I don’t have any particular interpretive opinion on the tile in the OP, but I’d like to offer some background information and historical context that might be useful in how to think about it.

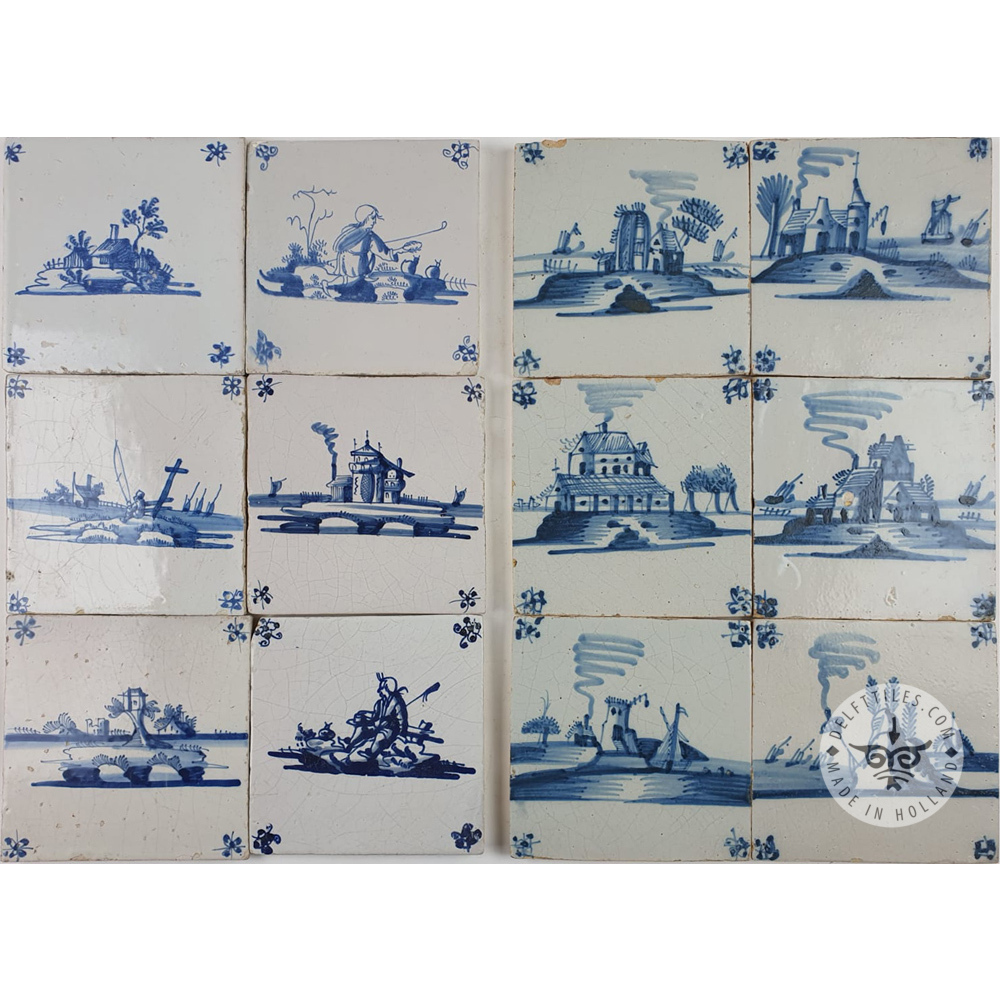

First I’ll amplify and expand on some points made by others previously. This does look like a distant cousin of a Delft tile. Tiles produced in the Dutch city of Delft (starting in the early 1600s) were certainly in demand, and they established a style that stayed in fashion for a couple of hundred years. But not every tile produced in this style is from Delft; there were many, many, many imitators capitalizing on the trend, to the point that “delft tile” is broadly understood to mean this kind of tile without any specific claim on the city of origin, or even just the Netherlands. The kind of calcium-rich clay they used locally allowed the production of very fine porcelain, but there were plenty of knockoffs elsewhere to meet the demand.

And it’s important to realize that there were a lot of these tiles made over the decades. Hundreds of millions, certainly — and multiples of that figure if you include all the imitators. If you tour enough period buildings in the region, you start to get a sense of the scale. I’ve seen walls decorated with this kind of tile everywhere from Portugal to Prague. The best-quality tiles (and Delft porcelain generally) were a status symbol, imported and installed in buildings both public and private.

