The Long Bust – Point 2: New technologies turn out to be a bust. They simply don’t bring the expected productivity increases or the big economic boosts.

“Technology which didn’t pan out as we hoped.” by Martini_Enfield

THE Jetsons has a lot to answer for.

A world of flying cars, robot butlers, and “work” that consists of occasionally pushing a button – all part and parcel with the 21st century.

Yet now, as we settle into the third decade of the decade which has symbolised “The Future” pretty much since the invention of science fiction, we’re still missing quite a few of the keystone items that we collectively decided would represent “The Future” as a concept.

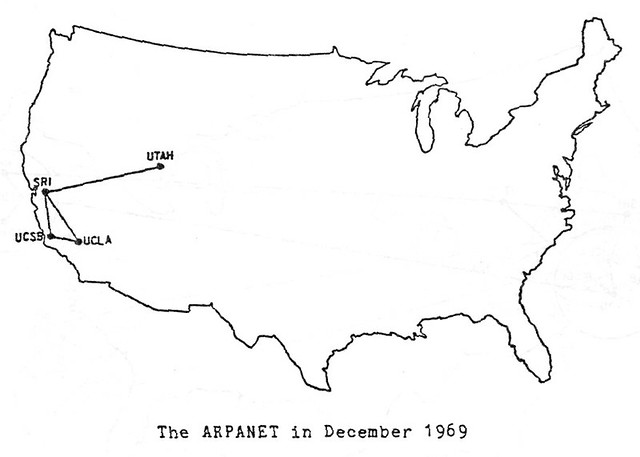

It’s been 25 years since The Long Boom was published in Wired magazine we certainly have our share of technological marvels nowadays that seemed like science fiction at the time that feature was written – advanced smartphones, the modern internet, drones, cars with well developed semi-autonomous driving capabilities – but that also doesn’t change the fact there’s a lot of tech we collectively expect to have by now and don’t.

Without further ado, here are a few examples of future technology which simply haven’t panned out the way we were hoping:

Flying Cars

I’m starting with the obvious one here – flying cars are tech that didn’t (and probably won’t, at least anytime soon) pan out.

Whether it’s the Jetsons and their UFO-inspired jetcar, the DeLorean from Back To The Future , or the ‘spinner’ vehicles from Blade Runner , “Flying Cars” have become inexorably entwined with our collective concept of “The Future” and the lack of flying cars in our everyday lives is frequently trotted out as a memetic theme about how collectively disappointed we all are in the way The Future has turned out.

It’s such a common trope that it’s hard to pick a specific example, but they’re one of the first answers in this 2010 SDMB thread about ‘technology we should have by now but don’t’, there’s this entire thread from 2014 (which is itself a response to this Straight Dope column on the subject too), and the fact that I bet when you read the title of this piece, “Flying Cars” was the first (or one of the first) things that came to mind.

Every few years, someone claims they’re thiiiis close to producing a workable, viable “flying car” and every few years, we still note that none of us are flying to work in our car.

As this 2013 article from Popular Mechanics succinctly explains:

To make vehicles like you see in cartoons, we’d essentially be building small planes that look like cars, which are expensive, awkward to fly, and create a host of new legal issues to deal with. (Do all drivers now need a pilot’s license? And should drunk flying be a bigger crime than drunk driving?) Costs would be beyond astronomical.

That hasn’t stopped people from trying, of course, and there are cars which can turn into an aeroplane (once you attach wings and a tail etc), but that’s not the “Flying car” we’re all thinking of when bemoaning their absence.

