I frequently hear primitive human brain functions referred to as our “lizard brain.” I’m not sure who used said this, but is this is just baseless hyperbole? How far back do you have to go before lizards and homo sapiens have a common ancestor?

Mammal brains are a lot more complicated than reptile brains. All of the basic parts in a reptile brain are still present in a mammal brain, but we also have a lot of parts that reptiles don’t have. So the term “lizard brain” is sometimes used to refer to the parts of the brain we have in common with them, which do indeed have fairly basic functions (more or less the same functions in them as in us).

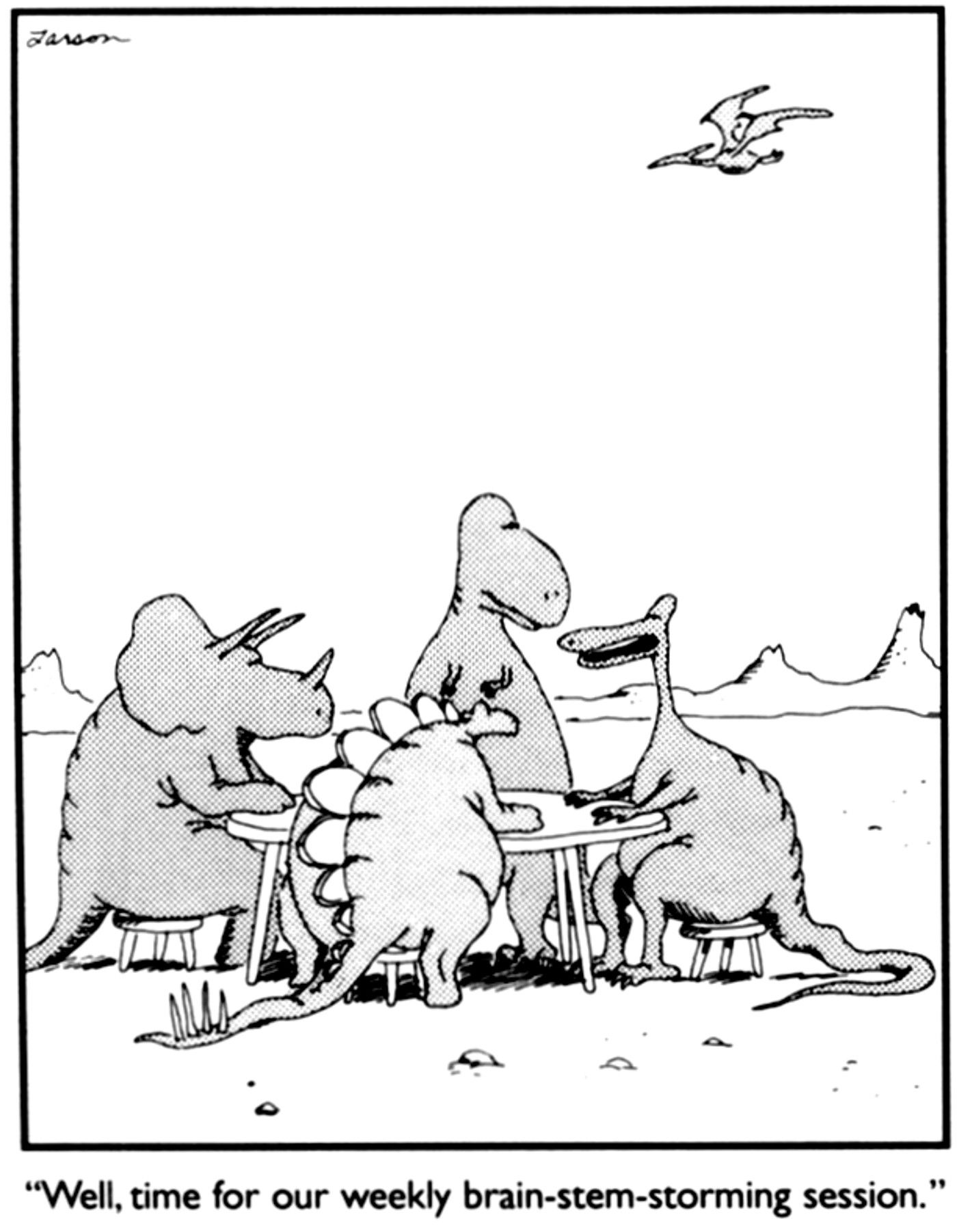

Here’s a really good visual of how it all developed and compares. If the figure continued on to humans, then it would include the frontal cortex, which is a section added on at the top as that figure is oriented.

