My Japanese prof used to refer to “keeping up with the Tanakas” as Tanaka is supposedly as common a family name over there as Smith or Jones is in the States.

I went to school with a pair of sisters named Autumn and Summer (80s).

Oh yes, I agree. But not quite in the same way that you have in English where people choose a different variant just to be different. One of my friends gave his son a name in katakana with no Kanji which surprised me. His other sons have more common Japanese names.

That type of writing is commonly know as Furigana (Furigana - Wikipedia) and as you note is common for all types of works for young readers, both in Manga and picture books. It is also common in language learning materials. A number of Japanese learning apps I have seen have that as an option when learning vocabulary.

//i\\

Thank you all for your replies. This thread has been very educational.

This is what I was getting at. Murakami typically describes conversations between two characters about which kanji are used in a name. It strikes me as an American as odd (just like it would seem odd if an English novel had two characters talk about how one of them spells Cindy / Cindi / Sindee / etc., unless there was some specific plot point about the spelling), but it makes sense now with all the replies you all have posted.

From Anne of Green Gables:

“Unromantic fiddlesticks!” said the unsympathetic Marilla. “Anne is a real good plain sensible name. You’ve no need to be ashamed of it.”

“Oh, I’m not ashamed of it,” explained Anne, “only I like Cordelia better. I’ve always imagined that my name was Cordelia—at least, I always have of late years. When I was young I used to imagine it was Geraldine, but I like Cordelia better now. But if you call me Anne please call me Anne spelled with an E.”

“What difference does it make how it’s spelled?” asked Marilla with another rusty smile as she picked up the teapot.

“Oh, it makes such a difference. It looks so much nicer. When you hear a name pronounced can’t you always see it in your mind, just as if it was printed out? I can; and A-n-n looks dreadful, but A-n-n-e looks so much more distinguished. If you’ll only call me Anne spelled with an E I shall try to reconcile myself to not being called Cordelia.”

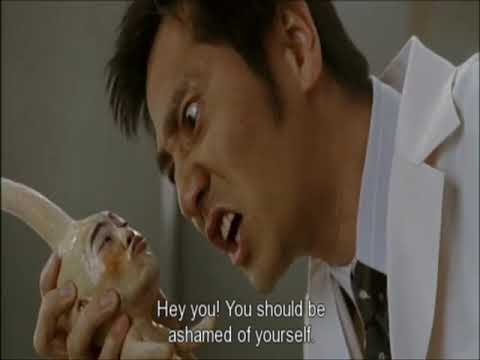

One of my favorite Japanese movies is Naisu no Mori (titled–unfortunately–Funky Forest in English) which consists of a number of dreams. Similar in concept to the Kurosawa movie Yume/Dreams except batshit insane. In one scene a guy is attempting to shame a creature. At one point (around 5 and a half minutes into this clip) he mocks it for gaving the very ordinary name “Yamada”.

Names arer different here in Japan so it’s not the same was as in English, but people give kirikira names to their kids, as I posted a link above.

Having names in either hiragana or katakana is actually quite common these days.

Yeah, that’s part of the process.

There are a few really common names, including Tanaka 田中, Suzuki 鈴木 and Yamada 山田.

You often see name such as Yamada Taro 山田太郎 or Suzuki 鈴木花子 used as examples of filling out paperwork like John or Jane Doe. Hanako used to be more popular but not so much these days.

I assume you are talking about given names. Do Japanese today have family names like westerners, and do they come after the given name?

Sorry, I wasn’t clear.

This part of my post is referring to family names:

And this refers to both family names and given names.

Added “Hanako” in the correct place in the example.

The family name comes first and the given name follows. For the first case, Yamada Taro 山田太郎, Yamada is the family name and Taro (a typical male name) is the given name. For Suzuki Hanako 鈴木花子, Suzuki is the family name and Hanako (previously a very typical female name but dated now) is the given name.

After Japan opened up to the West, Japanese typically reversed the order of their names when referring to them in Western languages.

People write them in the normal order (family name followed by given name) in Japanese and then reverse this when writing the romaji, to transliterate names.

Refer to the wiki article on the famed Japanese WWII admiral Yamamoto:

The order given in English has been reversed to the Japanese order, which is seen with the kanji and then the following romaji.

In contrast, Chinese names for people from China, Taiwan, etc. retain their original order even when romanized.

I always think of the Pharoh Narmer as “Catfish Chisel” because of his ideograms. Now I’m probably stuck thinking of Yamamoto as “Mountain Book Fifty-six”.

Just to add that this is all broadly the same in Chinese, given the shared origins of their written form, and that, like Japanese, Chinese has few unique spoken sounds (though I can’t vouch for all dialects*).

So, if you’re introducing yourself to someone in China, and say your name is gaosi, you would typically then say “Gao as in Gaoji, si as in sixiang”, say, so that they know the characters are 高思, and not, say, 糕斯, which would be pronounced exactly the same.

* (background about Chinese for those interested)

A number of different “dialects” are spoken in China: Mandarin, Cantonese, Min, Wu etc. Their spoken forms can be as different as English is to, say, German. But they are only called dialects, and not languages, because the written form is the same.

