Many have taken issue with your columnist’s contention that Trump’s election could be blamed on neoliberalism and offered their own explanations. Clearly a followup column is called for. Short version: Economic insecurity is why Trump beat Clinton in the electoral college. Cultural insecurity, to which I gave insufficient attention in my OP, is why he got 63 million votes.

Before we get into that, a sampling of competing views:

thorny_locust then cites a Guardian story entitled “White and wealthy voters gave victory to Donald Trump, exit polls show.”

Let’s take this step by step.

First, to acknowledge the obvious: Trump had a much better grasp of the mood of the electorate than Hillary Clinton did. Not saying that was their only difference, but it was pivotal. More on that later.

Second, Trump reflected a worldwide populist trend. A research group that maintains a database of these things says global populism is near a 30-year high. Populist leaders and movements can be found at both ends of the political spectrum, but the ones that have gotten the most attention are on the right - Bolsanaro in Brazil, Orban in Hungary, Duterte in the Philippines, Modi in India, the Brexit movement in the UK, and many more. The fact that Trump was part of a global phenomenon strongly argues against a strictly U.S.-centric explanation of how he wound up as president.

Academics commonly attribute the worldwide rise of populism to globalization, but they disagree on exactly how the latter gave rise to the former. Researchers tend to fall into two camps - one emphasizing economic insecurity (offshoring of jobs threatens workers’ livelihoods), the other cultural insecurity (outsiders threaten the country’s traditional - in the U.S., white Christian - way of life).

A good case can be made either way, and you need to look at the question from both angles to get a complete picture. Political scientist Yotam Margalit draws a useful distinction between outcome significance and explanatory significance. Outcome significance is (often) a relatively small change that produces outsized results. Margalit concedes that, in 2016, economic insecurity had major outcome significance, in that it enabled Trump to win three key states - Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin - and thus the election. He cites a study demonstrating as much.

But he goes on to say economic insecurity has only modest explanatory significance - it doesn’t really tell you why 63 million people voted for Trump despite his manifest shortcomings. Margalit believes cultural insecurity offers a better explanation for this astonishing fact. I acknowledge the truth of this, and here attempt to provide a more nuanced account.

With Margalit’s approach as a lens, let’s consider the competing explanations for Trump’s victory:

Voters were rejecting the neoliberal policies advocated by the leaders of both political parties. This is the critique from the left, as described in the OP. Even if you don’t buy this argument in its entirety, elements of it deserve to be taken seriously - in particular, the claim that the neoliberal emphasis on free trade laid the groundwork for a massive offshoring of U.S. manufacturing jobs, which in turn led to a political backlash in Rust Belt states.

Scoffers may say: that’s giving neoliberalism too much credit. Globalization was inevitable - globalization here understood to mean outsourcing of manufacturing to foreign firms, with a corresponding loss of U.S. factory employment. It was made possible by the growing productive capacity and lower costs of developing countries coupled with transportation improvements such as containerized freight. It would have happened regardless.

A reasonable response to this would be: Sure, it would have happened eventually. It didn’t need to happen so abruptly. The fact that it did can be at least partly blamed on what now seems a naive faith in the virtues of free trade, a tenet of neoliberalism.

Free trade had long been advocated by Republicans. During the Clinton administration it was embraced by Democrats as well. An early step was ratification of the North American Free Trade Act in 1993. But the most dramatic changes occurred following the admission of China to the World Trade Organization in 2001, a U.S.-led move that resulted in a substantial reduction in trade barriers. The chart below, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, shows what happened next:

In the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. manufacturing employment had been relatively stable, but during the 2000s it fell off a cliff. Roughly 5 million American manufacturing jobs - one-third of the total - were lost in just 10 years.

This trend was mirrored in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. In February 2020, prior to the pandemic, these states had a million fewer factory jobs than in 2000.

In the study cited by Margalit, the economic dislocations caused by the China shock led to a shift in votes that resulted in Hilary Clinton’s loss of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, which Obama had won in 2012. From the standpoint of outcome significance, then, economic insecurity stemming from globalization is why Trump won.

If China had been kept out of the WTO, could the China shock have been prevented, or at least slowed down enough to reduce it to a China bump? There’s no way to know. What we do know is that the Obama administration was reasonably successful in getting things turned around during the depths of the Great Recession, when U.S. manufacturing jobs reached their low point. Over the next few years it launched various initiatives to rebuild manufacturing, invest in new technology, bring jobs back, and so on. Arguably these efforts had some impact, both on the economy and how people felt about it. Manufacturing jobs ticked up modestly. Obama won re-election by 5 million votes in 2012.

So if the job situation improved after 2010, why did Clinton lose in 2016? Here we turn to what Margalit believes is the factor of explanatory significance - cultural insecurity, which I acknowledge is needed to fully understand what happened. To see how this played out, it’s instructive to look at some of the other reasons suggested for Trump’s victory.

