I do sympathize with those who struggle to fit exercise into a busy schedule. It can be hard to do. Kudos to you for doing some on a consistent basis. Maybe only 15-25% of people do. It may not be that easy, but worthwhile things rarely are. But if exercise worsens asthma or wakes you up at night consider talking to your doctor about better controlling it.

That is a work in progress! I’ll be seeing someone for follow-up on September 12. It only happens when I get sick, the problem is, with a small child, I get sick a lot. However I was able to do three sets of overhead press today without any problem so this is a good strategy especially for getting through the sick and asthma days.

I’m currently brainstorming ways I can fit more exercise in throughout the day rather than making it an Event.

If anybody has any short interval workouts to recommend, I’d be interested. I have found on You Tube that workouts labeled HIIT are often not. They are just sustained high intensity which doesn’t help me really.

I heartily endorse your brainstorming efforts. Coincidentally this came up in my news feed today:

Biggest point how the all or nothing attitude gets in the way. This article suggests 10 minute exercise breaks, and highlights the mental health benefits.

Meanwhile to your second question:

But again it does not even need to be ten minutes at a crack. Even two minutes here and there add up to real benefits.

Glad your tendinitis is apparently finally improved btw. And hope your child’s service plan is working great!

Thank you! We just got back from the meet and greet with his teachers. He loved every minute of it and didn’t want to go home. He starts school tomorrow!

This seems like a good thread to discuss the schism in bodybuilding thought regarding muscle hypertrophy.

(First, an aside. I feel pretentious referring to “bodybuilding”, but the reason I use the term is to distinguish it from weight lifting. Weight lifters are concerned with how much weight they lift. Bodybuilders care about the aesthetics of their physique; the weights are just a means to an end)

Anyway, the issue comes down to a question of frequency and volume.

Old school bodybuilders used to train for hours a day, and when they did their workouts they would do dozens of sets, over several exercises, for each body part. The thinking was that you wanted to hit the muscle from every angle, and the goal was to get as much of a “pump” (i.e. blood flow in the muscle) as possible.

So, for example, if training chest you might want to do flat bench press, incline bench press, dumbbell press, flies, dips, cable crossovers, and pullovers.

There is another strategy, however. It’s sometimes called “heavy duty” training, but it works on the principle that muscles are stimulated by a stress, then recover during rest, so workouts should be of extremely high intensity and very brief.

Taken to extremes, it argues for literally doing one set of an exercise for each body part, to absolute muscle failure, and that’s it. Then rest a week and do it again.

