That’s a great point. I would never use the word “prodigy” to describe my children. They are gifted, but not in a one-in-a-million way like true prodigies.

I am practically the dictionary definition of a prodigy, by which I mean the encyclopedic definition, by which I mean that World Book Encyclopedia published a “Year in Medicine” volume in the 1980s illustrated with a photograph of me.

It ain’t true. I was just a tiny little moppet with a violin and no stage fright, but prodigy was not the right descriptor.

Nevertheless, I read that article some years back, and it defined a prodigy as someone who performed, as a child, at an adult level on a skill that was valued in their culture. I’m finding a similar definition here:

As you can see, that definition is extremely limiting, meaning that there are a lot less prodigies out there than there are parents who think they have prodigies. Your kid who was reading at the age of six months ain’t a prodigy, unless at the age of eight they’re writing a novel analysis of the Crimean war, or at the age of nine they’re translating the Odyssey from the ancient Greek. Your kid who learns algebra quickly: have they proposed a formula for solving trinary quadratic equations yet? How are their peer-reviewed articles coming along?

I think I have known one child prodigy in my life, by that definition. I grew up knowing Lenny Ng (Google him if you want), was in math competitions with him, was jealous of and humbled by him. True prodigies are far beyond what we think of in “proud parent” terms.

What is your experience on how linearly social aptitude tracks for gifted children?

I can speak anecdotally, researched-based (and recalled from my reading on the subject a decade ago), and speculatively.

Anecdotally, both from whole-classroom teaching and as a gifted education specialist, I see a very wide range of social aptitude. I have kids in my class who are breathtakingly kind and whom everyone, teacher and child alike, loves. I have kids in my room who are clearly going through something and are handling it with vicious cruelty. I have kids in my room whose social skills are best described as “oh, bless your heart.”

Research-based, the stereotype of the socially-stunted genius doesn’t hold up. From what I remember, studies of the social aptitude of gifted kids finds that they are, on average, slightly above kids in general, sometimes coming across as more mature emotionally than their peers.

Speculatively? I think there are a few factors that go into the range:

- I see a higher than average number of kids with autism or related conditions. This can result in specific brilliance coupled with massively inflexible behavioral ideals. When a kid accidentally writes his algebraic response to question 8 in the space for question 9 and starts screaming and hitting himself in the head, it makes him a lot less popular with his peers.

- I also see a lot of kids who are highly advantaged by their parents’ wealth, education, and stability, and such parents may be likelier to emphasize the sort of middle-class social behavior that I tend to favor.

- Kids who are cognitively advanced may apply those cognitive skills to figuring out social situations. I remember a brilliant kid I taught who was also brilliant at socially tormenting and bullying his peers. He could tell a joke that would have the whole class laughing at some poor kid; it would be a clever turn of words that would twist the knife. And then other kids use their cognitive skills to empathize with other kids, to reason about what other kids need, and to show love and generosity.

I think it’s complicated, and I don’t have a simple answer.

The reason I ask is that I suspect the trepidation against skipping grades was based on the social challenge of that (of course being gifted around age matched kids not gifted is a challenge as well).

I read this:

And wondered if the scores of Section IX were predictive of later social function in that older child environment. FWIW I see gifted kids as a very diverse group. There are those with very narrow gifted skills and those gifted more evenly. The latter to my take will usually do well socially even in challenging circumstances.

On definitions: context matters, a little. If the OP had asked “Have you ever met a real prodigy?” yeah, I would not have answered talking about my kid. I did figure that if the OP was directed to parents/relatives of “prodigies,” on a message board that isn’t, well, Reddit-sized, that what was meant was something where the OP might actually get a couple of responses.

I would definitely not say my kid is one in ten million, but I would be pretty comfortable saying that my kid is at least one in a hundred thousand (more if you restrict it to girls). My other kid is gifted, but not like this; I would not call him a prodigy even by the standard of one in a hundred thousand. Mind you, he likes thinking about intellectual subjects a lot, and doesn’t have her twice-exceptionalities, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he got farther in the end because of that.

<full “one-up” mode>

that’s nothing, our youngest was already going to the potty at this age (and I was really greatful, as diapers cost a lot of money and at this time I was out of work)

![]()

Well, if kids don’t behave well, their parents can give them away to others, hence “gifted kid” … any other questions?

add on Q, (quite on topic)

Those of you that witnessed “highly gifted” kids some time ago … how did they turn out in life as an adult? … were they highly successful, successful or just doing OK? … iow: did it translate?

By “prodigy”, I would classify someone who is, say, in the top 1% or 2% of their peers in some category. Is that a sufficient definition?

As far as adults go, from what I’ve seen, it’s just as widely variable as people who are not gifted in some way. For example, the smartest kid at my junior high wanted to be a truck driver and got razzed a lot for it, and was valedictorian at the voc/tech school. He later got an associate’s degree in diesel mechanics, and taught that subject at the same school for many years. (I’m pretty sure he’s retired now.) He would have been an absolute failure as, say, a doctor or a lawyer, and I have no doubt that people who studied with him, when employers saw their applications, would know they were capable of doing the job without extensive interviewing.