The majority of white people voted for Trump. The argument here is that whites had more money than the rest of the electorate and wanted to keep it that way. A related claim is that Trump was elected by racists, presumably white.

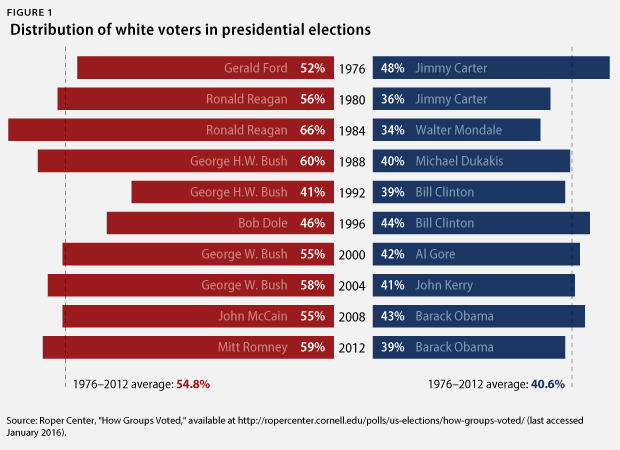

Let’s posit that Trump received 58% of the white vote in 2016. (Pew Research came up with a different, lower number in a later analysis, but we’ll skip that for now.) What this overlooks is that Republicans have gotten the majority of white votes (or plurality, in elections with three candidates) in every presidential election since 1976, when exit polls began categorizing respondents by race. Here’s a chart by the Center for American Progress:

From this we can conclude that most white people will vote for the Republican candidate no matter who it is. That doesn’t tell us anything about why they voted for Donald Trump specifically. In short, this hypothesis lacks explanatory significance.

What about the argument that Trump was elected by racists? Many of those who voted for him surely were. We lack detailed data on how whites voted before 1976, but the “solid South” reliably voted Democratic prior to the civil rights era. After Democrat Lyndon Johnson muscled civil rights legislation through Congress, southern states began voting Republican. From this one may reasonably conclude that a significant percentage of Republicans are racist, and it follows that many Trump voters were racist. But by the same logic, many of the voters for any Republican candidate are racist - that’s not something specific to Trump. So the racist argument also lacks explanatory significance.

Does racism have outcome significance? Let’s look at the vote totals in the decisive states, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Here are some graphics from a Washington Post analysis of the results from 2012 through 2020:

These states voted for Obama by wide margins in 2012, went narrowly for Trump in 2016, then swung back into the Democratic column in 2020. It’s implausible to suggest the electorates in these states were temporarily seized by racism in 2016 and then got over it in 2020. We need to look elsewhere for an explanation.

Trumpism is characterized by hatred and fear of The Other, be it other races, gays, Muslims, immigrants, or what have you. This gets close to the truth. It’s essentially the cultural insecurity argument advocated by Margalit, and is surely of explanatory significance not only for Trumpism but for populism around the world.

Briefly put, Trump voters tended to be less educated and lived in smaller cities and towns. They felt looked down on by the educated elites who lived in big cities and voted for Democrats. In common with the followers of populist leaders elsewhere in the world, they believed their country was slipping away, feared immigrants, and were susceptible to demagogic appeals.

The evidence here is abundant and well understood:

-

Nate Silver, in “Education, Not Income, Predicted Who Would Vote For Trump,” pointed out that, in the 50 counties with the highest percentage of college grads, Clinton improved on Obama’s performance in 48 and won the great majority outright. In the 50 counties with the lowest percentage of college grads, she did abysmally - worse than Obama in 47 cases. In contrast, income was a poor predictor of Clinton’s performance. In well-educated, middle-income counties, she did just fine.

-

The bigger the city, the more likely it was to vote for Clinton. Smaller towns and rural areas went overwhelmingly for Trump, as this NPR analysis shows:

- Multiple studies support this view of the typical Trump supporter. For example, one analysis found:

mixed evidence that economic distress has motivated Trump support. His supporters are less educated and more likely to work in blue collar occupations, but they earn relatively high household incomes and are no less likely to be unemployed or exposed to competition through trade or immigration. On the other hand, living in racially isolated communities with worse health outcomes, lower social mobility, less social capital, greater reliance on social security income and less reliance on capital income, predicts higher levels of Trump support.

I could go on, but you see my point. To use Margalit’s terminology, economic insecurity is a factor of outcome significance - it’s why Trump won three key states and thus the presidency. Cultural insecurity offers more explanatory significance. Clinton, with her talk of deplorables, made it clear she didn’t understand cultural insecurity. Trump did, and that’s why people voted for him. Biden’s admirers think he also gets it, and that’s plausibly why in 2020 he got the presidency back.

Economic insecurity and cultural insecurity aren’t mutually exclusive arguments. On the contrary, you need to understand both to fully grasp what happened - that seems like the surest way of avoiding Trump 2.0. I gave inadequate attention to this distinction in the OP, and hope I’ve now put the matter right.