I’ve been reading some of Haruki Murakami’s books recently, and one of the things that strikes me is that some times there will be a mention of how someone’s name is spelled. It might be about how two names sound the same but are spelled differently, or how the spelling is the same except for one syllable, or something else similar. Does the way a name is spelled in Japanese have some significance that it doesn’t in English? There’s nothing, AFAIK, that would make two brothers being named Edward and Edgar, or Robert and Roger, be any more significant than if they were named David and Howard. But from what I gather, that kind of naming might mean something in Japanese. What’s the straight dope on this?

This isn’t necessarily going to answer your question. But just to add some context, there is a very loose relationship between how Japanese names are written and how they are pronounced. Two names can be pronounced exactly the same, but written with different characters, while two names can be written with the same characters, but pronounced completely differently. This has the effect that if you see someone’s name written, you may have no way to tell (literally, no way) how the name is pronounced, unless they tell you. Similarly, if someone tells you their name, you can’t know for sure how it’s written unless they tell you what characters they use to write it.

Would you be able to quote a specific example from Murakami and maybe it will be possible to say more about what he is getting at?

My Japanese friend had a daughter named Idumi (pronounced Idzumi) written out in Hiragana. He explained to me that there was a Kanji of that name but he and his wife had deliberately refrained from using it. There was some significance to that choice although I no longer recall what it was. Amusingly, at age a year and a half, when she heard us speaking English, she burst out in the A,B,C song so I assume they were determined she would learn English early. I think that says something about their mindset.

It is more like being named Cindy, Cindi, or Sindee. It doesn’t really tell you anything, other than perhaps if your parents were idiots. But worse in Japanese. Seeing a name doesn’t mean that you are sure how to say it and hearing a name doesn’t mean that you are sure how to write it.

I just thought of a relatively simple-sounding Japanese name off the top of my head and googled to see if it made a good example, and boy does it ever:

Murakami uses a lot of non-standard names FYI. If he can throw a reference in he will. Malta and Creta are certainly not Japanese names.

There are multiple ways to transliterate Japanese. In English speaking contexts, the Hepburn system or its many derivatives are used. This system preserves the pronunciation. Other native systems are Kunrei-shiki or Nihon-shiki which preserve a uniform spelling progression but don’t always match pronunciation. So for example, the same name might be spelled Yoshi in one but Yosi in the others. Japanese also uses a macron for long vowels, or as that’s not always easy in some typefaces, a circumflex or doubling letters. Long o is also strange, sometimes it’s ou, sometimes oo, sometimes oh (as in Shohei Ohtani), it’s a personal choice in some cases, but also most long "o"s are ou, but some are always oo. Part of this is because Japanese has a long history of ancient loans from Chinese. Kanji 大 means “big” and in Chinese form (on’yomi) it’s pronounced “dai” and in Japanese form (kun’yomi) it’s oo.

Also, Japanese went through a spelling reform circa 1949, so people who immigrated before then have the “old” spelling, like Daniel Inouye would be Inoue nowadays, the “ye” character is deprecated.

I glanced in a couple of my Murikami books for examples (searching for the word “name”). Here’s one from The Windup Bird Chronicles:

She pulled her feet up into the chair and put her chin on her knees. “How about your name?” I asked.

“May Kasahara. May… like the month of May.”

“Were you born in May?”

“Do you have to ask? Can you imagine the confusion if somebody born in June was named May?”

Here’s a longer one from 1Q84

“Aomame” was her real name. Her grandfather on her father’s side came from some little mountain town or village in Fukushima Prefecture, where there were supposedly a number of people who bore the name, written with exactly the same characters as the word for “green peas” and pronounced with the same four syllables, “Ah-oh-mah-meh.” She had never been to the place, however. Her father had cut his ties with his family before her birth, just as her mother had done with her own family, so she had never met any of her grandparents. She didn’t travel much, but on those rare occasions when she stayed in an unfamiliar city or town, she would always open the hotel’s phone book to see if there were any Aomames in the area. She had never found a single one, and whenever she tried and failed, she felt like a lonely castaway on the open sea.

Telling people her name was always a bother. As soon as the name left her lips, the other person looked puzzled or confused.

“Miss Aomame?”

“Yes. Just like ‘green peas.’ ”Employers required her to have business cards printed, which only made things worse. People would stare at the card as if she had thrust a letter at them bearing bad news. When she announced her name on the telephone, she would often hear suppressed laughter. In waiting rooms at the doctor’s or at public offices, people would look up at the sound of her name, curious to see what someone called “Green Peas” could look like.

Some people would get the name of the plant wrong and call her “Edamame” or “Soramame,” whereupon she would gently correct them: “No, I’m not soybeans or fava beans, just green peas. Pretty close, though. Aomame.” How many times in her thirty years had she heard the same remarks, the same feeble jokes about her name? My life might have been totally different if I hadn’t been born with this name. If I had had an ordinary name like Sato or Tanaka or Suzuki, I could have lived a slightly more relaxed life or looked at people with somewhat more forgiving eyes. Perhaps.