I also recently read about a 16-year-old college student who died in a tragic accident many years ago, and without going into further details that could identify them, wondered if this young person would have, for instance, had a nervous breakdown a couple years later and worked for a while at the local grocery store before furthering their education at long last. I saw a few examples of that myself.

I think that is very “lenient” … according to your definition, in a group of 50 kids (aprox. 2 school-classes) you’d find one prodigy…

that’s more gifted/good talent-territory to me …

In the 65 third graders at my school, 22 of them scored in the top 1 or 2% on a nationally-normed test in at least one of three subcategories. There are other kids in that cohort who are not top 1 or 2% on that test, but surely are top 1 or 2% in dance, or violin-playing, or football, or Minecraft, or gymnastics.

That definition, I fear, makes the term unworkable.

You just described a longtime friend of mine. Never seeming gifted, he got fed up with his school in Grade 11 and quit, headed for the Canadian Forces. If there was a Forces course with a practical application, he took it. When he came out of the Forces, ten or twelve years later, he was a qualified diesel/gasoline mechanic, a scuba diver, and a truck driver (complete with instructors’ qualifications and road-testing qualifications). Martial arts was a hobby, and he sharpened his skills in the Forces, and ended up teaching hand-to-hand combat skills. And, oddly, though he was not a cook, he learned how to cook. “I watched the cooks in the mess hall kitchen, asked them questions, and learned from them.” And to this day, he can whomp up something tasty out of seemingly nothing.

I once said to him that with all his mechanical experience, he would have no problem getting into an engineering school at a university, but he said that he didn’t want to. “I don’t want to be in a lecture hall; I want to be in a shop, working on stuff.”

He taught me to drive a semi-rig. As far as I know, I’m the only graduate of my law school who ever has. He’s kind of proud of that.

The really weird part is that a guy like him and a guy like me could become best friends. But we did.

By whatever metric Illinois public schools used in the 1970s, I was determined to be reading at a 9th grade reading level in 3rd grade. Yes, I was given the “gifted” label. Anyway, I remember this exercise we did in the library: the librarian was going to teach us how to look up words in the dictionary (remember, this was the 70s, so a big ol’ book kept on a podium somewhere in the library. Anyway, she gave us third graders books intended for fifth graders, and told us to write down five words we didn’t know. When I couldn’t find five words I didn’t know, the librarian said I was lying and just didn’t want to do the exercise. I was pissed, as you can tell by the fact that I’m still salty about it 45 years later.

Anyway, my parents realized I was ahead of the curve reading wise when I was maybe two-ish, and we went to Dawson’s Furniture and I knew where we were because I recognized the name on the sign.

Now this is a really interesting question (though interesting enough it might want to be a spinoff thread).

I knew a fair number of highly-gifted kids as an adolescent (and I’d say I was one myself, though I don’t consider myself a prodigy). There were a few that stood out even in that group – again, I don’t necessarily want to call them prodigies, but let’s say that they were exceptional even in groups that were already selected for high giftedness. I think basically all of those went on to lead quite full and interesting lives – I think they are highly successful in that they are doing really interesting things, not all of which individually may have been successful – in a range of disciplines, ranging from tech to academics to nonprofits to politics. As a larger group, the “highly-gifted” kids tended to turn out successful (occasionally highly successful) in a range of disciplines, where I define “successful” as “happy with their lives, reasonable career, often making a difference in a small way, but not necessarily changing the world.” That’s the vast majority (including me). I do know a few who are just doing OK (where I define that as “having a fair amount of struggle in some way”); for the people I know this is usually due to factors outside their control, like poor health or family health issues. (In one case, however, the person in question believes that their personal health issues may have arisen from the kinds of stress they were put under to highly achieve due to their giftedness. So there’s that.)

I think the ones who ended up highly successful tended to not just be super “smart” or “gifted” (although that helps!) but also have a lot of drive, resilience, and curiosity, and, to be honest, less in the way of undiagnosed twice-exceptionalities. (A bunch of us found out as adults, sometimes after having our own kids, that we may in fact have been twice-exceptional, which in retrospect explains a lot.)

I spent last week at a conference for educators of “gifted” children, and had some really interesting conversations.

One of my favorite conversations was around the word itself. Over drinks after hours, I mentioned that I hated the word “gifted.” I expected either condescending pushback or a polite subject-change, both being reactions I’ve gotten before. Instead, someone scowled and said, “Yeah, everyone hates that word, but there’s not a great alternative.”

We talked about some different alternatives, from the clunky to the jokey: “academically/intellectually focused,” “advanced,” “neurospicy,” “nerdy.” One person in the conversation, a therapist who specializes in neurodivergent clients, told me about the term “neurocomplex,” which is gaining use in some quarters.

