He outlines all of that, and its relationship to scales and chords and consonances and dissonances, in his book, even as he throws out a big fat disclaimer that he does not know anything for sure about whatever is the underlying true physiological basis of harmony in the hearing and the brain.

However, if I have understood something about the history, to grossly simplify things, once upon a time intervals like 3rds (tuned in various ways) were considered dissonant and irrational, however later styles changed. As another example, parallel fifths and fourths were OK, but later they were not.

Schoenberg mentions “unusual scales” of other cultures, among other things, as evidence that the history of what dissonances have actually been selected in practice hardly leads to a correct judgement of the real relations, because the “unusual scales” (including microtonal scales) must be just as natural, and their tones are often more naturally tuned than those of a tempered scale.

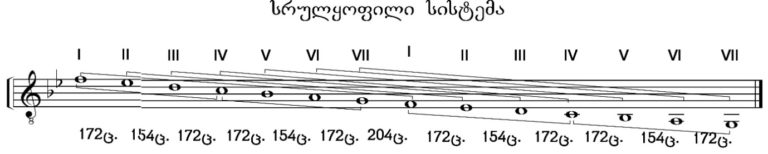

Now, you are asking about traditional scales that do not incorporate the octave; that is an interesting question. I am no ethnomusicologist, unfortunately. Some music is not polyphonic at all, for starters, which would affect how you might tune your instrument. Another thing to consider are traditions such as Ancient Greek, Georgian, etc. which are based on perfect fifths and quartal/quintal harmony. If you do a little arithmetic, you can see that perfect fifths do not combine into octaves.

Many are, but, especially if you admit “experimental” scales, there are plenty of examples of things like the Bohlen-Pierce scale (3:1 instead of 2:1). However, as mentioned, even if you do start from an octave, dividing it equally is arguably less traditional than not doing so.

The thing about limitations of instruments is that, maybe not so much with a violin, but if you want to play arbitrary microtones on a keyboard instrument like a piano or harpsichord you quickly run into the problem of requiring lots of keys, and the resulting instrument being rare and expensive. Certainly in the 19th century, but even today when it is trivial to produce any pitch and any timbre to any level of precision, for example via digital synthesis, how many musicians are trained on it?