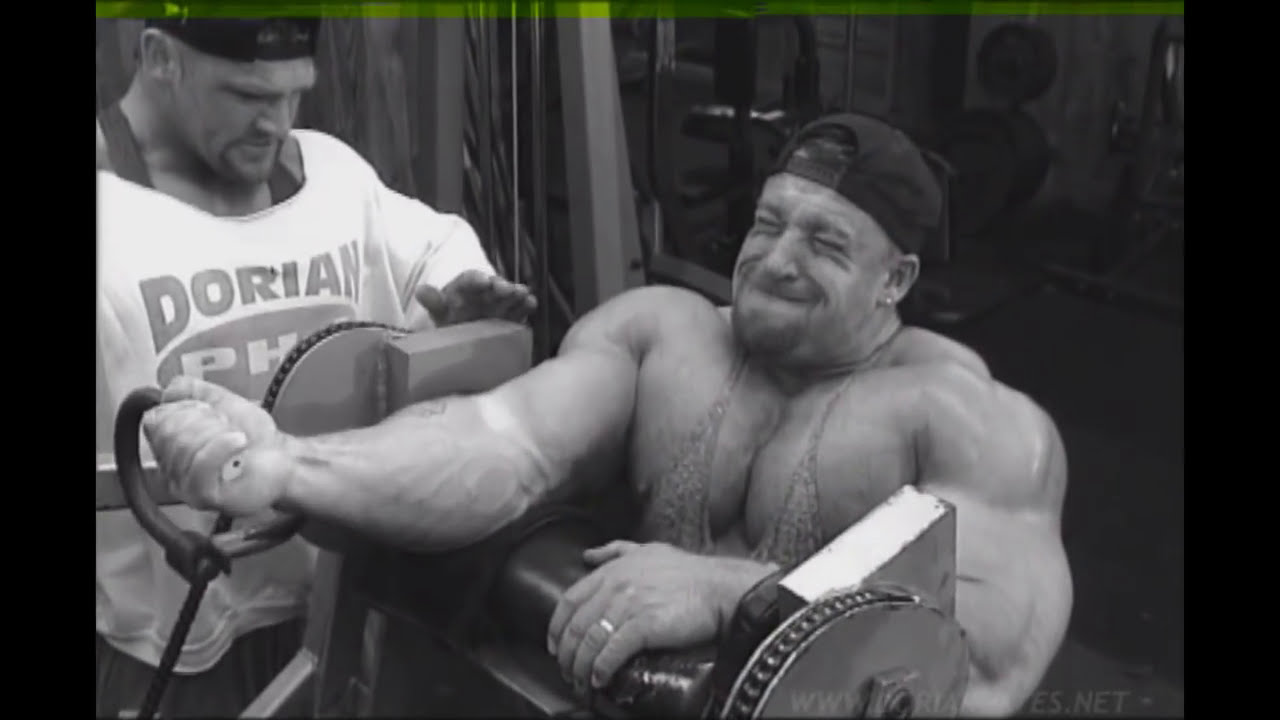

This idea was first promoted by Arthur Jones (who invented Nautlius equipment), is often credited to bodybuilder Mike Mentzer, and was used to great success by champion bodybuilder Dorian Yates.

The advantage of this technique is that it means you are having short workouts (maybe 30 minutes, including rest), solving the problem most people have of not being able to devote 4-5 hours a day in the gym.

The disadvantage is that it is incredibly taxing. Absolute muscle failure is more than just not being able to do a concentric rep - it means not being able to even hold the weight, after you’ve exhausted even the eccentric and isometric portions of the lift. And that can invite injury, to say nothing of the mental toll.

Nevertheless, this theorizing has been hugely influential on training, and does come from a scientific approach: if exercise is a stimulus for muscle development, you should only do as much as necessary to achieve that stimulus, and no more. Then focus on recovery.

For me, it translates into some principles that I apply. My workouts are always less than an hour, and I shoot for high intensity. I nearly always start with a basic compound lift (such as bench press, squats, or barbell rows), and after a warmup focus on going (in Dorian Yates’ words) “balls in” on just a few work sets. But I train alone, without a spotter, so I’m not actually going to total muscle failure. And, with my body half way through my 45th year, I have to be very careful about injury (muscle strains put such a damper on progress).

But I also add in a few other exercises to seek out the pump. I may only do a few moves (3 for chest or back, or 2 for something like biceps or shoulders), and I don’t try to hit every possible angle, but I’m not sure there isn’t benefit from trying to flush the muscles and make them as full as possible (at the very least, it’s fun to do).

The old school high volume philosophy is sometimes derided on the basis that those guys used steroids, and so would grow regardless of what they did, and that a natural trainee would be subject to overtraining. However, those guys who now talk about what PEDs they used will say that they only used them close to contests - I suspect the body can handle higher volume amounts.

Similarly, I’m not totally convinced that trying to complete every possible rep of a set is always a good thing. I’m guessing that it might trigger the type of cortisol response to stress that actually is counterproductive.

Regardless, it’s an interesting debate (not least because Mike Mentzer - a heavy duty guy- was extremely bitter about losing the 1980 Mr Olympia contest to one Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Schwarzenegger was a prototypical example of a high volume guy. So Mentzer (who died in the 1990s) was eager to denigrate the high volume approach. And when Dorian Yates won the Olympia with Mentzer’s help, it seemed to validate his ideas.

The arguments continue today.

(And if you are curious about what high intensity means, Yates was pretty famous for his workouts in his dungeon, which he calls Blood and Guts training. Here’s a clip. Now, you should know that Yates is British, as is his training partner. And it’s the partner (an amazing and very kind man) who is doing all the yelling. It’s meant to be inspiring, but it is jarring if not expected)

The thing about weightlifting sites is that their business model involves writing things frequently. Though they have a lot of good information, there is also a lot of chaff and some of these supposed controversies are storms in teacups.