The “reptilian brain” is properly referred to as the “Limbic system” and although we often override it in normal life, it can completely take over during times of extreme threat. That is why the actions of victims sometimes don’t feel logical or normal to us. When we say “instinct took over” we are talking about the limbic system.

Reptiles and humans actually share a brain system that we both inherited from fish, so your “common ancestor” question is currently impossible to answer.

Humans and reptiles belong to different classes within Amniota - we were certainly distinct lineages by the start of the Permian, about 300 million years ago. Part of the confusion is that lizard is used as a sloppy synonym for a land-dwelling reptile that’s not a dinosaur when, in fact, it is a branch within the reptile line [sauropsids]. We are proudly synapsid.

Not really. The notion comes from the conceptual model of the triune brain, credited to neuroscientist Paul MacLean but it is actually been subjected to a lot of interpretations. The idea is that the basal ganglia in mammalian brains is derived from structures first developed in reptile brains (the “reptilian complex”, often referenced as the “R-complex” in neuroscience literature) and is essentially unchanged in mammalian brains onto which the paleomammalian complex (also collectively referred to as the “limbic system”) and the neocortex are developed. The general theory is that the R-complex provides basic instinctual behavior such as eating and voluntary movement, the limbic system developed to allow emotions and simple learned behavior, and then the neocortex found in “higher” mammals where complexity of voluntary behavior is qualitatively correlated to the gyri and sulci (convolutions) in the tissues of the neocortex. It has been used to justify why only said ‘higher’ primates are capable of emotions, learned behavior, and (in primates) some form of abstract communication.

However, it should be evident to anyone who has read more up-to-date literature on animal behavior or affective neuroscience that this simplistic view of cognitive function and mapping to brain structures is at best misleading and largely untrue. Aves (birds), which are distinct in their evolutionary lineage from mammals, lack any structures that are identified as the limbic system or mammalian neocortex (although more recently homologous structures have been discovered in the brains of some bird species), but the majority of animal behaviorists agree that many birds species have identifiable affect (emotions), learned behavior, and even some approximation of language or at least neural structures that allow them to accurately mimic language to a degree that is not satisfactorily explained as ‘instinct’.

Most neuroscientists today regard the “limbic system” as an archaic and inaccurate model of affective behavior even though the term still permeates in the field of psychology. It is clear that many ‘lower’ animals are capable of complex emotional behaviors even though they (probably) lack cognitive capacity for executive functions involving planning or emotional restraint, and even then, many animals exhibit behaviors that are far more complex than can be dismissed as just instinct alone. In fact, there is really no accepted definition of what “instinct” even means or how we could experimentally distinguish between instinct and conscious decision-making.

If you are really interested in this topic I highly recommend reading The Archeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotions by renowned affective neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp and psychotherapist Lucy Biven. It is a dense book any at 500 pages before references is not short, but Panksepp and Biven lay out all of what is commonly understood (and correct many misunderstandings) about the evolutionary development of emotion, “instinct”, and learned behaviors including neural correlates to defined emotional states. It is really a beautiful book and worth multiple read-throughs if you are really interested in the topic of affective neuroscience.

In fact, technically speaking we are all “fish” (in a casual sense) as members of the vertebrate lineage, but of course phylogenetically we fall into distinct clades based upon (mostly) evolutionary trajectories.

Stranger

Thank you for this phrase. It describes so many weird little linguistic loopholes.

Funny you use baseless but I usually understand it (edit: lizard brain) to mean basic instincts.

I was going to say much of what @Stranger_On_A_Train said. But less eloquently, and without the recommended book. The model is commonly trotted out, and has some conceptual use (I think I first came across it in an old Carl Sagan book?), but is a gross simplification that has been largely discredited.

Stranger

That’s it. Read it many decades ago. Ontogeny may recapitulate phylogeny, but that’s a little like saying your smartphone is the same as ENIAC because they both have screens and wires. Still, something has to explain goblin mode.

Just so.

“Convergent evolution of complex brains and high intelligence”

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rstb.2015.0049

The phrase is a remnant of the March of Evolution construct, an arrow of progress leading to us.

But intelligence, defined as

has evolved in a variety of brain structures and evolutionary lines.