AMSL It’s almost an hour but fascinating engineering.

That video is almost an hour long. Could you possibly break it down and give us a few highlights?

I watched the whole thing a few days ago and it’s really quite incredible. Worth the hour watch.

It’s that long because of the different pieces of crazy engineering that had to independently develop over decades with different labs competing and working with each other, and then all of it coming together inside an even more amazing package to make modern chips possible.

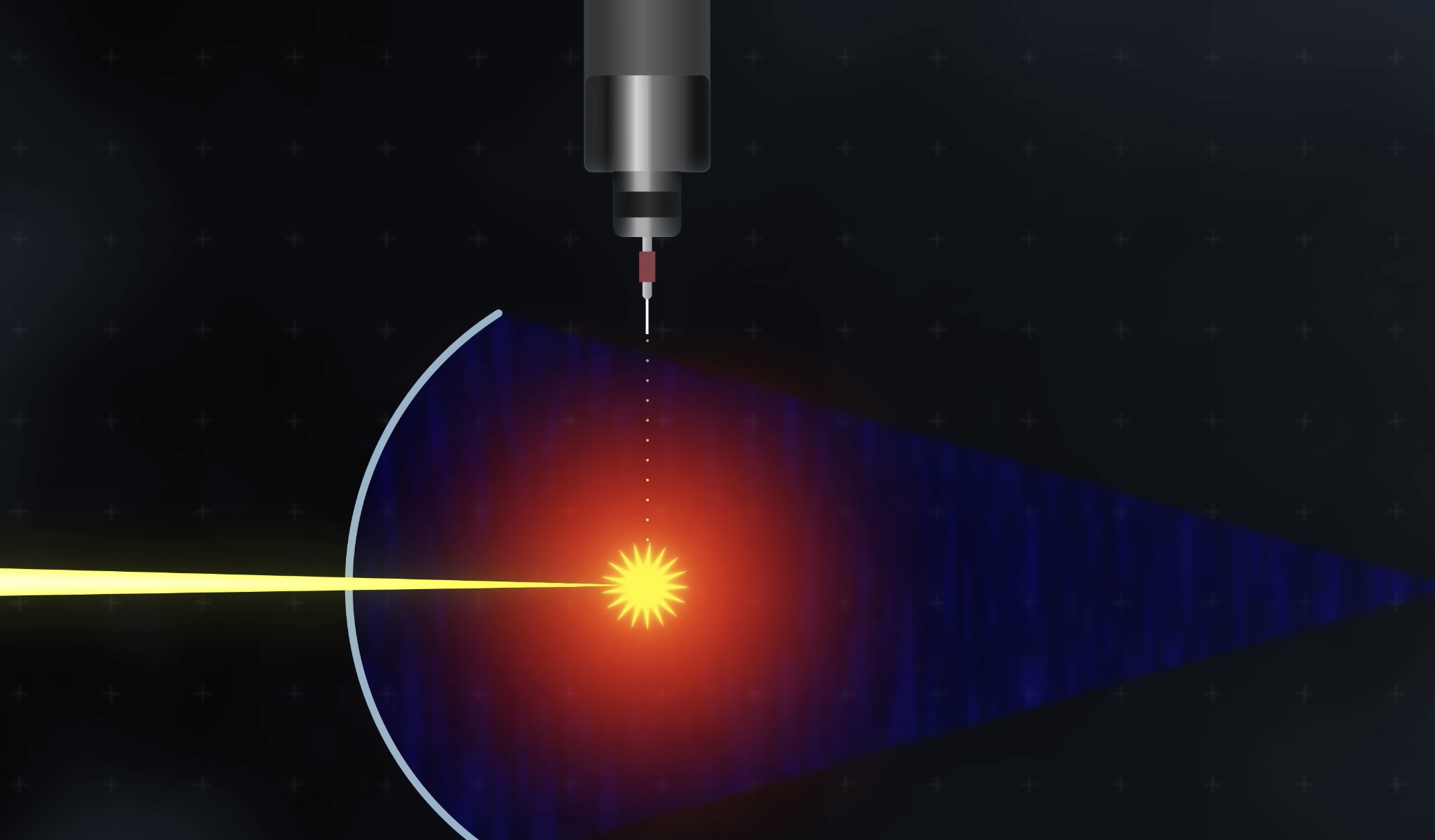

It combines an array of atomically ultra-smooth mirrors with lasers to blast a tiny stream of tin droplets thousands of times a second, hitting each droplet several times, first to flatten it a bit, then to smooth it out even more for better dispersion, and then the final pulse explodes the tin pancake into a tiny ball of plasma. The plasma emits extremely short wavelength ultraviolet light, which is necessary for creating the tiny nanometer-scale circuits on modern chips.