The fitness community is small. I’m not sure what exactly motivates people to piss on things they don’t personally do, say CrossFit or Zumba, or insist there is only one way to do something, or one way best for everybody. And then just that, all the time. This leads to many stupid arguments, some of which are fairly settled in the decade or two meathead logic has had some degree of scientific study and experiment, often by scientists who love lifting. Even the differences between powerlifting for strength and pure aesthetics are not as big as often presented. Most Americans get twice the recommended levels of protein and don’t look like they exercise much but people are obsessed with a minimal intake. Why? (I don’t deny the minimums are in need of revision for some populations. But most lifters get enough protein if they enjoy meat and eat it often in quantity. Is it “optimal”? The idea of “optimal” is given too much emphasis by lifters. There is a degree of individual variation, some uncertainty, the goal is relevant, and it is stupid to be more certain than current evidence warrants.)

Of course people have different goals, and these may change over time. Although a surprising amount of meathead ideas are true, many are false. People who compete have very little incentive to be honest about using steroids despite the long term harms they clearly cause. Some older lifters predate the availability of supplements, but not all advice is very useful for those who only lift naturally.

If you are an athlete in a sport divided by weight class you want strength without size. Most lifters want both, with varying degrees of aesthetics, some of which are not possible for most natural lifters. Strength and size tend to work together, though if your lifts are all below 60%, strength gains won’t be as rapid, which tends to require efforts over 85%. But you can still get plenty strong.

To those in their first year of lifting, quick growth in strength and size is available for anyone who puts in incremental work, eats well and pushes themself even with rudimentary knowledge. After a few years more strategy is required. The best advice is still to switch focus and modify routines every 4-8 weeks. It is wise to try different things and see how you, as an individual, respond. You want to do the things you enjoy which work, as long as they do, while doing enough things to improve weaker areas. Often, doing something close to the opposite of what you have recently been doing stimulates growth once at a certain level.

The idea X body part requires lifting Y times a week is simplistic and does not use the latest science or real life demands. If you can only lift once a week it makes sense to work major groups and constraints may involve only one difficult lift for each group. Nothing wrong with that. Yes, you can still grow if things are properly planned. Working until you can’t makes recovery more difficult. You might want to save it for a few muscle groups. I don’t think you need to do it very often to achieve the goals of most lifters.

Knowing growth is stimulated by different systems, what makes more sense than doing one arduous set is using some of the same ideas to activate these different systems, without making recovery more difficult by overstimulating muscle. For example, using bodyweight dips, do 3 sets where one does 5 dips at normal speed, 5 dips with a 5 second descent, 10 more dips at normal speed, then one dip with a long hold at the bottom, ideally 15-30 seconds; repeating this 3 times. It hits all the sweet spots for growth. Lactate, mTor, volume; adding weight can be done but isn’t necessary. You could also add a set as quickly as possible while maintaining form. You’ll still be able to move once you do it. But after 4-8 weeks time to do something different; you stop making progress when you get too used to any one thing which is why the volume debate is stupid in the first place - do both plus the middle ground.

Another example is benching say 90% for 3 lifts, doing 5-15 lifts at 60% (until difficult but not impossible, generally leaving 1-2 in the tank), then a bunch of fast ballistic lifts at 20-30%. Hits strength, hypertrophy, volume and speed-strength parts of the curve. Worth doing for a few weeks, but then change stimuli so your body doesn’t get too good at one thing. You could lift maximal effort for one set until fatigued or maximize volume, both of which can delay recovery, but if you always use the same approach than you are not challenging yourself wisely. Of course goals influence actions to some degree, less than is usually claimed, but people mostly have similar overlapping goals wanting some degree of strength and also looking powerful, with other benefits in health, fitness and longevity.

No expertise but ISTM that the fact that multiple approaches have each produced champions is good evidence that none are clearly superior?

Maybe individual genetics and more matters too.

I love this suggestion. Thank you! When I was a teenager I tried a workout based on doing sets super slow (like 5 second concentric and 10 seconds on the negative), and I recall quite the burn. Switching up tempo within the set is brilliant!