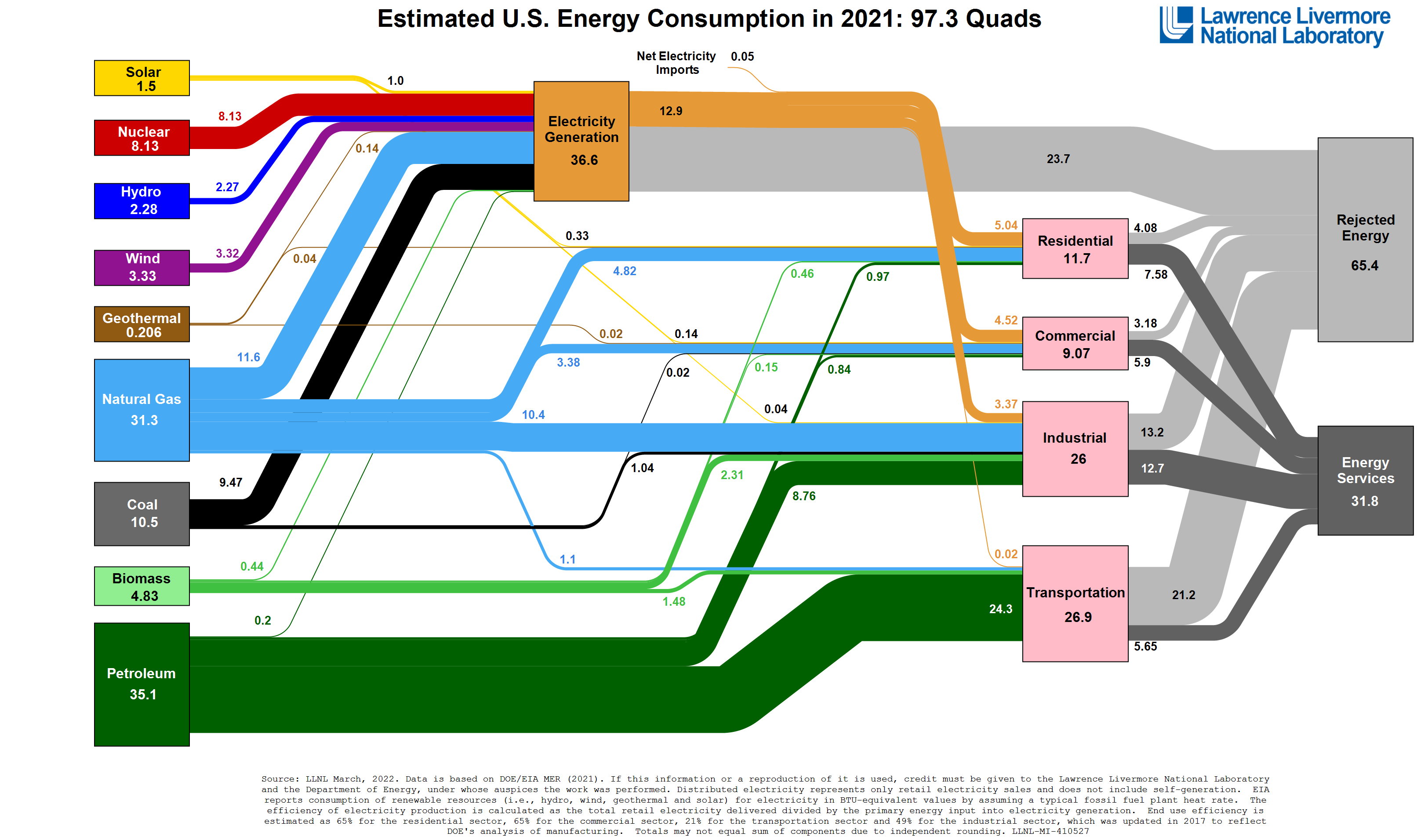

Automotive technology at the moment is based on replacing fossil fuel engines with alternative energy sources – batteries, in particular – so while I can’t complain about switching to a more ecologically friendly (and renewable) fuel source, that doesn’t mean I still can’t be miffed that I don’t get to cruise around in a flying car instead of having to drive everywhere while still earthbound like Fred Flintstone or something.

Laser Guns

It’s an iconic scene from one of the most iconic movies of the 1980s: A Terminator robot assassin from the future walks into a gun shop c.1985 and asks for “A phased plasma rifle in the 40 watt range”, to be met with “Hey, just what you see” from the sales assistant.