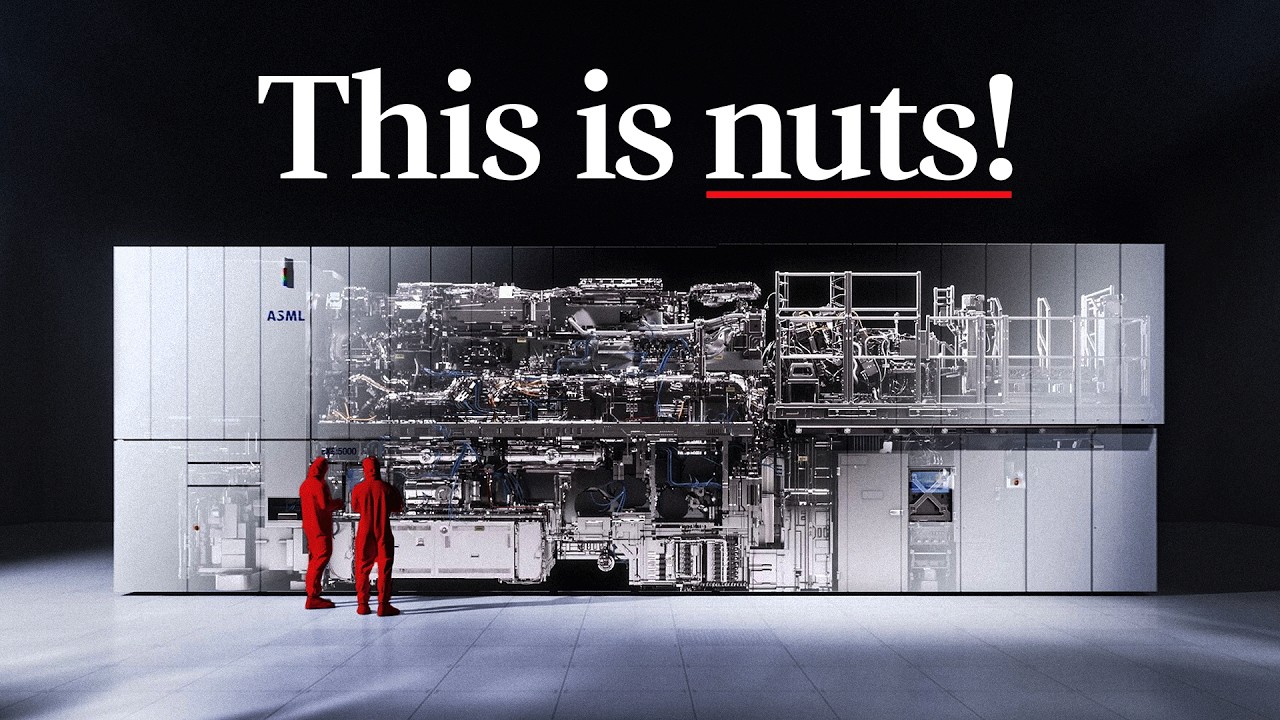

I don’t think the image and text really even begin to capture the full complexity of this sort of setup. It is among the most complex machines our species has ever made. The full video is worth making time for. It’s great storytelling that explains a fundamental part of modern life with great visualizations and interviews.

This video was suggested to me by YouTube’s algorithm the other day and I started to watch it but didn’t finish. If you prefer to read about it, the video is about extreme ultraviolet lithography and the Wikipedia article is here. The company that makes the machine is ASML Holding.

Yes, it showed up in my algorithm too, and I had it on while I was working on something else (something physical that didn’t require much mental attention). I kept interrupting my work to watch and listen more closely.

These machines are for sale, by the way, (ASML developed them for chipmakers) and they cost a few hundred million each, IIRC.

It’s a story of persistence and jaw-dropping engineering. A Japanese scientist first proposed this as a potential solution to the difficulties in making smaller and more powerful chips (back in the 90s, again IIRC), to almost universal disdain. A few other people picked up the idea, and spent something like 20 years butting their heads against almost impossible difficulties, until they had a breakthrough and not only made it work, but developed a path forward for even smaller and more powerful chips.

