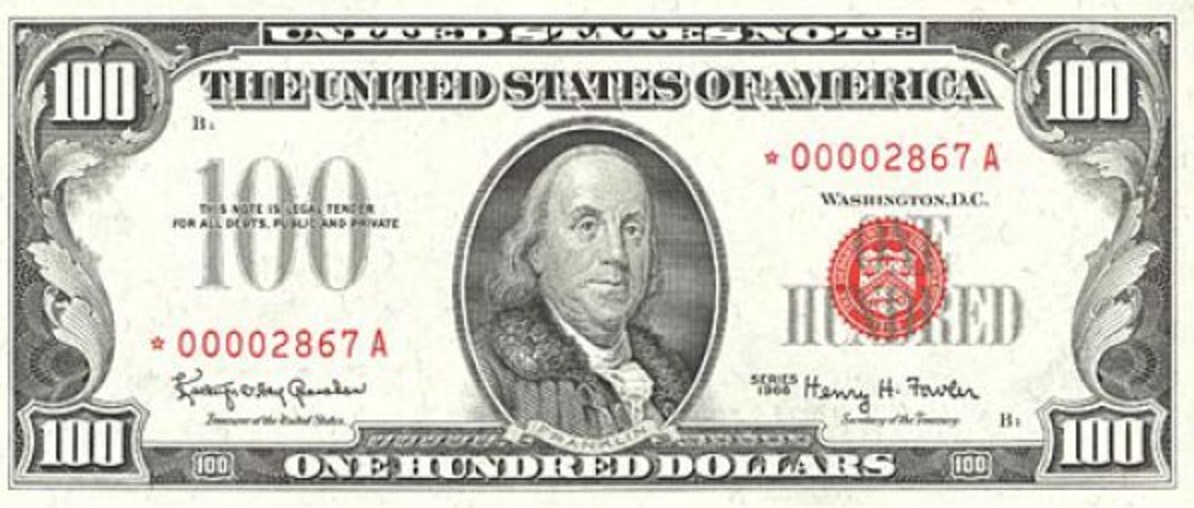

Are any SDMB posters notaphilists? A United States Note is a particular type of United States currency. Unlike Federal Reserve Notes, which are an obligation of the Federal Reserve banks, United States Notes are a direct obligation of the United States Treasury. Modern United States Notes are easily distinguished from the much more common Federal Reserve Notes by their red treasury seals and serial numbers. Until 1994, the United States Treasury was required by law to keep, I believe, $300,000,000 in United States Notes in circulation. In 1966, the United States Treasury began issuing United Notes in the denomination of $100 to more efficiently meet this requirement. It met this requirement by moving stacks of unissued United States Notes from one room to another room and declaring them to be de jure in circulation. Subsequent to 1994, all United States Notes in the possession of the treasury were destroyed. However a substantial amount are still in the hands of the public and remain legal tender. Some Series 1966 and Series 1966A $100 United States Notes did end up in the hands of the public, i.e., in de facto circulation. My question for the SDMB is: By what mechanism did the Series 1966 and 1966A $100 United States Notes enter de facto circulation in the hands of the public?

I’m not sure I understand the question. United States Notes were and are legal currency and in circulation, although rare. Why shouldn’t the 1966 notes be in the hands of the public?

You are wrong, however, that the U.S. was required to keep $300,000,000 in circulation. That was a maximum.

I couldn’t find anything related to moving them from room to room. Can you cite some authority for why in the world they would do that?

Exapno Mapcase: You are correct that the $300,000,000 figure is the maximum. It was a number I quickly pulled out of my faulty memory so I could enter my long post before my battery died. However, I do seem to rememb er a number somewhere in that neighborhood. The requirement came from section 3 of “an Act fixing the amount of United States Notes, providing for redistribution of the national bank currency and for other purposes” of 1874. Section 3 of that act required that the treasury be prepared to redeem with United States Notes any now obsolete National Bank Notes presented in increments of one thousand dollars to the treasury. Section 3 of that act was repealed by section 602 (f)4 of the “Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act” of 1994. I doubt if few, if any, National Bank Notes were redeemed after 1966.

I don’t know any reason the public couldn’t hold the series 1966 and 1966A notes. I’m just wondering how the heck they got a hold of them in the first place.

As for moving the notes from room to room, that is because the Bureau of Engraving and Printing printed more notes than the treasury needed to issue. I didn’t find a cite for this today, but I do remember reading about it several times in the mid 1990’s, probably in the Numismatic News and/or the Bank Note Reporter. Maybe I can find a cite when I get home next week and have access to a real computer.

Does anybody know the amount of outstanding National Bank Notes in 1994? It is probably somewhere in the treasury’s statement of the national debt for 1994. Probably as a footnote to the last category of other miscellaneous crap that is technically part if the national debt.

Here’s a report on the Public Debt for January31, 1994:

ftp://ftp.publicdebt.treas.gov/opd/opdm011994.pdf

(Change the ‘011994’ to ‘021994’ for February and so on.)