You might could chalk it up as another thing that Murikami is fixated on writing about, like food and music and women’s ears.

Along these lines, it was once semi-settled convention (c. 1920-1960?) that American Jews named their sons “Louis,” not “Lewis.” (Likewise “Stuart” vs. “Stewart.”)

After I saw the American movie (500) Days of Summer when it came out in 2009, I made a note to myself to mention one scene in the movie that I thought a couple I knew would be interested in. They have a daughter named Autumn. I usually only see them once a year. When I saw them that year, I mentioned the very last scene of that film. Right at the end a character named Autumn was introduced. Her name was a contrast with the main female character of the movie, whose name was Summer. I had never heard the name Autumn anywhere else. They said that their daughter Autumn was neither born nor conceived in Autumn. They didn’t say why they named her Autumn. Maybe it was just a nice sound to them.

I don’t like the term “spelling” when referring to the selection of characters used for particular words because it can give speakers of English the wrong impression based on our experience with English spelling.

“Spelling” in English is fundamentally different than how characters are used in Japanese.

In English, the letters themselves have no inherent meaning when used to spell words. The letters “y”, “i” and “ee” in Cindy, Cindi, or Sindee, to use the example above, have no intrinsic meanings. They are simply phonetical representations of the “i” sound in ˈsɪndi (IPA).

In contrast, all of the kanji for “Yuki” each have intrinsic meanings of their own. Picking two different kanji, 雪 means “snow” and 幸 which means “happiness”. While I used to tease one 雪 I dated that her parent assumed her to be a cold person, the meaning is closer to pure or white (represting good).

The kanji 幸 has many standard readings such as “ko”, “sachi” and “shiawa” when written 幸せ. As a girl’s name parents can simple declare that the pronunciation is “Saki”, “Tomi”, “Tomo”, “Miyuki”, “Yuki” or “Sachi” among others.

Some Japanese put a lot of time and energy into thinking about the characters and pronunciation of potential names, as well as the number of strokes in the characters, which is of importance for fortune telling for those who believe in that.

It’s possible to write a name in either hiragana or katakana which then give the name a pronunciation without an inherent meaning. Choosing not to have kanji also says something about the name.

What @TokyoBayer said.

Kanji are simplified hieroglyphs with actual meaning of their own. The letter ‘r’, in English, just represents a sound and doesn’t mean anything beyond the pronunciation.

Japanese only has something like 40 sounds (syllables), but it has 10,000 kanji. For any one sound, you have a lot of options for which “idea” to associate with it.

Since most personal names are two characters in Japanese (two syllables), you can think of it like having a collection of 10,000 paintings and you get to choose which two to put together, to say something about the person that you’re hoping to introduce into the world.

Deliberately choosing unconventional spellings for conventional pronunciations or unconventional pronunciations for traditional spellings tells you something deliberate about how someone (or their parents) is perceived in English, too. Would you think the same of a Sindee as a Cindy?

I think the issue with Japanese names in particular, is that there are so many homonyms in relation to names that in Japan it is not uncommon for people to ask what Kanji make up your name. Not necessarily because they find it unusual, but as in the example with Yuki, there are many ways to get the same sound. As @TokyoBayer mentioned, sometimes the choice of the kanji is based on the number of strokes, so a Japanese parent might like how a particular name sounds and then take the time to find the characters that have the right number of strokes and combine to make the sound they want. Another consideration is the Kanji of the parents (or grand parents) name, which they want to include it as part of their child’s name. I think that is a little better than adding the 3rd (or the 15th) to a name.

Yes, there can be significance in the Kanji chosen for a name, which is as pointed above, is not exactly its spelling. And given the variety you can have with names that sound the same, very few kanji choices are considered “unusual”

One thing that is interesting, is that regardless of the kanji a lot of online forms actually ask for your name in katakana which is typically used for foreign words, but is often use for pronunciations in a way hiragana is not. Sometimes you can change it later in the registration (or whatever) process, sometimes you can’t.