The same idea was revisited in 1993 film Demolition Man , when, a cryogenically frozen criminal escapes in the future and breaks into a museum to acquire weapons, and then asks himself: “Wait a minute. It’s the future. Where are all the phaser guns?”

I’m not even going to get into the assorted blaster weapons seen in the various Star Wars movies or the phasers from Star Trek , or video games, or… you get the idea. It’s the future. There should be laser guns. There aren’t.

Laser weapons have been around so long the term “1920s-style Death Ray” (in reference to the sort of guns that Buck Rodgers and other Pulp Sci-Fi Comic heroes wielded) even became a shorthand-slash-meme on the Straight Dope Message Board poking fun at “awesome but impractical or unrealistic” weapons and technology.

So how come you can’t buy a BL-44 Han Solo blaster pistol for personal defence?

The short version is energy requirements. The amount of energy needed to make an effective laser weapon is astronomical and there’s simply no feasible way to make a battery pack small and light enough be carried with the weapon.

As this 2018 article from The Guardian discusses, there are several promising developments in the field of (and some advanced prototypes of already in existence) laser weapons – but they’re all varieties of emplaced (or ship-mounted) laser and still not the “pew pew” laser weapon most people associate with the term (lasers fire a continuous beam rather than a bolt of energy, for starters).

While we will likely see directed energy weapons in action in the foreseeable future, they’re still not going to be like anything out of Star Wars , even if they are mounted on battleships or in fortifications, and it is still going to be quite a long time before any of us can go hunting with a Fallout -style laser rifles.

Supersonic Airliners

This is an usual example of an existing advanced technology commonly associated with The Future falling out of use and not being replaced with anything (yet).

The maiden flight of the Anglo-French Concorde supersonic airliner in 1969 heralded a new era of aviation, very much in keeping with the optimistic “Forward to THE FUTURE!” attitude of the era (which was, that same year, putting people on the moon for the first time).

Travelling at Mach 2 (2,158 km/h; 1,350mph), the Concorde could fly between London and New York in about three and a half hours – more than half the time of a conventional jetliner of the era. Aimed at wealthy travellers, the aircraft became a symbol of British (and French) technological progress, sophistication, and style.

The British and French weren’t the only ones to build a supersonic airliner either – the Soviets managed it, in the form of the Tupolev T-144, nicknamed “The Concordski” due to its obvious visual similarities to the Concorde (internally, however, as SDMB user engineer_comp_geek notes in this thread, the two aircraft were very different).

Sadly, it’s no longer possible to travel as a commercially at supersonic speeds - the Concorde was retired from service in 2003, while the TU-144 (which had a host of problems) was officially retired in 1999 but hadn’t been used for passenger or cargo flights - most of which were basically so the Soviet Union could claim to have a supersonic airliner in scheduled service - since about 1980.

As this story from Business Insider explains, the end of the Concorde era of supersonic passenger air travel ultimately came down to the Concorde being expensive to refuel and maintain – it reportedly needed nearly 22 hours of maintenance by a specialised, highly trained crew for every hour the plane spent in the air.

Even worse, the supersonic boom created by the aircraft crossing the sound barrier caused many countries to ban Concorde from flying over them, severely limiting the routes the plane could use and effectively meaning it was only viable on nearly entirely trans-oceanic routes like London-New York. Add to that its limited passenger capacity (around 100 passengers) and some high-profile accidents in later years, and the shine had well and truly worn off.

It’s nearly 20 years since Concorde’s last flight and as anyone who’s lamented being stuck in economy class on a long-haul flight has probably wondered how come no-one’s developed a “better” supersonic jetliner to replace Concorde.

The short version is the broad issues which undid Concorde still remain and there’s still plenty of work being done in developing practical supersonic jetliners , including by companies like Boeing, Airbus and Lockheed Martin . Much like flying cars, though, new supersonic airliners have been ‘just around the corner’ for decades, so at this point I’ll personally believe it when I see it (and hopefully get to fly aboard it).