But you’ll find these kinds of tiles — most likely not Delft, but, again, imitators — in more humble settings as well. For example, north of Copenhagen is a wonderful and fascinating open-air museum called the Frilandsmuseet where they’ve rescued a number of farmhouses and barns and other period buildings from all over Denmark, relocating and restoring and collecting them here in a sort of simulated community. It’s one of those “feel like you’re traveling backward in time” places, and it’s truly remarkable, highly recommended. This flickr gallery gives you an excellent feel for the place.

Most of the buildings are open and accessible, so you get to see how the rooms were laid out, how low the ceilings were, how they didn’t have bedrooms but rather these little raised alcoves just big enough for a mattress, and so on. And in many of the interiors, you will find these accent tiles, all original to the period, showing exactly how they were used as decorative accents by people of the time. And that’s the most important thing to understand: these tiles were not used as individual artworks; each is simply one of many in a bigger installation. In some places you might cover a single wall; elsewhere you might have a border row edging the ceiling or under a window or around a hearth.

This other flickr gallery has some close-ups from around the Frilandsmuseet, including some of the period porcelain on display the way the original residents would have had it. About halfway down the gallery, there is this picture:

Couple things to note here: First, observe again that there isn’t one tile on display, there’s a bunch covering the wall; the point is not the subject of any one painting, but the entire collective visual of many tiles together. Second, more importantly, note the tiles aren’t entirely unique; the kneeling figure appears twice, with basically the same composition, though the details vary. It makes sense if you think about it: these things were mass-produced on a staggering scale for a pre-industrial society. If millions are being made a year, you can’t possibly come up with an original subject every time. Top artisans might be responsible for the highest-end tiles to be installed in some wealthy merchant’s parlor, but millions more tiles were painted by low-paid craftspeople at all levels of quality, basically repeating the same basic designs over and over and over, morning until night, as quickly as possible.

There would need to be some variety, of course, so customers would have options from which to choose; say, every few weeks, the workshop would switch from “woman picking flowers” to “man outside church” to “dog running” to “small house” to “hunter with bow” to “ship docked at pier” and on and on and on. Each various subject didn’t have to be particularly inspired; you just needed a whole lot of them. When you stand and look at an installation of these, one at a time, you see the subjects are generally quite prosaic, and, as mentioned by others previously, painted in a fairly rudimentary primitivist style. The point, again, is not fidelity to life, but industrial volume. And if you’re looking for new ideas, why not check out the workshop around the corner and rip off their designs? They’re doing the same for your output.

This connects to the very similar tile featured on that page found by Joey_P (I agree, very good sleuthing). It’s safe to say there were many, many thousands of this cow tile produced, by probably dozens of artisans across multiple workshops, copying one another and laboring endlessly on the same repetitive design, until it was time to move on to the next one. Under these conditions, it makes sense that the individual tile doesn’t really stand up to much scrutiny. It was probably the thousandth tile painted by its artist in the middle of several weeks of output, basically on autopilot, possibly copied thirdhand from some other workshop’s original concept in a game of artistic telephone. Whatever the originally intended design might have been, it’s no doubt suffered through repetition and boredom, the ships being reduced to near abstraction, the cow rendered as simply and crudely as the workshop’s master would tolerate.

To be clear, I’m not trying to take away from the interest or value inherent in the tile, by claiming it’s a meaningless piece of mass production. Just the opposite — I’m trying to argue that there is tremendous interest here, just not of the originally considered nature. This came from a person’s hand, working in what we would consider today to be unspeakable conditions, very similar to the third-world sweatshops we don’t like to remember are still making our clothes and other consumer goods even now. Imagine the individual laborer who painted this, and imagine the whole chain of influence and logistics — fashion spreading across borders, import-export moving shiploads of these tiles from Dutch ports and wagonloads from Dutch cities, Polish and Portuguese entrepreneurs seeing these objects and setting up their own workshops to exploit the increasing demand, Danish farmers dropping a handful of hard-earned coppers at a local market to dress up their otherwise dark living spaces — that resulted in this singular object finding its way to your hand, decades and decades later.

It’s a very, very neat thing. I just don’t know how much mileage it’s possible to get in trying to figure out what the artist meant by painting it.