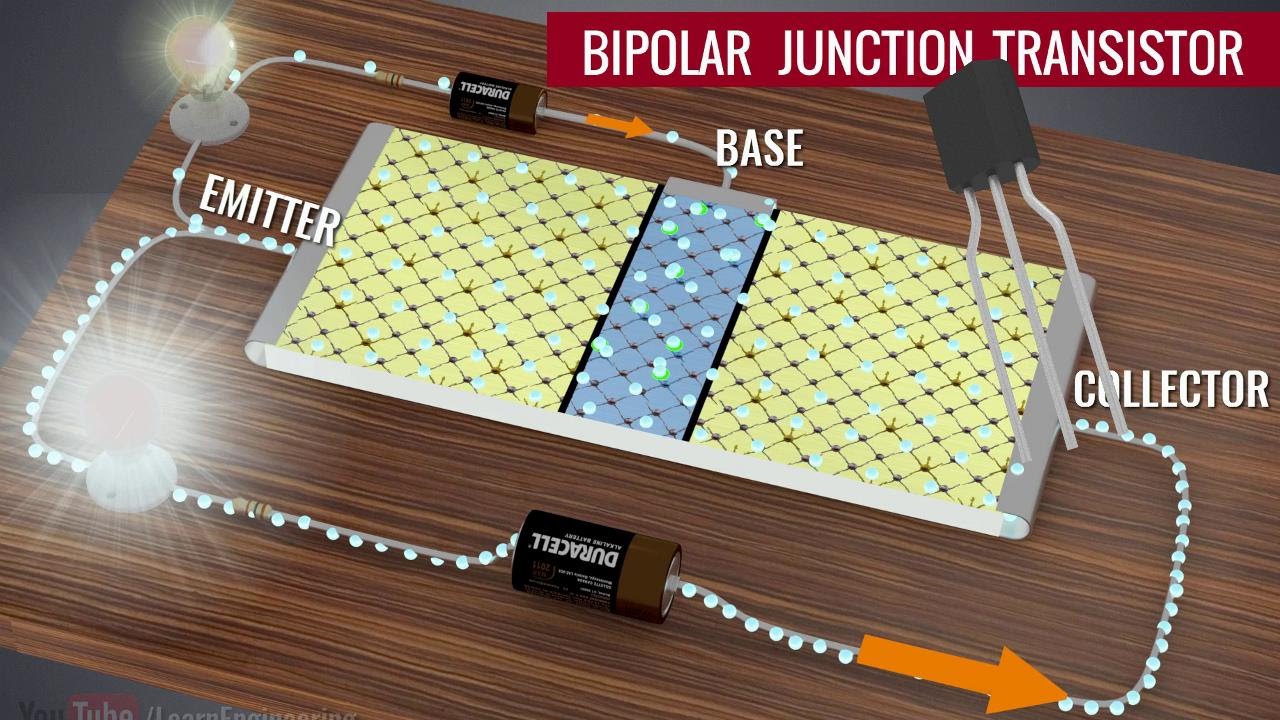

That is what several EE professors told me. That description is common in many textbooks plus the 1st paragraph of the cited Wikipedia article: “The basic function of a BJT is to amplify current”. In fact the common figure of merit Beta means collector current divided by base current, which is the BJT’s gain.

So I don’t understand the statement that a BJT transistor (the OP question) is a voltage-controlled device. The OP was asking specifically about BJT transistors, not FETs.

Re Ebers-Moll, this was a question about a high school class. At the high school level I’d recommend not getting bogged down in gate physics, academic white papers, electronic vs hole flow, etc. It would likely be more practical to illustrate and discuss real-world examples which show transistor operational characteristics and behavior.

E.g, why do modern CPUs get so hot when switching speed increases? A main reason is they’re spending more time in the active region, not saturation or cutoff. This could be illustrated with a transistor characteristic curve: https://www.electronics-tutorials.ws/transistor/tran37.gif

A modern CPU uses FETs not BJTs, but the same principle applies: in cutoff no current flows, so there’s little power dissipation. In saturation the transistor approximates a conductor having little resistance, so likewise little power dissipation. As it switches ever faster, it spends more time in the transition or ohmic range where it is dissipating power.

This also explains why a high-power semiconductor linear amplifier is difficult (and expensive) to construct even today. By contrast a high-power semiconductor relay can handle very high power because it’s either on or off.

CPUs which contain billions of transistors do not tolerate heat well, as seen by the constant focus of computer hobbyists on “never exceed” CPU temperatures, which are quite low.

By comparison a vacuum-tube linear amplifier can handle tremendous power, partially because it can tolerate heat. This photo shows two of 20 final amplifier tubes from WLW which before WWII handled 100,000 peak watts per tube, or two megawatts peak envelope power total. The base is a water cooling jacket which was piped to a cooling pond.

Today high power solid state broadcast linear amplifiers still cannot manage high power per device so they digitally split the signal across 60 or so RF modules then combine the output. To equal the WWII-era WLW output would require about 600 solid-state transmitter modules.