3D/Holographic Movies

You know that scene in Back To The Future Part II where Marty McFly is outside a movie theatre and thinks he’s being attacked by a hologrammatic shark, but it turns out to be a promo for a new instalment in the Jaws franchise? That’s the sort of 3D Movie experience most of us were led to expect would exist in at least some capacity by now, and yet we continue to be disappointed.

3D Movies have been touted as “the next big thing” ever since 1952’s Bwana Devil ushered in the image of a theatre full of patrons wearing red-and-blue cellophane glasses to be accosted by lions appearing to jump out of the screen at them.

The concept remained a novelty for decades, until James Cameron’s 2009 blockbuster Avatar , which caused a sudden explosion of interest in 3D movies, leading to several more being made (either for 3D, or being ‘retrofitted’ in editing to become 3D).

The trend didn’t last however, and in many respects was over in a few years, with several factors being responsible.

In addition to the extra ticket cost and the need for glasses, the 3D effect wasn’t always especially well done – with several SDMB posters complaining in this thread from 2012 that ; an issue typified by user DCnDCs comment that “Instead of making it “more real,” to me the 3D has the opposite effect of making everything look fake, even when it’s just two guys standing in a room talking to each other. The image has layers, but it still has no depth; the layers may be separate from each other, but the image in each layer is still flat, which makes everything look like a cardboard cutout.”

Other posters called out the higher prices, the tendency to headaches while viewing, and general issues with visual quality.

3D movies are still being made ( Avatar 2 is coming out in December) and there are still plenty of cinemas in the US screening 3D movies, but for the most part audiences decided the 3D effects weren’t worth the extra money or dealing with the glasses and other (sometimes literal) headaches, and have turned their back on the concept.

It’s been the case internationally too - a cinema chain owner here in Australia told The Sydney Morning Herald in 2019 that all their theatres had 3D projectors, but they were mostly going unused – “ We dust them off and fire them up maybe once a year, just to make sure they still work,” he is quoted as saying.

As for holographic movies (think Princess Leia’s distress call via R2D2 in Star Wars) , we’re nowhere near that and probably won’t be for a long time – there’s simply too many technological barriers to overcome, as this 2017 article from NPR explains.

While 3D technology is rapidly becoming more practical, accessible and worthwhile for video games and other computing tasks, the idea of a 3D or hologram movie cinema experience seems destined to remain very much in the future.

Lunar Resorts

Rather a lot of us who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s were positively assured, via movies such as 2001: A Space Odyssey , TV shows, and books such as The Usborne Book Of The Future that by the 2020s we’d be taking our holidays at the Hilton Sea Of Tranquillity, hitting a few rounds of golf around the back nine of the Greg Norman Moon Club, or visiting some kind of lunar theme park (thanks, Futurama!) .

Not only has that not happened, there hasn’t even been a manned mission to the moon since 1972 – literally 50 years ago.

If you’d told 16 year old me back in 1997 that, in 2022, the Chinese and the Indians would have been the most recent nations to send uncrewed missions to the moon and the US hadn’t been back since a decade before I was even born, I’d have laughed at the funny joke you were making because no way that was true.

So what happened? The short version, according to the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum is that manned lunar landings are really expensive and the American public lost their enthusiasm for the whole thing with everything else going on at the time:

“For many citizens, beating the Soviet Union to the Moon ended the Space Race. Public support for expensive programs of human space exploration, never very high, declined considerably; enthusiasm was further eroded by the expense of the Vietnam War, the serious problems in the cities, and a growing sense of environmental crises.”

This wasn’t helped by it turning out there’s not actually much of interest up there on the Moon unless you like rocks (and those rocks are, geologically speaking, very similar to the ones we have on Earth)

We basically learned pretty much everything we could from wandering around on the moon fossicking for interesting rocks and have now turned our attention to Mars, where the actual science fiction stuff – remote-controlled rovers and helicopters exploring a different planet – is going on instead.

And that’s why I’m not writing this story from a Pan Am Space Clipper en route to a lunar resort.

Martini_Enfield