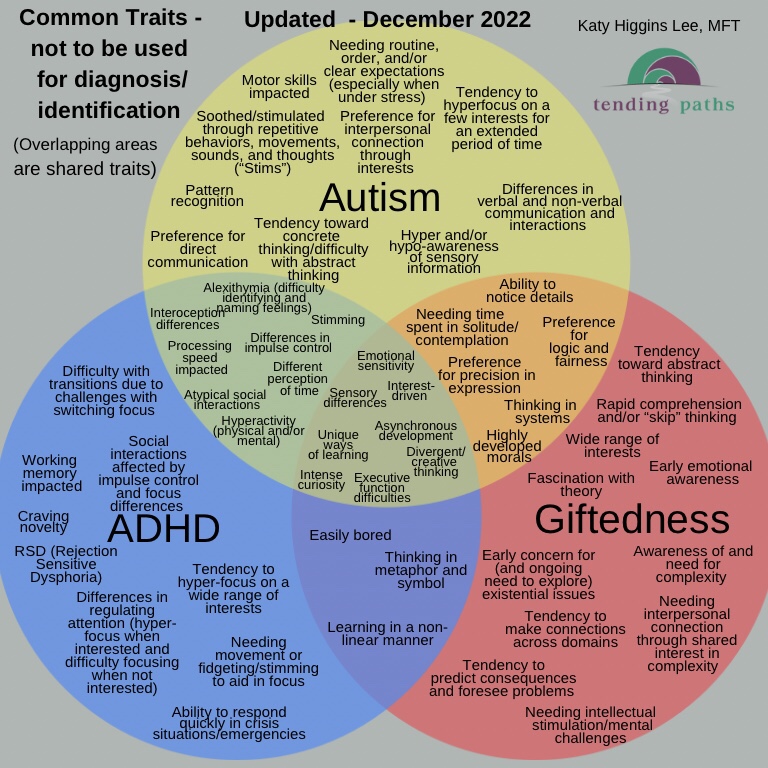

And he showed me this Venn Diagram, which I love:

I pointed out to him that of the three interlocking conditions, two of them – ADHD and ASD – literally have “disorder” in their name, while the third one sounds like a sacred blessing. He burst into despairing laughter, and responded that often the traits unique to “giftedness” can lead to struggle.

The psychologist who coined the term “neurocomplex” believes (if I understand correctly) that autism, ADHD, and giftedness overlap so much that they’re essentially a single condition at their core. When a person with this condition is well-supported, the condition manifests as giftedness. When their needs aren’t being met, it manifests as a disorder.

I don’t know if I’m 100% behind that, but I think that at least in certain cases, it’s accurate.

Fascinating! Perhaps another candidate for the “Giftedness/ADHD, but not Autism” segment might be “understands sarcasm” (or “gets jokes”)?

Agreed: that might fall under “thinking in metaphor and symbol”, but it is a little more specific than that. An appreciation for and adroitness with non-literal language use seems common with both conditions.

My brother found out after having kids, one of whom is diagnosed on the autism spectrum (not the one I mentioned in the OP) that he is 2E (twice exceptional) - intellectually gifted, with a learning disability, and he also has a sensory processing disorder that was not even suspected until this daughter was diagnosed with it. (So, does that make him actually 3E?)

I can’t help but picture a kid on a swing: “THREE E E E!!!”

Ah, that’s fascinating! I’ve believed for a long time that there’s a fuzzy line between “giftedness” and (some kinds of) ASD (*), at least (I have less personal experience with ADHD, but I certainly know a fair number of people in those Venn overlaps as well). I really get the impression sometimes that my kid has a finite amount of brain space and the vast majority of it got dedicated to logical reasoning and thinking, meaning there was less leftover for social reasoning and thinking. (And sometimes the two are in conflict; being very careful not to generalize unless logically airtight means that you are not great at generalizing e.g. people’s behaviors!)

(*) Though I also have believed for a long time that there must be multiple pathways to ASD. In my kid it seems like a natural outgrowth of having phenomenal logical reasoning skills and she fits right in that Venn diagram. Other kids on the spectrum we know don’t necessarily seem to have those compensatory abilities.

I also really hate the word “gifted” ![]() I prefer “highly asynchronous,” which is really what my kid is – significantly above neurotypical peers in math, significantly below in socioemotional, pretty much bang on in language arts (though if you break it down more, she’s also asynchronous there – she can read and grasp factual books above grade level, and her vocabulary is very good, but understanding gestalt and nuance are below grade level). She also hit all her physical milestones pretty much bang on or a little delayed (except for losing her baby teeth, which she did much faster than her peers, go figure).

I prefer “highly asynchronous,” which is really what my kid is – significantly above neurotypical peers in math, significantly below in socioemotional, pretty much bang on in language arts (though if you break it down more, she’s also asynchronous there – she can read and grasp factual books above grade level, and her vocabulary is very good, but understanding gestalt and nuance are below grade level). She also hit all her physical milestones pretty much bang on or a little delayed (except for losing her baby teeth, which she did much faster than her peers, go figure).