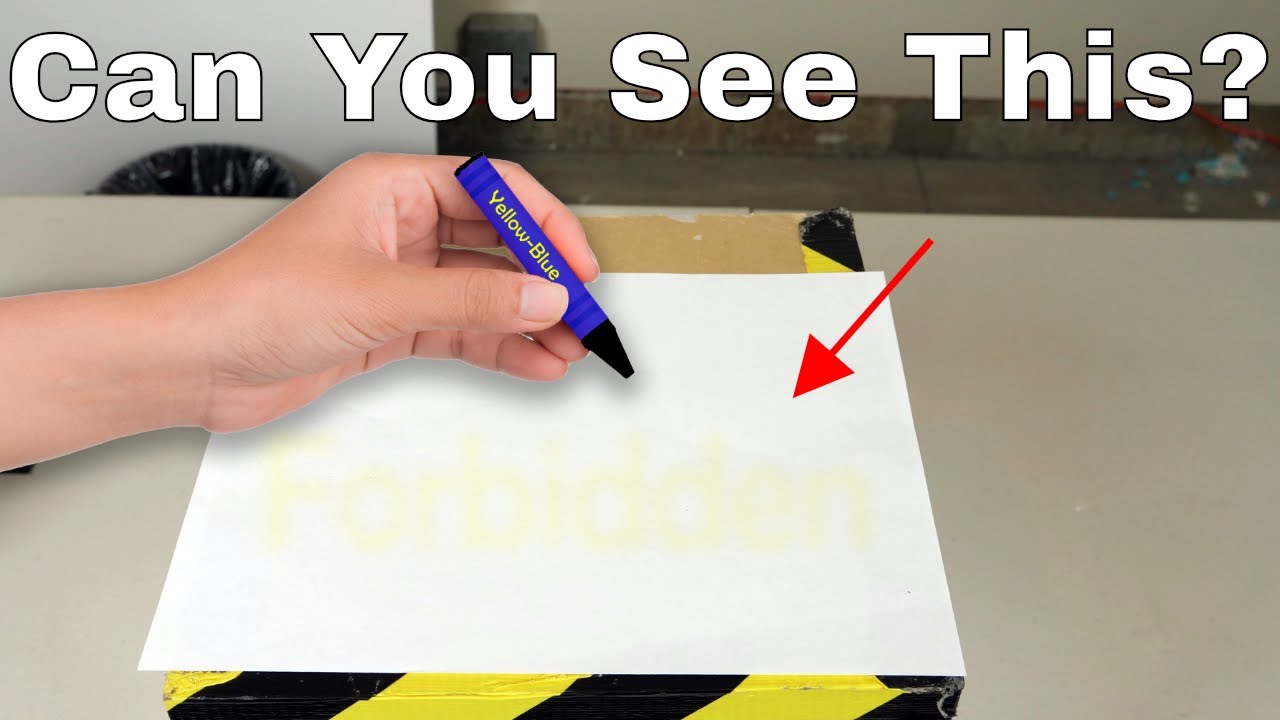

More specifically, that means that within any culture, if they don’t use the same groupings as English speakers do, their (old) words for colors might look like they’re “jumping the gap” to us, but that’s just a translation thing, not anything inherent to the spectrum or their biology. Our word for “orange”, for example, might’ve been some variation of “yellow-red” in older cultures. That doesn’t mean they’re jumping the gap from red to yellow and back, it just means that like blue-green, orange is naturally in between. Similarly, even though we have a distinct word for “brown”, it’s really just dark orange. Most color names predate our modern understanding of the visible light spectrum, and so are named after fruits, dyes, plants, and various other natural things we happened to see in a given environment.

Below the layer of languages, fundamentally the way we sense color is due to how the color-sensing organs in your eyes work – certain types of cones in your eyes are most sensitive to reddish, blueish, and greenish, unless you’re one of the few people lucky enough to have the mutation for tetrachromacy and super color vision, able to see 100x more colors than we can (though they probably don’t have names for the other 99 million…).

So I think what you’re describing is likely just the result of cross-cultural color translations, rather than anything inherent to the various color systems in use. Regardless of the names, they all basically boil down to the physical properties of the light of our sun, filtered through Earth’s atmosphere, and how our eyes evolution accordingly to sense the remaining wavelengths. Different animals (and some mutant people, above) will see different parts of the spectrum, including into the infrared and ultraviolet (and we can too, with special cameras and imagers).