Non-interest bearing debt is near the very end of the document; five categories of banknotes are included. All figures in $Millions

275 - United States Notes

66 - National and Fed Res Banknotes assumed by U.S. on deposit of lawful money for their retirement

2 - Old Demand Notes and Fractional Currency

4 - Old Series Currency (Act of June 30, 1961)

192 - Silver Certificates (Act of June 24, 1967)

The footnotes show that this debt is not subject to the statutory limit; and that 25+0+31+89+200 (for the five categories of notes) are determined to have been destroyed or irretrievably lost and therefore excluded.

Is this Wiki wording correct? It indicates they were printed through 1969 and issued through 1971:

“1966: The first and only small-sized $100 United States Note was issued with a red seal and serial numbers. It was the first of all United States currency to use the new U.S. treasury seal with wording in English instead of Latin. Like the Series 1963 $2 and $5 United States Notes, it lacked WILL PAY TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND on the obverse and featured the motto IN GOD WE TRUST on the reverse. The $100 United States Note was issued due to legislation that specified a certain dollar amount of United States Notes that were to remain in circulation. Because the $2 and $5 United States Notes were soon to be discontinued, the dollar amount of United States Notes would drop, thus warranting the issuing of this note. $100 United States Notes were last printed in 1969 and last issued in 1971.”

Dennis

Unlike U S. coins for which the date is the actual date issued, for U.S. currency the series date is the date a particular design was first printed and the same series date is used until there is a design change. Thus the series 1966 notes could have been printed in years after 1966. In 1969, David Kennedy became Secretary of the Treasury resulting in a minor design change and the printing of the series 1966A notes. (Sometimes a minor design change results in the addition of a letter suffix instead of a different year.) Thus the series 1966A notes could have also been printed in any year after 1969.

Perhaps an additional question for this discussion might be: Exactly what does it mean when the treasury says that a note is “issued”?

What is the purpose of United States notes?

The origin of United States Notes was during the Civil War with the issue of a strictly fiat currency known as legal tender notes or greenbacks to finance the war.

After the Riegle Act of 1994, the United States Notes no longer serve any purpose and are retired (destroyed) whenever they are returned to the treasury.

I’ll bet that those notes are worth more than face value in the numismatics market, so you’d be foolish to return one to the Treasury.

They go for ~$150 on eBay.

Note that $100 in 1966 is the equivalent of about $800 today. So stashing away one of those back then represents a very poor ROI.

If you have one, sell it. It’s not going to get more valuable in real terms.

An absolutely flawless perfect uncirculated one might go for up to almost a thousand dollars. It’s all about condition.

And I’ll bet you’d have a lot more if you bought an S&P 500 index fund or invested in Berkshire Hathaway back then. But that wasn’t the point. It was simply that few of these notes are going to be sent back to the Treasury.

From Septimus’s link and a similar report for January of 1966, I see that the amount of public debt in the form of “National and Federal Reserve bank notes assumed by the United States on deposit of lawful money for their retirement” was reduced by approximately 22 million dollars from 1966 to 1994. (IMPORTANT: A Federal Reserve Bank Note is not the same thing as a Federal Reserve Note!). The 1874 act that I mentioned in an earlier post requires that National Bank Notes be redeemed in United States Notes. Could this be the reason that some of the Series 1966 and Series 1966A One Hundred Dollar United States Notes left the possession of the treasury? If so, exactly how did this work? I would guess that there were some banks involved, including Federal Reserve banks.

I guess that my prior assumption that “few, if any, National Bank Notes were redeemed after 1966” made in an earlier post was wrong.

And I’ll bet you’d have a lot more if you bought an S&P 500 index fund or invested in Berkshire Hathaway back then. But that wasn’t the point. It was simply that few of these notes are going to be sent back to the Treasury.

Did S&P 500 index funds exist in 1966? This article says they weren’t invented until 1976.

Again, not really the point.

The origin of United States Notes was during the Civil War with the issue of a strictly fiat currency known as legal tender notes or greenbacks to finance the war.

But why were they still being issued a century after the war, and bake a century after the Fed was set up?

The Fed was only set up in 1913, and US Notes were last issued in the 1970s as mentioned above. The only reason they were kept around is because they allowed the Treasury to engage in a small bit of monetary policy by issuing US Notes to buy stuff for the federal government (thus increasing currency circulation a bit), and they kept up to $300 million of them in reserve for that purpose. This was widely recognized as obsolete fairly early into their history, but few people were interested in amending the statute to get rid of them. Eliminating the gold standard in 1971 removed any last justification for their presence since the Fed was now solely responsible for monetary policy and maintaining the value of the currency, and no more US Notes were printed after 1971. The Treasury was still required to keep them “in circulation” until 1994, but AFAIK they mostly just sat in vaults at the Treasury. All the notes in the Treasury’s possession were destroyed by 1996.