The bros have applied the term “progressive overload” to the mechanism for muscle growth. Usually, that’s accomplished through the use of heavier weight, or doing the same weight for more reps. But there’s a lot of talk about “time under tension”, and you can also reach that goal with slower reps.

See, I’ve done the “burnout” set, where you drop the weight and try to get more reps, but I’ve never thought of doing fast light reps.

Some recent training information I’ve read related to power movements, and your suggestion would seem to incorporate that. Whereas my inclination is to slow down my reps, I like the idea of ballistic movements.

Oh, I absolutely agree. The basic concept is consistent - stress muscles to make them stronger - but there are clearly many forms of stress that will create that metabolic response.

I’ve read a suggestion that people will naturally train according to the type of muscle fibers that are most dominant. That is, if you have more slow twitch (endurance) muscle fiber, you will be inclined to do higher rep sets. But if you have more fast twitch (power) muscle fiber, you will be inclined to do heavier, lower rep sets.

It’s fine to increase load. But you eventually hit plateaux. Now what? Can’t increase the weight, or often even lift what you did last week. But you can decrease rest time, increase volume (sets or reps), introduce pauses, slow things down, change exercise order to pre-fatigue muscles, do supersets, increase density (improve upon X lifts in time Y), try “every minute on the minute” (well worth trying, do 5-15 seconds of work, rest 45-55 seconds, repeat with the same weight at 60-80% again and again), change grip and range of motion, do variations, etc.

But remember the basics: force is mass times acceleration; power is force times velocity. So increasing velocity (and power) by lifting fast (accelerating) is another option for increasing force (called speed work if light, or strength-speed if a little heavier). Strength-speed can be done using 20-30% of weight, going for speed with fairly decent form, and going for speed or jump height rather than significant weight. Jump squats (with a trap bar) work very well, as does throwing a light weight skywards repeatedly on the Smith machine and catching it (this has always worked for me but apparently some Smith machines have a counterweight which slows things down too much, never seen this). For presses, start light, go to 20-30%, emphasize speed. (I have gone above 60% but experts I trust says this will be too slow to achieve the benefits; still seemed fast to me, but the idea is to stop increasing if you slow down at all). The Westside guys devote a whole day to lifting light weights fast, often 20-50%. As you surmise this works power.

FWIW my second suggestion with benching is called a “cluster set”. For more details on different force curves and dozens of other fine tips rarely seen elsewhere, and some academic research too, see Thibaudeau’s excellent “Black Book of Lifting”.

To some degree, training can change your muscle fibre ratio somewhat. The idea of lifting above 85% for strength is to recruit all the IIb fibres.

I’m thinking that this is one reason it is so hard to read literature and get real answers. Responses to different interventions are doing to vary based on past training (amount and type), selection of subjects by age and built in predispositions to respond in different ways. A study of how competitive cyclists respond to a specific exercise intervention may or may not translate to football linemen, or a soccer player, or a wrestler, or a body builder, or some group of middle age women …

Most of us (maybe not the two of you!) though are at levels where the fine points don’t matter much, fortunately! We just need to be doing something for strength training and ideally do it in ways that are fun enough that we stick with the habit.

So for about two weeks I’ve been doing a small amount of strength training every day (alternating muscle groups, abs, legs, arms, with one rest day every three days.) Just two exercises, usually three sets each. I’m talking less than ten minutes of work per day. I do it while my son is brushing his teeth.

Do I feel better already? Yes. Today I just realized that my near-constant complaints of “I’m old” have ceased.

Hard to believe something that simple could make that much of a difference.

This is awesome! I’m truly, genuinely excited for you! In my mind, this is called “proof of concept”: you’ll never need to doubt whether you, personally have the will, strength, or mental toughness to improve and transform your body.

(Hopefully you even enjoy it a little bit, too! It’s fun to get all sweaty and taut, right? You might even try snarling in the mirror: go on with your bad self!)

Again, way to go!

The best answers come from people who have a good reputation for training athletes in many different sports, follow academic research, know the meathead science and can interpret studies, are experienced lifters but also do other forms of exercise themselves, and understand nutrition. I could name maybe ten such people.

Although a few such people exist, most people do not need fine points or much theory. They need to move regularly in some way that produces motivating visible results or is otherwise enjoyable enough that it can be sustained.