FYI Mandarin is the spoken lingua franca across most of China, and the written form already is a lingua franca.

Japanese is almost another dialect in this sense, because Japanese Kanji overlaps considerably with Chinese Hanzi, so, for example. I am able to read a lot of Japanese writing despite not speaking a word of Japanese. Almost but not quite a dialect, because some 30% of Kanji characters have diverged from the Chinese, and Chinese has no equivalent to the phonetic Japanese scripts (no equivalent apart from the Romanized text, that is).

For Japanese kanji, there are the “native readings” (kun-yomi) and the reading based on the original Chinese at the time the kanji were borrowed (on-yomi), although some changes have occurred.

The native readings are the native Japanese words for the particular kanji. For example, for the kanji 林, woods, the native reading is hayashi and the on-yomi is rin. Family names tend to have native readings, and there are fewer homonyms with family names.

Responding to the question concerning Chinese.

Summary

I know you put the qualifier as "almost but no, that stretches the definition of dialect too far. They come from two completely separate language families and the grammar of the two is completely different.

I read Japanese so I can understand a certain amount of Chinese, but speakers of either languages can’t simply pick up a novel and get enough of a meaning to say that Japanese is even remotely considered a dialect of Chinese.

Certainly, I’m able to get around in Taiwan, read menus, take trains, etc., just using Japanese, but this does not mean that Japanese is almost a dialect of Chinese.

Continuing the Chinese-Japanese convo:

I once spent a couple days knocking around Tokyo with an American friend who reads some Chinese. He was able to read signs well enough to say, “hey, want to try that noodle shop?” And also read menus pretty accurately. But he couldn’t speak any Japanese at all.

More

Menus and shop names are among the easiest things read. Novels, not so much.

Tanaka is the 4th most common family name, so the same tier as “Brown” in both the US and UK by ranking (approx. 1% of the population, though Brown is about 0.5%).

The “Smith” of Japan is Satō.

It’s interesting because although the most common last name is Satō, the typical names used as John or Jane Doe tend to be the ones I mentioned above, Tanaka, Suzuki and Yamada, although sometimes governments will use the name of the prefecture or ward (city) in Tokyo, for example. I’m not sure why Satoh is getting dissed.

Japan has a very large number of surnames (10s of thousands) compared to other cultures. Possibly more than any other culture. The reason is that surnames were introduced, for the general population, only very recently, in the late 19th century.

Some time ago I saw a YouTube video about how the number of surnames in a culture decreases over time, in the limit approaching 3 surnames for the whole population after many centuries. Something like this has happened in Korea, which has a much older surname culture than Japan and consequently much fewer surnames, with most Koreans having one of 3 surnames.

Isn’t there a naming tradition that basically translates to “X Son” in one reading but also has a different metaphorical meaning?

Ichiro, Taro, Jiro etc.

According to the Wiki article I linked to above, it looks like there are more total numbers, although I’m not sure exactly how many of these are considered “common.”

Although there are a larget number of surnames, they are mostly combinations of a subset of characters used in surnames.

In this list of the 100 most common names, 95 of the names have two characters, two names of three characters and three have only one character. However, out of the 199 characters used, ChatAT counts only 81 unique characters.

Most of the character have a single kun-yomi (native reading) when used for surnames. For example, 林 has the (native reading) of hayashi, and the on-yomi of rin is not used on surnames. Some of the character change pronunication according to fixed phonetic rules or convention. 小林 is kobayashi where h changes to b.

There are a few names that can have a couple of common pronunications for the same set of characters such as 渡部 that can be read as either Watabe or Watanabe. Another character 辺 is more commonly used for Watanabe, 渡辺. This is quite rare.

Some characters such as 小 small, can either be read as o or ko such as in 小川 Ogawa or 小林 Kobayashi.

Surnames are much easier to read and they are much less complicated than given names.

This is interesting. I did some research online.

Wiki says about the three surnames account for half of Koreans.

Looking at Chinese names:

Back to Japanese names, as the vast majority of Japanese women take their husband’s names when they get married, the vast majority of children have the father’s family name and fewer and fewer children are being born, this number will certainly descrease as time goes along.

Yes. This is right. Japanese care much more about the birth order, and people often discuss their children using “First son”, “Second son”, “First Daughter” and “Second daughter” although I get the sense that this is fading somewhat.

As the number of children is currently something like 1.26, people when to say “my child”, “the older sister” or “younger brother” , etc.

There are some names associated with the oldest brother, including 一 ichi or kazu number one such as 一郎 Ichiro and 太郎 Taro. Similarly, some names are associated with second sons such as 次郎 Jiro (next son) or 二朗 Jiro.

I had a girlfriend who was one of eight girls in her family. Her name was Motoko (another girl) and she had a sister Tsugiko (Next girl).

This tradition seems to be not as common as previously.

Right, so, how many people/how difficult is it to change one’s name officially on the grounds of it being lame, embarrassing, having an inauspicious stroke count, or any other reason for not wanting to have it written down all the time? [And, incidentally, how easy is it to get rare and/or genuinely original kanji approved?]