//i\\

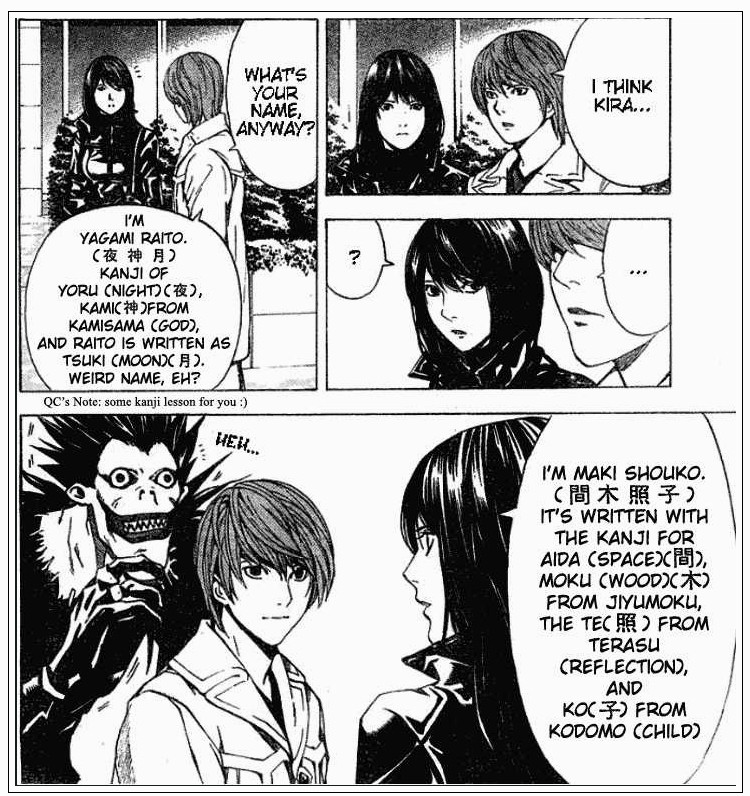

When two Japanese characters meet each other in manga, it isn’t unusual for them to have a conversation about their names’ kanji. Manga is read right to left:

Reddit:

https://www.reddit.com/r/deathnote/comments/olkiv5/why_does_light_explain_his_name_to_naomi/

That’s a manga where you’d think people would want to avoid having their proper “spellings” unknown!

Spoiler from the acclaimed manga/anime:

Indeed, Maki Shouko is lying: her real name is Naomi Misora. Ryuk the shinigami knows this which is why he is chuckling.

Coming back to this question in the OP. Yes, these is a difference between names in Japanese and in English in this aspect, and deciding on the meaning of a name is more important in Japanese culture.

Athough English names have meanings, it’s not really a big deal for most people as evidenced by these statements in the OP. Looking online, Edward

and David has the meaning of “beloved” but the meanings of names just aren’t that important.

When deciding on names for their children, it’s customary for Japanese parents to carefully choose the meaning of the name. As my friend explained it, this is one of the first things parents can provide for their children. It’s sort of like conveying a hope for the children to have particular strengths.

My friend was surprised that I chose the English name for my son just because I like the name, and without carefully considering the meaning.

Japanese tend to place more importance in auspicious natures of things, which is why the number of strokes in characters is important. Both the family name and given names are added together, which is one reason why many different possibilities are popular.

This is a good point. This is not only for unusual names but also happens with common names because of the number of homonyms.

There definiately are unusual names.

The numbers of unique names has been increasing.

Japanese friends say that they have noticed this more in the last 20 years compared to previous. I joked with one friend today because she said “recently” meaning in the last 20 years. We’re getting to the age where 20 years is recent.

Katakana is more of a block style while hiragana has more curves, so katakana can be read more easily. The use of katagana for pronunciation of kanji predates computers. Most online forms ask for both the kanji and katakana.

It’s not particularly common unless there is a special need to explain the name and it’s rare in real life for that to happen.

In Japanese society, adults typically use just their family name and family names have fewer homonyms. I had a customer Honda which had the characters 本多 instead of the more common 本田 and when we first met he did explain that.

However, most family names don’t have homonyms so it’s not usually necessary.

On a somewhat related note it is common for manga to include tiny kana pronunciation guides for names (and some other words), at least the first time they appear. (I presume that is common in other print media aimed at children/teens but less common in material for adults.)

Here is the first manga page Google Images gave me for raw manga

And a Google Lens translation of part of it

I had never heard the name Autumn anywhere else. They said that their daughter Autumn was neither born nor conceived in Autumn. They didn’t say why they named her Autumn. Maybe it was just a nice sound to them.

I have a friend named Autumn. She’s Anishinaabe, though, so that may be more a Native thing.

I minored in Japanese a zillion years ago in uni, so this may be misremembered, but it’s my understanding that when Japanese businessmen exchange cards, it’s polite to study the other guy’s intently and ask all the questions you want about proper pronunciation if the name is uncommon or the kanji are difficult. It’s an icebreaker that adheres nicely to regimented rules of decorum.

Toe-may-toe, toe-mah-toe?

Brings to mind the time (Chinese, not Japanese) when those protesting the policies of Deng Xiaoping would break bottles because the name Xiaoping sounded like “little bottle” in Chinese. (Mandarin?)

I assume from the conversation above (and the bit about peas) that commentary and jokes on the meaning of someone’s Japanese names are not uncommon?

(Side note - are there names the equivalent of “Bill Smith” or “Bob Jones” that are so common as to be almost cliche? Or is it more along the lines of excessive creativity like “Cyndee” or “Aliesha”?)