I enjoy the theory. But it is easy to get bogged down in it. Discussing theory is not at all the same thing as concrete action.

It really is pretty amazing isn’t it?

![]()

I’d suggest looking up Mike Israetel / RP Fitness on YouTube, if you really want to go through the science of bodybuilding.

But the real answer is that pretty much any technique variation is so vastly outweighed by things like consistency, diet, total volume, recovery enhancement (e.g. rest days, block training, and PEDs)°, and hormones (e.g. genetics and PEDs)° that you can basically find dudes of any mass of any scientifically perfect or downright dumb technique in the actual gym.

There certainly are things that seem more scientifically and logically supported but they don’t matter too much.

As best I’m aware, the only thing you can do to differentiate between bodybuilding and strength training is to use more reps at lower weights, and to use more muscle-specific targeted exercises. Training to failure doesn’t seem to be necessary but it can keep you from cheating too much but, so long as you get enough volume, that doesn’t really matter. Massive dudes cheat constantly and get the job done. Other massive dudes go to failure and focus on their technique. They’re equally massive. The important thing was they came to the gym and processed a sufficient volume in totality.

° Not an endorsement of PEDs, just giving my understanding of the state of the research.

The main reason regularly training to exhaustion is not a good idea is that it can easily affect future workouts for relatively little benefit, but significantly impede progress, especially if there is increased risk of injury. However, overtraining and central nervous system exhaustion do not mean what most people think they do.

Variations in technique matter, but not to the average gym-goer who just wants to get in somewhat better shape. Technique is very important in Olympic lifting and very relevant to avoiding chronic injury, such as shoulder injuries caused by years of bench pressing. But there are other relevant things some of which compensate for mediocre knowledge. A beginning lifter will grow substantially just by showing up and making a conscious effort to increase work when possible.

You can increase muscle size without increasing strength. You can increase strength without gaining weight. Someone only interested in aesthetics is more likely to pay more attention to dietary factors even if they limit workload or energy levels. Someone only interested in powerlifting or Olympic lifts is essentially only interested in improving what lifts are relevant for competition and improving those by doing variations of essential lifts. There is more to these differences than just exercise selection and set-rep-%1RM, but these are also important as are the other modalities mentioned. Events divided by weight class offer an incentive not to merely gain size.

There are a lot of natural differences in technique and limited debate over issues like full vs partial range of motion, appropriate assistance exercises, speed-strength work, gear and many other things. However, recent research has led to many surprising conclusions about these things.

Recovery has become big business but the basics of time and rest still account for most of it.

Can you clarify what most people think it means compared to what it does mean? I’m not sure that I know myself.

I always understood that the basic approach, whether training at a relatively heavy or light load, was to lift a number of rep such that the last rep was the last one that could be done maintaining “perfect” form. (With some advanced lifters allowing some imperfections or, as you do, partial lifts.) That “lifting to failure” means lifting to where the next rep would fail that standard.

Of course in gym, with spotters, back when I did that, I see the traditional spotter yelling to go to the last rep literally failing, them helping rerack as it fails. That seems like little additional gain compared to possible harms and more of a social thing! But who am I to say? These are usually guys much bigger and stronger than I am!

The approach that I understand has the advantage of not ever really needing to test 1RM. Just lift to that point, adjusting weight to keep that point in your target rep range. Whatever that is and best to mix it up ever so often, whether seriously done with official periodization, or more casually to keep things novel and fun.

As to your first point, IF allowing for adequate recovery (more recovery for overall harder more muscle damage greater stress workouts) and perfect (enough) form is maintained then does your concern apply?

The main problem with imperfect form isn’t that it doesn’t help growth. It is that it increases the risk of injury, and does not lead to maximal growth over the parts of the range of motion not included (if never worked, especially tendons and ligaments which also need to grow to avoid injury with heavier weights). Imperfect form has a place if done consciously and strategically.

In fact, a lot of muscle can be built using partial ranges of motion. Strength is gained by intelligently pushing ones limits, which often leads to imperfect form. I personally think imperfect form and partial ranges of motion to be very valuable for experienced lifters, more at the end of a workout, after using better form and range of motion for the initial sets, provided the deviations are small enough to keep injury risk very low.