I haven’t watched the video but I’ve for years been fascinated by the technology. Those machines have to be the most high-tech, complex things ever built, and make a Saturn V or Starship look like Lincoln Logs in comparison. For example, photolithography needs a light source. In early chips, they used a (barely) visible light mercury lamp. For modern chips, just the “light bulb” is a 10 ton laser system.

What does the world’s largest industrial laser from TRUMPF have to do with the way we will communicate in the future? Quite a bit, as it turns out. The latest generation of computer chips would not exist without this giant laser, and nor would state-of-the-art smartphones. But first things first: It takes highly complex lithography equipment to produce the latest generation of microchips. Netherlands-based ASML is the only company that manufactures these systems, which work with EUV light. And TRUMPF’s colossal laser is the only device that can generate this EUV light. Weighing more than 10 metric tons, it consists of 450,000 individual parts. As the system’s light source, this laser generates plasma with a temperature of 220,000°C, which is 30 to 40 times hotter than temperatures on the surface of the sun. The giant laser is aimed at a stream of tin droplets inside the lithography system, where it strikes and flattens 50,000 of these tiny droplets every second. Actually, the giant laser takes two shots at each of these tin droplets, with the second hit transforming the flattened droplet into plasma that emits the precious EUV light. Of course, the laser’s light beam has to shaped in a very specific way to strike 50,000 individual droplets per second. The laser shoots compressed light packets at the tin droplets, which is why experts call it a pulsed laser. Each of the 50,000 pulses per second consists of a small, compact group of light particles, hurled at the droplets in a tight bunch. To hit their target properly, they have to arrive at precisely the right instant, not a moment too soon or too late; otherwise, the impact will not flatten the tin droplet. In the worst-case scenario, the second laser shot misses its mark so that the attempt to generate EUV light fails. And that brings us to Michael Kösters.

From here:

Which was a link from this thread

Also, the molten tin used in the laser system need to be some of the most highly refined metal ever produced: 99.9999% pure.

Later versions hit the tin droplet three times.

“Actually, the giant laser takes two shots at each of these tin droplets, with the second hit transforming the flattened droplet into plasma that emits the precious EUV light.”

I wonder how they came up with tin as the right element?

Sometimes it seems we have hardly started exploring possibilities of the periodic table yet… there may be marvels hiding there to be discovered! Room temperature superconductors, anyone?

What happens is that the laser kicks an electron up to a higher energy level, then it falls back down, emitting a photon with a wavelength (darn wave-particle duality!) of 13.5 nm. So it comes down to choosing an element with an electron shell configuration capable of producing light in a usable wavelength.

That is discussed in the video. You need an element that happens to produce the desired wavelength of light when ions of that element reabsorb electrons. They initially used xenon which produces the right wavelength but is very inefficient because it also produces more light at other wavelengths. They switched to tin because it also produces the right wavelength but the efficiency is 5 to 10 times higher than xenon.

Sure, I just haven’t had time to sit down and watch it yet. Fascinating stuff!

For ‘rising apes’ as the late great Terry Pratchett put it, we’re not doing too badly….

I think my neighbour has one of those machines parked in his driveway. He is a responsible guy, hence it sits on 4 bricks to keep it off the ground.

37 min if you speed it up to 1.5x

is your time not worth nothing?

How fast do you have to go to reach “Alvin and the Chipmunks”-type narration?

One of the engineers described the explosion of each tiny drop of tin plasma as physically very similar to a microscopic supernova. Fascinating stuff indeed!

For those who don’t want to watch the video the Wikipedia article linked in post #4 is quite informative, but the video goes into far more detail.

On the downside, this machine allows the manufacture of much denser and more powerful microchips which are then wasted in smartphones and in more powerful laptops where the tremendous hardware power is negated by increasingly enshittified software.

well, I assume you know that the pitch of the voices doesnt change in YT … I just raced through the whole vid in 34 min, being an Eng. as a 2nd lang. speaker … yep, my head hurts somewhat (I need to concentrate harder to follow at 1.5x) … but it is perfectly doable …

and as already mentioned a few times: well worth the time.

This is what happens if you bang rocks together.

I very much prefer to just watch a video at normal speed, but skip ahead once in a while through the more boring parts. More natural, and prevents headaches! ![]()

What happens if you bang rocks alone?