The main issue wth fatigue is that not all the muscles or movements are equivalent. For a casual lifter, lifting twice a week and doing ample cardio is reasonable if one increases recovery times from heavy cardio which can sometimes be hard(er) on the nervous system (than even a heavy weight workout). But the science is more nuanced.

Muscle fatigue is simply doing enough that you can’t maintain the required force. It doesn’t happen all at once; the movement slows down before it can no longer be done. But the nervous system, depleted of acetylcholine and dopamine, controls the nervous system which controls the muscles, can take over six times as long to recover, and recruits the muscle and controls its firing rates and coordination. So it is the boss. You are not just working muscles but important things like tendons, ligaments and nerves.

Most exercise physiologists believe recruiting a muscle fibre is not enough to stimulate growth: it needs to be fatigued and maximum growth requires causing the most damage by fully exhausting it. To recruit all the muscle fibres, including the type 2b ones for strength, you need loads that are over 85% of one’s current ability (which changes throughout the set; the more you do the lower your 1RM in the present moment).. But this damage increases the amount of recovery time required. So there was debate about the balance between maximum stimulation and damage versus the additional recovery required.

But there is a simple solution, (according to Thibaudeau) because different types of exercises have different effects on the nervous system. The principle is the more strenuous and exercise is on the nervous system, the earlier you stop it before exhaustion.

Olympic lifts and fast ballistic movements are toughest on the nervous system and should be stopped as soon as the movement slows down.

Tough exercises: deadlifts, squats and presses, etc. are tough on the nervous system and should be stopped one to two reps short of failure, with some speed loss acceptable.

Isolation work on chest, quads, hamstrings, core, abdomen or lower back - especially with machines - is lower nervous stress and can be done to exhaustion. You should go to exhaustion on at least one set or even all of them to maximize muscle growth.

Isolating small muscles like biceps, triceps, trapezius, lats, calves or forearms leads to little fatigue. You could use methods like pauses or dropping weights on at least one set, which allow the lifter to go beyond failure. Since these exercises are not demanding on the nervous system, these muscles can generally be worked very often without much impeding recovery.

Novice lifters often just work the arms since they think this will give them big arms. They get more growth from doing mostly multijoint exercises which work a high percentage of body muscle with just a little bit of focus on the arms (if any).

When I start trying to delve into the science of strength training for specific goals I appreciate that there are sound theoretical explanations for what experts like Thinaudeau proscribe, and that there are many who have followed those guidelines to achieve their goals and beyond. It sounds like it makes sense and I certainly cannot argue against any of it. But then I try to parse out the evidence based reviews and dang the evidence is all over the place. For example this one. One can cherry pick studies to support many different approaches …

Fortunately for me at my level and my goals (and likely most others on this board) optimizing strength or hypertrophy is of little importance. (Although I am curious to get your thoughts on my specifics. No need to clutter the thread with it though. I’ll message later and feel free to ignore.) But it is maddening.

Fortunately for me at the level that I advise, child to young adults who are beginning strength training, there are only a few messages that are most important for me to push. At their level the messages are every rep a perfect rep and respect recovery. It is also an opportunity to promote nutrition with the spin of optimizing their gains (quality parts for the quality sports machine they are working so hard to build).

Also, what did you mean by “recovery has become big business”?

Ach. You apparently are not private messagable.

Spoilered so others don’t need to bother with my exercise details.

Summary

So once to twice a week I strength train. In good weather I start with the rings (only enough room in the yard). Dips to failure (about 15) 3 sets, pull ups to failure varying palm positions three to four sets (about 15). In between pistol squats using the straps for partial support about ten each leg. Cats cradle to inverted hang to inverted pull ups (five) to attempted progression to rear flag to el hang. And several more brief el holds from up position. Inside to wall supported handstand push ups to near failure (7) and then a mish mosh with balance ball dumbbells of a variety of exercise balance disc static holds like planks of different sorts wall sits, but no single one of too many sets. Very little to none single joint work. Short rests.

From your guidelines I probably shouldn’t be doing the rings work to failure?

Otherwise it’s cardio (also a mix, cycling to work when schedule and weather permit, 45 min good clip each way, running with the dogs, elliptical, rower) trying to respect no two very intense days on top of each other.